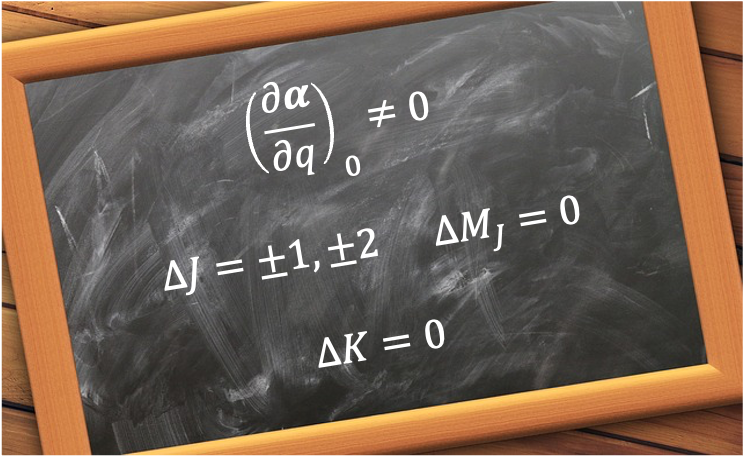

Rotational Raman selection rules for symmetric rotors describe the allowed changes in a symmetric top’s rotational angular momentum states during inelastic light scattering.

A symmetry rotor, such as CH3Cl, has a permanent electric dipole moment along its symmetry axis. At finite temperatures, the total angular momentum of the rotating molecule is generally not parallel to the symmetry axis and given by:

where is the unit vector along the symmetry axis.

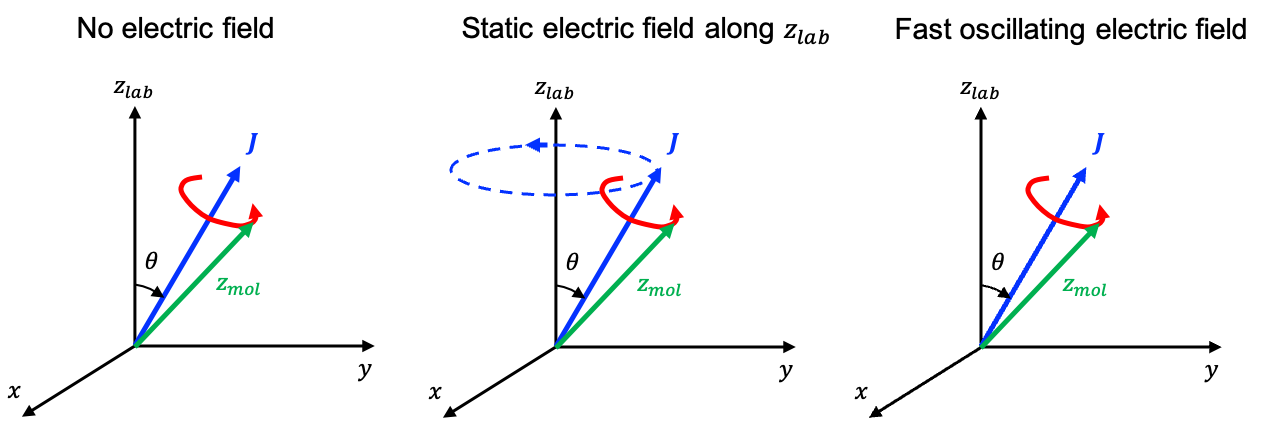

In the absence of external interactions (e.g. an electric field), the vector is conserved. This is because space is isotropic and the physics is unchanged regardless of the orientation of the molecule. It follows that the symmetry axis of the molecule must precess around

so that its projection onto

stays constant as the molecule rotates (see diagram below).

Question

Why must the projection of the symmetry axis of the molecule onto remain constant as the molecule rotates?

Answer

The rotational energy of the molecule is given by:

where is the projection of

onto the symmetry axis.

Substituting into

gives:

For a given ,

is conserved, and the two moments of inertia are also constant. Therefore,

must be a constant. Since, the projection of

onto the symmetry axis and the projection of the symmetry axis onto

are related by the same constant angle, the projection of the symmetry axis of the molecule onto

remains constant as the molecule rotates.

In the presence of a static electric field, the interaction of the field with the molecule’s electric dipole moment generates a torque on the molecule given by

where is the angle between

and

.

This torque changes the molecule’s angular momentum vector according to

Because the torque is perpendicular to the electric field direction (taken as the lab -axis), its component along the field axis is zero. Consequently, the projection

of

onto that axis cannot change. The only way for

to change over time, while keeping a constant projection onto the lab

-axis is for it to precess around the direction of the electric field.

As a result, the molecular axis undergoes a compound motion with a fast precession around and a slower precession of

around the static electric field line (see above diagram). However, in Raman spectroscopy, the laser produces an electric field that oscillates at about 1014 to 1015 Hz, which is much faster than the molecule can physically rotate or precess. The interaction between the field and the molecule’s permanent dipole averages to zero, resulting in no net torque on the permanent dipole and hence no precession of

around the electric field line.

While the permanent dipole interaction averages to zero, the induced dipole interaction does not, because it is not confined to the molecular axis. Nevertheless, the interaction between the induced dipole and the electric field is typically very weak, leaving the precession of the molecular axis around as the dominant motion.

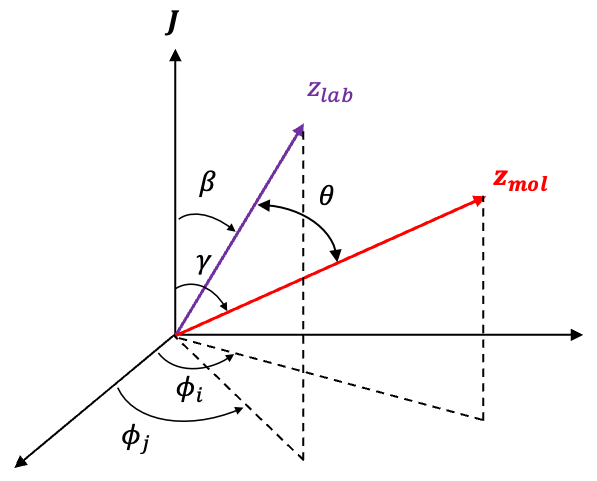

In the molecular frame, the polarisability tensor of a symmetric rotor is mathematically identical to that of a linear molecule. This because both linear rotors and symmetric rotors possess cylindrical symmetry (or higher) about their principal axis. It follows that the projection of the molecular induced dipole moment onto the direction of the electric field (laboratory -axis) is given by eq7a, or equivalently,

where .

Substituting the spherical law of cosines (see diagram above), where into eq20 gives:

Expanding the equation and using the identity yields:

where

The selection rules involving the quantum number can be explained semiclassically, with the induced dipole moment given by:

where is the angular frequency of the incident radiation.

Substituting eq21 into eq22 results in:

Using the identity gives:

This equation shows that the induced dipole moment consists of five components: one oscillating at the incident frequency, two at , and two at

. Each time-dependent component of the induced dipole moment corresponds to an oscillating dipole, which radiates electromagnetic energy at the frequency at which it oscillates. It follows that the component oscillating at

gives rise to Rayleigh-scattered radiation, while those at

and

produce Raman-scattered radiation.

Question

Why does each component on the RHS of eq23 correspond to an oscillating, rather than the entire sum corresponding to a single oscillating dipole?

Answer

An oscillating electric dipole is defined by a dipole moment that varies sinusoidally in time at a single frequency, for example . Therefore, eq23 represents a superposition of five independent sinusoidal components, which can be viewed as a Fourier decomposition of the induced dipole moment. Each term oscillates at a distinct frequency and therefore corresponds to an independent oscillating dipole that radiates at that frequency.

Raman selection rules are often discussed for thermally populated rotational levels, where is typically large (the classical limit). For large

, the magnitude of the quantum angular momentum of the molecule is

. Substituting this approximation into

gives:

is the angular frequency of a Stokes-scattered photon, which is associated with the resultant quantum rotational transitional frequency of

. This corresponds to the selection rule

, because at large

,

Similarly, the angular frequency (anti-Stokes scattering) leads to the selection rule

, while

corresponds to

. For the selection rules involving the remaining quantum numbers

and

, we refer to the time-dependent perturbation theory, which states that the transition probability

can be found by evaluating:

where and

are the Wigner D-functions.

The integrals and

are non-zero only if

and

. This confirms that we require

and

for a probable transition to occur (

).

Therefore, the combined selection rules for rotational Raman transition of a symmetric rotor are: