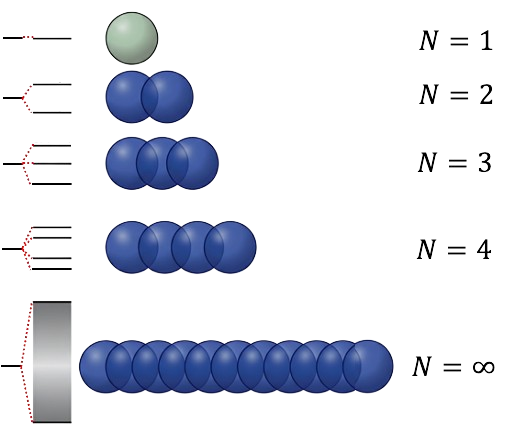

Band theory describes how atomic orbitals in a solid combine to form extended molecular orbitals, whose closely spaced energies effectively create continuous bands.

Consider a linear chain of identical atoms located at position

, with

representing the s-orbital of atom

. When two atoms overlap, molecular orbital (MO) theory states that two MOs are formed: a bonding orbital and an antibonding orbital. For three atoms, three MOs are produced — bonding, non-bonding and antibonding — while the orbital overlap of four atoms results in four MOs: two bonding and two antibonding orbitals. In general, a chain of

atoms generates

molecular orbitals. If

is large, the energy levels of these

MOs merge to form an energy band (see diagram above).

Mathematically, the energies are derived using the tight-binding model:

where ,

and

.

To show that the energies merge to form an energy band, we analyse the energy separation:

Using the trigonometric identity ,

As ,

and

in eq7.

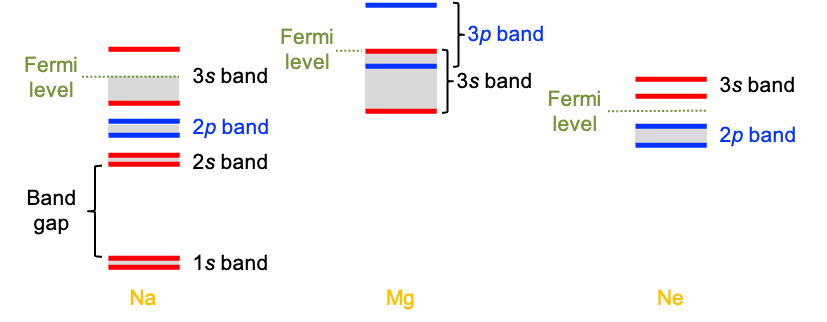

For example, the 1s-orbitals of Na, which has the electronic configuration 1s22s22p63s1, overlap to form the 1s band. Similarly, the 2s orbitals form the 2s band, and so on (see diagram above). The various Na bands do not overlap because the energy differences between different Na atomic orbitals (AOs) are much greater than the separation within each type of AO. Another characteristic of the band-MO diagram of Na is that the 3s band is only partially filled. In contrast, the 3s and 3p bands of Mg overlap to form a continuous band. Nevertheless, this merged band is still only partially filled because each 3p AO is initially unoccupied.

In metals, the Fermi energy — the energy of the highest occupied electronic state at absolute zero — lies within a partially filled band. However, it is more meaningful to associate frontier energies with the Fermi level

, defined as the energy level at which the probability of finding an electron is 50% at thermodynamic equilibrium according to the Fermi-Dirac distribution, for any temperature above 0 K.

Electronic states of metals near the Fermi energy at absolute zero arise from the overlap of many AOs and are extremely closely spaced in energy. Because the density of states varies only weakly in this region and the gaps between occupied and unoccupied states are extremely small, increasing the temperature from 0 K to room temperature excites only a tiny fraction of electrons into slightly higher-energy levels. This redistribution is so small that the energy at which the occupation probability is 50% at room temperature remains essentially the same as the Fermi energy at 0 K. Consequently, electrons can easily move into the empty states just above the Fermi level when an electric field is applied, giving metals their high electrical conductivity. This conductivity decreases at higher temperatures due to increased collisions between moving electrons and the vibrating lattice atoms (phonons), which disrupt the flow of charge.

On the other hand, solid Ne is a non-conductor. Each Ne atom has the electronic configuration 1s22s22p6, with the 2p band completely filled in the solid. The next available band (derived from 3s orbitals) lies far higher in energy, creating a large band gap. With no empty states near the top of the filled band, electrons cannot be thermally promoted into any empty states, and the material remains insulating. In such insulators, the Fermi level lies within the band gap.

![]()

The main types of semiconductors are intrinsic (undoped), p-type and n-type (see diagram above). They also possess a band gap between the valence band and the conduction band. For an intrinsic semiconductor, such as GaAs, the valence band is completely filled at absolute zero, while the conduction band is completely empty. Therefore, the Fermi level lies near the middle of the band gap. Although the gap (1.42 eV) is much larger than the thermal energy at room temperature (0.026 eV), it is still small enough that a small but statistically significant number of electrons can be thermally excited across it. Once promoted into the conduction band, these electrons can be driven by an applied electric field to produce a current. Unlike metals, the conductivity of semiconductors increases with temperature because the number of thermally generated charge carriers grow exponentially, easily outweighing the increased scattering from lattice vibrations.

When dopants are introduced into intrinsic semiconductors, they create additional electronic states within the band gap. In a p-type semiconductor, acceptor impurities introduce energy levels slightly above the valence band. At 0 K, these acceptor levels are empty, while the valence band remains fully occupied. It follows that the Fermi level lies between the valence band and the acceptor levels. Electrical conductivity arises when electrons are thermally promoted from the valence band into the acceptor levels, leaving behind mobile holes in the valence band. These holes serve as the majority carriers responsible for current flow.

n-type semiconductors contain donor levels positioned just below the conduction band. At 0 K, these donor levels are fully occupied by electrons supplied by the dopant atoms, with the Fermi level lying between the donor levels and the conduction band. When electrons are promoted from the donor levels into the conduction band, they become free to move, producing a current.

In conclusion, band theory provides a molecular-orbital perspective on how electronic structure governs conductivity across different materials and forms the foundation for devices such as transistors and solar cells.