A superconductor is a material that, below a certain critical temperature, conducts electricity with zero electrical resistance and expels magnetic fields.

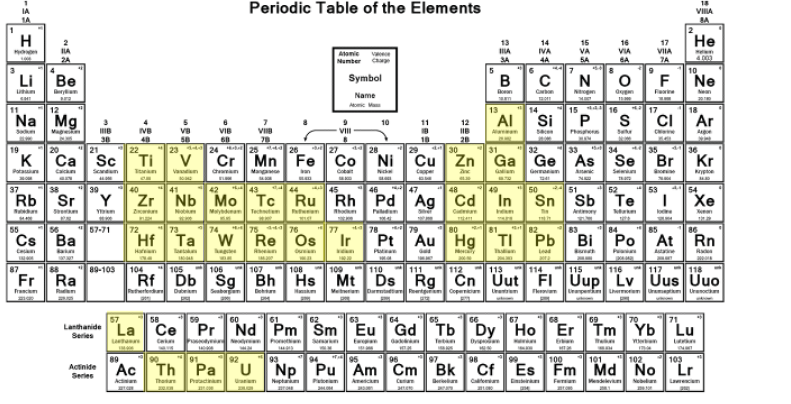

The first superconductor was discovered in 1911, when Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes observed that mercury’s electrical resistance suddenly vanished at about 4.2 K. In the years that followed, additional elements were identified as superconductors, with critical temperatures below 23 K. These superconducting elements are mostly transition metals that are bunched into certain parts of the periodic table (elements highlighted in yellow in the above diagram). In contrast, the noble metals (such as copper, silver and gold) and the alkali metals generally do not become superconducting at ambient pressure.

Metals normally resist the flow of electricity. Electrons, the carriers of current, constantly scatter off vibrating atoms (phonons), impurities and even each other. Yet, below a certain temperature, some metals suddenly lose all electrical resistance.

How can electrons stop scattering entirely? The answer lies in a profound insight developed by John Bardeen, Leon Cooper and Robert Schrieffer, known as the BCS theory.

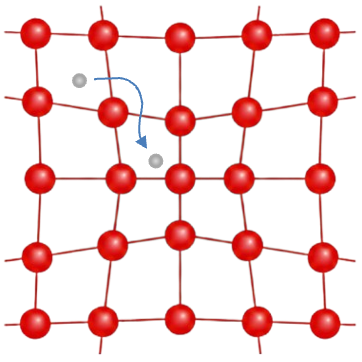

According to this theory, electrons stop acting like isolated particles. Instead, they form highly coordinated pairs that move in perfect harmony, allowing current to flow without energy loss. At first glance, the idea that electrons can pair seems impossible. After all, they repel each other electrically. But the key insight is that electrons can interact indirectly through the crystal lattice. When an electron moves through a lattice, it slightly attracts the positively charged ions nearby, creating a tiny distortion. This distortion, in turn, can attract a second electron (see diagram below). This effective attraction is extremely weak, only acts for electrons near the Fermi surface, and operates within a narrow energy range. Such a phonon-mediated interaction is generally isotropic (the same in all directions) in momentum space, or at least does not have a strong directional dependence.

In 1956, Leon Cooper showed that if even the tiniest attraction exists between two electrons just above the Fermi level, they will inevitably form a bound pair — a Cooper pair. Essentially, the enormous density of available electronic states near the Fermi surface acts like a magnifying glass for even the tiniest attractions. Because so many states are packed closely together, two electrons with a weak attractive interaction have an overwhelming number of ways to pair up. This abundance of possibilities amplifies the effect of the weak attraction, making it sufficient to bind electrons into a Cooper pair. Even interactions that would be negligible elsewhere in the energy spectrum become decisive near the Fermi surface, ensuring that pairing always occurs when conditions are right.

A Cooper pair isn’t two electrons clinging together like magnets. It is a quantum superposition extending over thousands of lattice spacings, characterised by:

-

- A total spin of 0 (singlet)

- A total momentum of 0 (electrons at

and

)

- A highly delocalised wavefunction that strongly overlaps with others

The wavefunction of the Cooper pair is given by:

where

is a function describing the amplitude

is an operator that creates an electron with momentum

and spin

is an operator that creates an electron with momentum

and spin

is the vacuum state where the system has zero particles

Question

Why does the Cooper pair have zero momentum?

Answer

In conventional superconductors, a Cooper pair with a total linear momentum of zero minimises kinetic energy, making this configuration energetically favourable. As the phonon-mediated interaction is approximately isotropic in momentum space, the Cooper pair’s spatial wavefunction is spherical with zero angular momentum .

Electrons are fermions and the total wavefunction must be antisymmetric under exchange of the two electrons. The total wavefunction of the pair is the product of a spatial part, which is symmetric (), and a spin part, which must then be antisymmetric, forming a singlet.

Because the wavefunctions overlap so extensively, all Cooper pairs in the metal lock into a single quantum state. This creates a kind of “quantum super-traffic-jam,” where every pair is aware of every other pair through a shared phase. When billions of Cooper pairs occupy the same quantum state, they form a macroscopic quantum condensate, a unified wavefunction stretching across the entire metal. This condensate is rigid and tiny disturbances cannot knock individual pairs out of step.

How then is the material able to conduct electricity without resistance? Resistance arises when electrons scatter off imperfections or vibrations. Cooper pairs, however:

-

- Are spread out over huge distances

- Share a common quantum phase

- Cannot scatter individually

For a Cooper pair to scatter, all pairs must do so simultaneously, which requires a prohibitive amount of energy. Small impurities or low-energy phonons simply cannot disrupt this concerted motion. Once the condensate begins moving, it keeps moving forever unless something strong enough breaks the pairs. Furthermore, breaking a Cooper pair costs energy, creating the superconducting energy gap. This gap shields the condensate from thermal fluctuations, explaining why superconductors exhibit zero electrical resistance and persistent currents at low temperatures where phonon-mediated interactions are not disrupted by thermal motion of lattice ions. In other words, electrons in a superconductor below its critical temperature move together forever, without resistance.

This remarkable ability to carry persistent currents without energy loss is directly exploited in technologies that require stable, intense magnetic fields. For example, in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines, niobium-titanium coils are cooled below their critical temperature (10 K) with liquid helium to form persistent currents. These currents generate strong and extremely stable magnetic fields, which are essential for producing high-resolution images of internal tissues. Because the currents circulate indefinitely without decay, MRI magnets do not require continuous power input to maintain their fields, making them highly efficient and reliable. Beyond medical imaging, the same principle is exploited in quantum computing, where persistent, lossless currents are critical.

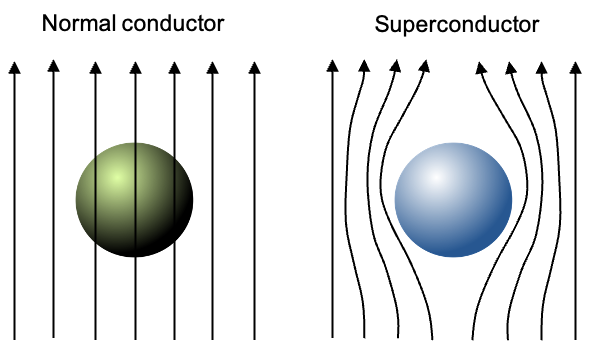

The second defining property of a superconductor is its ability to expel magnetic fields from its interior, such that . This phenomenon is called the Meissner effect, and it occurs even if an external magnetic field was already present before the material was cooled.

In a normal conductor, magnetic fields penetrate the material almost uniformly (see diagram above), limited only by weak and short-lived effects such as induced eddy currents. If the external magnetic field changes with time, Faraday’s law generates eddy currents in the conductor, but these currents quickly decay because the material has finite electrical resistance. As they die out, they no longer oppose the applied field, allowing the magnetic field to fully penetrate the bulk.

In contrast, when a superconductor cools below , Cooper pairs form and create a coherent superconducting condensate. In the presence of an external magnetic field, the condensate develops spatial variations that raise its kinetic energy, which in turn induces circulating screening currents along the surface. These currents generate magnetic fields that exactly oppose the applied field inside the material. Because the resistance is zero, the screening currents persist indefinitely without any power source, maintaining complete magnetic field expulsion.

Consequently, when a magnet is brought near a superconducting material, the induced screening currents produce a magnetic field that repels the magnet. This repulsive force can counteract gravity, allowing the magnet to float or levitate above the superconductor. Conversely, if the superconductor is placed above a magnet, it can also hover, held in place by the interaction between its induced currents and the magnetic field.

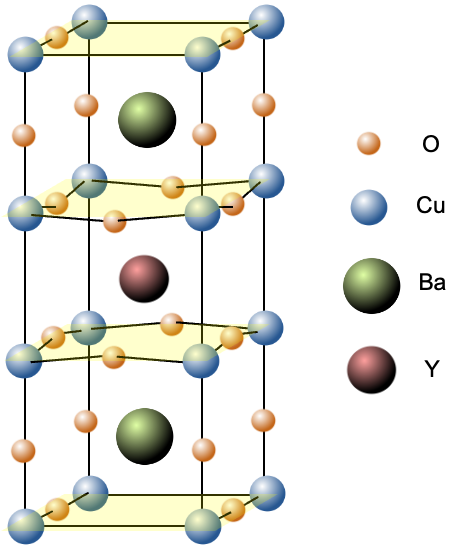

This principle of magnetic levitation can be harnessed to create frictionless transportation. In 1986, high-temperature superconductors ( of up to 138 K) were discovered. These materials, typically containing copper oxide and other metals such as barium and yttrium, are exemplified by YBa2Cu3Ox (

), where

.

In maglev trains, YBa2Cu3Ox magnets are mounted on the train and cooled inside well-insulated chambers using liquid nitrogen. These magnets interact with permanent magnets or electromagnets embedded in the track, causing the train to levitate and eliminating friction with the track. By carefully controlling the magnetic fields along the track, the train can also be propelled forward. Changing the position or intensity of the track’s magnetic fields induces forces on the superconducting magnets via electromagnetic induction, pushing or pulling the train along its path. The combination of frictionless levitation and contactless propulsion allows maglev trains to achieve very high speeds with minimal energy loss, making them a highly efficient transportation technology.

Question

Why is Yba2Cu3Ox a superconductor when the individual elements are not superconducting?

Answer

YBa2Cu3Ox has a layered, perovskite-like crystal structure, with alternating layers of CuO₂ planes and other layers containing yttrium and barium (see above diagram for the unit cell of YBa2Cu3O7). The CuO₂ planes are where superconductivity primarily occurs, while the other layers act as charge reservoirs and provide structural support for the lattice. This arrangement creates an energetically favourable environment in which the electronic properties necessary for superconductivity can emerge.

Within the CuO₂ planes, strong hybridisation between copper orbitals and oxygen

orbitals creates an extensive two-dimensional network of electronic states. The superconductivity itself is enabled by controlling the oxygen content through a process known as doping, which introduces holes (positively charged carriers) into the planes. These holes are the microscopic charge carriers that pair up to form Cooper pairs.

Furthermore, the two charge carriers that form a Cooper pairs in the CuO₂ planes are much more tightly bound than in conventional superconductors. This results in a very short coherence length (the characteristic size of a Cooper pair) of only a few nanometres, compared with the tens to hundreds of nanometres typical in phonon-mediated superconductors such as NbTi. The short coherence length reflects a much stronger effective attractive interaction, likely arising from magnetic (spin-fluctuation) mechanisms rather than phonons. This stronger pairing interaction is one of the key reasons YBa₂Cu₃Oₓ can sustain superconductivity at temperatures far higher than those of conventional superconductors.

In essence, superconductivity in YBa2Cu3Ox is not due to the individual elements, but emerges from the specific arrangement of copper and oxygen atoms in the planes, combined with proper doping and crystal structure.