Raman scattering is the inelastic scattering of light by molecules in which the exchanged energy reveals information about the molecules’ vibrational or rotational states.

This effect arises from the interaction between incident light and the internal energy structure of molecules, and is best understood by contrasting it with ordinary absorption. When a photon collides with a molecule and its frequency corresponds exactly to the energy difference between two stationary molecular states, the molecule can absorb the photon and undergo a real electronic, vibrational or rotational transition. In this situation, the photon’s energy matches the gap between two eigenstates of the unperturbed molecular Hamiltonian, making true absorption possible.

However, most photons do not have energies that coincide with any allowed transition. In such cases, absorption cannot occur, yet the photon may still interact with the molecule. This is the domain of Raman scattering, which is an inelastic scattering process rather than a resonant absorption phenomenon. The mechanism begins when the electric field associated with the incident photon interacts with the molecule’s charge distribution. Although the photon is detected as a particle, it propagates as an electromagnetic wave, and its oscillating electric field transiently polarises the molecule. In other words, an applied electric field can distort the molecule and induce an electric dipole moment

, with a stronger field resulting in a larger dipole moment for a given molecule:

where is the polarisability of the molecule, which is a measure of the degree to which the electrons in the molecule can be displaced relative to the nuclei.

Since and

, eq1 can also be written in matrix form as:

Here, is the

-component of

, where

denotes the direction of the applied electric field and

denotes the direction of the induced dipole moment component.

Question

Why is expressed as a rank-two tensor, known as the polarisability tensor, in eq2?

Answer

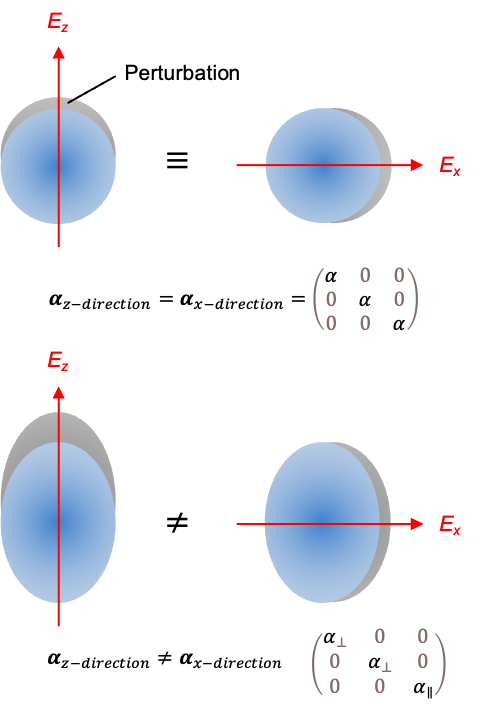

In general, the spatial distribution of electrons in a molecule is constrained by the geometry of the nuclei and the bonding orbitals. Consequently, an electric field applied in one direction can induce a redistribution of electron density in any direction permitted by those constraints, as is the case for a non-spherically symmetric molecule such as glycerol (C3H8O3). As an example, if the electric field lies along the laboratory -axis, then the distortion of the electron cloud are measured by the polarisability components

,

and

.

For spherically symmetric particles, such as an atom or a spherical rotor, the same distortion is induced regardless of the direction of the applied field, resulting in all off-diagonal elements of the tensor being zero and the diagonal elements being equal, (see above diagram). The polarisability tensor of a diatomic molecule, whether homonuclear or heteronuclear, also has zero off-diagonal elements. However,

while

, where the

-axis is chosen to be the molecular axis. Typically,

.

Furthermore, is symmetric (e.g.

) because the work done to polarise a molecule depends only on the final state of the electric field, not the path taken to reach it. If a field is applied first in the

-direction and then the

-direction, the net change in potential energy due to the molecule’s polarisability must be the same as if the fields were applied in the reverse order.

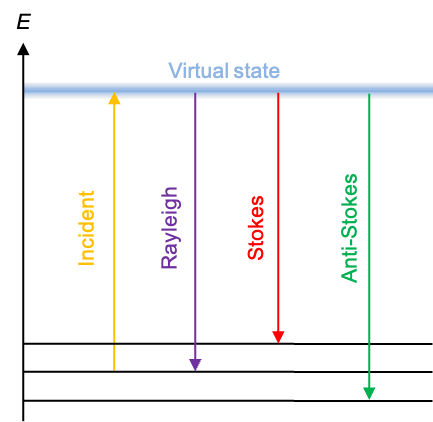

The redistributed electrons transform the molecule from its ground state into a short-lived virtual energy state. Unlike a real excited state, this state is an eigenstate of the perturbed Hamiltonian. Because it exists only during the presence of the perturbing field, the virtual state lasts on the order of femtoseconds, with its existence permitted by the time–energy uncertainty principle. Since the virtual state is not stable, the molecule quickly relaxes. If it relaxes back to the same stationary state it occupied before the interaction, the photon re-emitted has the same energy as the incident photon. This elastic process is known as Rayleigh scattering, and it accounts for the vast majority of scattered photons (see diagram below).

But if the molecule relaxes to a different stationary vibrational or rotational state than the one it started in, energy must be conserved by adjusting the energy of the scattered photon accordingly. If the molecule ends up in a state of higher internal energy, the scattered photon necessarily loses that amount of energy and emerges with a lower frequency (Stokes scattering). Conversely, if the molecule relaxes to a lower one, the scattered photon gains the excess internal energy and is emitted with a higher frequency (anti-Stokes scattering). These two types of scattering are collectively known as the Raman effect or Raman scattering.

Thus, Raman scattering provides a window into the vibrational and rotational structure of molecules: the energy shifts — Stokes and anti-Stokes — encode the quantised energy differences between molecular states. By measuring these shifts, Raman spectroscopy reveals the “fingerprint” of molecular vibrations, enabling powerful chemical identification and structural analysis without requiring the incident light to resonate with any real molecular transition.

However, due to the instantaneous orientation of the molecule, different photons colliding with it may lead to different extents of polarisation according to the polarisation tensor. The transition probability for Raman scattering is even lower, at about one in ten million. Therefore, Raman spectroscopy requires a high-power laser source, with the complete instrumentation described in the next article.