The Fermi–Dirac distribution gives the probability that a quantum state of a given energy is occupied by a fermion at any temperature above absolute zero, accounting for the Pauli exclusion principle.

It is essential for describing the behaviour of electrons in solids and underpins our understanding of electrical and thermal conductivity in metals and semiconductors. Because many modern technologies, such as transistors, lasers and integrated circuits, depend on the behaviour of electrons in materials, the Fermi–Dirac distribution is a foundational tool in both solid-state chemistry and electronic engineering.

To derive the Fermi-Dirac distribution, consider a system of fixed-volume containing electrons occupying discrete single-particle energy levels , each with degeneracy

. If

electrons occupy the

available states of energy, where

, then the total number of electrons

and the total energy

of the system are

where

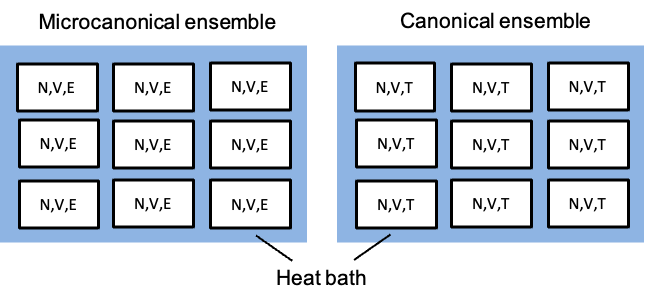

Replicas of this system form a microcanonical ensemble, meaning that only configurations with the same fixed

and

are allowed.

Because electrons are indistinguishable fermions and each single-particle state can be occupied by at most one electron (Pauli exclusion principle), the number of ways to place

electrons among the

states at energy

is

For example, if two electrons occupy three degenerate states (

), the system can be found in any of the three microstates 110, 101, or 011 at different instants in time.

Question

Is eq2 a combination?

Answer

Yes, it is. It counts the number of ways to choose occupied states out of

available single-particle states, where the electrons are indistinguishable (order does not matter) and the degenerate states are distinct because each state is defined by a unique set of quantum numbers.

It follows that the total number of microstates corresponding to a particular configuration is

Taking the natural logarithm of eq4 and substituting eq3 into it gives:

Using Stirling’s approximation. where , yields:

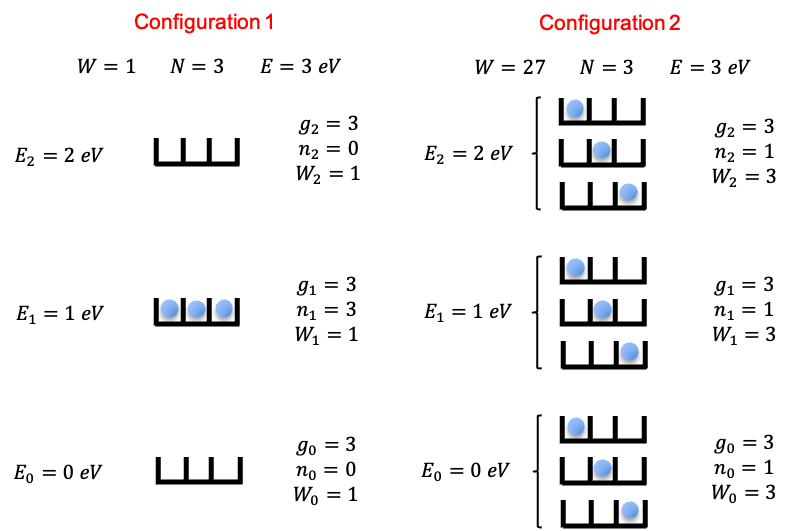

The possible configurations that define the microcanonical ensemble are restricted by eq1 and eq2. For example, the configurations and

generally have different total energies and therefore cannot both belong to the same microcanonical ensemble (see above diagram for an illustration). Within the allowed set of configurations, all corresponding microstates are equally probable. The most probable equilibrium configuration is therefore the one with the largest number of ways of achieving it, i.e. the one whose

(or

) is maximal.

The total differential of is:

Hence, we want to solve for . With reference to Step 2 of the derivation of the Boltzmann distribution using the Lagrange method of undetermined multipliers, eq6 becomes:

where we have chosen minus signs for the 2nd and 3rd terms for convenience.

Since varies independently, eq7 holds only if each coefficient is zero:

Substituting eq5 into eq8 gives:

where we have changed the summation index from to

in eq9 to discriminate the summation variable from the differentiation variable.

Since does not depend on

,

All terms in the summation of eq10 goes to zero except when . So,

Carrying out the differentiation and rearranging the result yields:

As mentioned above, is the number of electrons, which is equivalent to the number of occupied states at that level. To transform eq11 into a probability distribution, we write:

where is the probability (a fraction between 0 and 1) that a single state at energy

is occupied. Thus,

gives the expected number of electrons occupying that energy level.

Substituting eq12 into eq11 gives:

To evaluate the parameters and

, consider a system (with energy

) of the microcanonical ensemble that is partitioned by a rigid but permeable divider into two subsystems A and B, where A and B have energies

and

respectively. The total entropy

of the system is

Because the total system is also isolated, the second law of thermodynamics demands that be maximised at equilibrium. The total differential of

with respect to

is:

From , we have

. Thus, the condition for maximum entropy under energy exchange between the two subsystems at equilibrium is

Eq14 suggests that the two subsystems share a common physical property at thermal equilibrium. If we regard the electrons in each of the subsystems as a collection of non-interacting particles that move freely, much like molecules in a gas, they collectively form an electron gas. We can then use the fundamental thermodynamic equation to describe system A, where

is the chemical potential (also known as the Fermi level) of the electron gas, which has units of energy per particle instead of energy per mole. Since

and

, we have

. Similarly,

. This means that the change in entropy with respect to the change in energy is the same throughout the system:

Substituting the statistical entropy into eq15 yields:

Substituting eq8 into eq6 gives:

Substituting the derivatives of eq1 and eq2 into eq17 results in:

Substituting eq18 back into eq16 yields

Repeating the above logic, the total differential of with respect to

, where

, is:

Substituting into the above equation gives

, and using the fundamental thermodynamic equation results in:

Substituting and eq18 into eq20 yields:

Substituting eq19 and eq21 back into eq13 gives:

which is the Fermi-Dirac distribution function.

Eq22 gives the probability that an energy state is occupied by a fermion at temperature

. It plays a central role in solid-state chemistry. When the energy of the state equals the Fermi level (

), the occupancy becomes

at any

. In other words, the Fermi level

is the energy level at which the probability of finding an electron in a material is 50% at thermodynamic equilibrium for any temperature above 0 K.

The Fermi level, together with band theory, is particularly useful for understanding the electrical conductivity in metals. In semiconductors, it determines how the occupation of states in the conduction and valence bands changes with temperature and doping.

Question

What is the definition of Fermi energy?

Answer

The Fermi energy is the highest occupied single-particle state in a system of non-interacting electrons at 0 K. In metals, the Fermi level approaches the Fermi energy at absolute zero. Although the terms Fermi energy and Fermi level are often used interchangeably in chemistry and physics, especially when discussing properties at or near absolute zero, their strict theoretical definitions distinguish them.