A good quantum state is an eigenstate of the system Hamiltonian whose associated quantum numbers are conserved and uniquely label the state.

Such states arise from the symmetries of the Hamiltonian. As eigenstates of the Hamiltonian, they are unchanged under time evolution apart from an overall phase and provide a stable basis for describing physical observables and selection rules by enabling the diagonalisation of the Hamiltonian.

For example, a hydrogen atom is described by the good quantum state if spin-orbit coupling is ignored. The principal quantum number

counts the number of radial nodes in the electron wavefunction, which is fixed for a given energy level. Therefore,

remains conserved, and energy shells labeled by

are always well-defined, making it a good quantum number. The remaining quantum numbers are also good quantum numbers because their corresponding operators commute with the Hamiltonian

. We refer to

as an uncoupled basis state.

Question

Show that ,

and

commute with the non-relativistic Hamiltonian for a one-electron system.

Answer

For and

, see the Q&A in this article by replacing

and

with

and

.

The non-relativistic Hamiltonian involves only spatial coordinates. Since

acts on a different Hilbert space (spin coordinate

), it always commutes with

:

However, when spin-orbit coupling is included, the Hamiltonian for the hydrogen atom is given by , where

is the non-relativistic Hamiltonian and

is the perturbation due to spin-orbit coupling. In this case,

and

are no longer good quantum numbers, and the system is described by the good quantum state

, known as the coupled basis state.

remains good because

is a weak perturbation that does not significantly mix energy states labelled by it.

also remains a good quantum number because

(see 2nd Q&A below for details).

Question

What is a mixing of energy states?

Answer

“Mixing” means that energy states are perturbed. These new energy levels can no longer be described by a stationary-state like , but instead by a linear combination, e.g.:

This new state does not have a single value for or

, making them “bad” quantum numbers.

As mentioned eariler, commutes with

. It also commutes with

because

So, and

is proportional to

Question

Why is ?

Answer

Since any operator commutes with itself, . For the 2nd term,

and

commute because they act on different Hilbert spaces (space vs spin). Expanding

gives:

Using the identity , we find that

. Substituting

into the 3rd term and applying the same logic yields

.

Since commutes with both

and

, we have

, with

being a good quantum number. It follows that

is a good quantum number because

.

In the presence of an external magnetic field, the classification of a quantum number as “good” or “bad” depends on which interaction dominates the physical behaviour of the system. The Hamiltonian for the hydrogen atom becomes:

where is the perturbation due to the Zeeman effect.

In a weak magnetic field, where , the spin-orbit interaction is the dominant perturbation and

remains a good quantum state. The weak Zeeman field slightly shifts these states but is too weak to significantly mix states of different

. In this sense,

may be regarded as a “mostly good” quantum number, allowing the energies to be calculated accurately using perturbation theory.

In a strong external magnetic field , torques are generated separately on the orbital and spin magnetic moments,

and

, with the vectors

and

antiparallel to

and

respectively. Each torque,

or

, is perpendicular to the external magnetic field direction (taken as the lab

-axis), so its component along the field axis is zero. Consequently, the projections

and

cannot change. The only way for

and

to evolve in time while maintaining constant projections onto the

-axis is for them to precess independently about the direction of the magnetic field. Hence,

and

become good quantum numbers again, and the state returns to the uncoupled form

.

Question

Does any precession occur in the hydrogen atom in the absence of an external magnetic field?

Answer

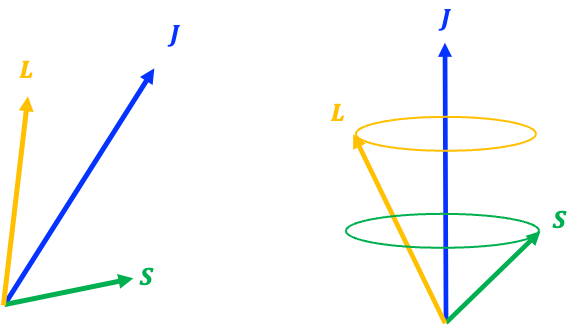

Yes, it does. In the rest frame of the electron, the positively charged nucleus orbits the electron. Since a moving charge creates a magnetic field, an internal magnetic field parallel to

is produced from the electron’s perspective by its own orbital motion.

interacts with the electron’s spin magnetic moment

, generating a torque:

Mathematically, this requires to precess about

. However, if

were constant while

precessed around it, the total angular momentum

would change. However, in an isolated atom,

must be conserved. To ensure this, an equal and opposite torque acts on

as the internal interaction pulls on

, causing both

and

to evolve in time. The only way for both

and

to change while keeping

constant is for them to precess about their vector sum

(see diagram below).

In the presence of a strong external magnetic field , the precessional motion due to the interaction of

with

becomes dominant, overwhelming the mutual precession of

and

around

. This leads to the decoupling of

and

.

Next article: Zeeman effect

Previous article: Good quantum number

Content page of quantum mechanics

Content page of advanced chemistry

Main content page