Selection rules for scattered radiation describe the allowed changes in a molecule’s state during light scattering.

According to the time-dependent perturbation theory, the transition probability between the orthogonal states

and

is proportional to the square of the corresponding transition matrix element

. For example, in conventional rotational spectroscopy, this involves the electric dipole moment operator

, and transitions occur only for molecules with a permanent dipole moment.

Transitions associated with scattering radiation, however, arise from an induced dipole moment rather than a permanent one. It follows, with reference to eq1, that the transition probability is given by:

Thus, a necessary condition for scattered-radiation transitions is that the matrix element be non-zero. To examine this condition further, we consider how the molecular polarisability

depends on the molecular coordinate

, which may represent a rotational angle or a vibrational displacement. This dependence can be expressed through a Taylor series about the equilibrium configuration:

Substituting this series (and neglecting higher-order terms) into gives:

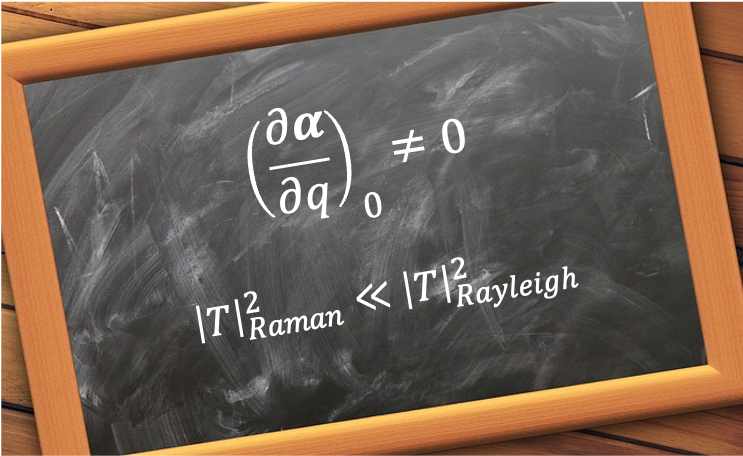

Because the wavefunctions are orthogonal, the first term vanishes unless , which corresponds to Rayleigh scattering. Consequently, a Raman transition can occur only if

, i.e. the polarisability of the molecule must change as it undergoes rotational or vibrational motion.

When , we have

, which is the transition probability for Rayleigh scattering. When

, we have the transition probability for Raman scattering:

Since represents a small perturbation of the electron cloud of the molecule,

. Furthermore, the magnitude of the transition matrix element

is never large: for vibrational Raman scattering it is proportional to the small zero-point vibrational amplitude, while for rotational Raman scattering it is a dimensionless angular matrix element bounded by unity. Consequently,