The Laue equations are formulated in 1914 by Max Theodor Felix Laue, a German physicist. Like the Bragg equation, they serve to explain X-ray diffraction patterns.

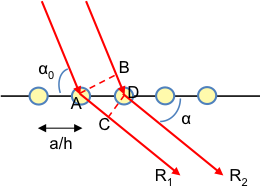

Consider a one-dimensional row of equally spaced lattice points of a crystal in the diagram above. If , the path difference δ between R1 and R2 is given by

Since and

,

For constructive interference to occur, the path difference must be an integral multiple of the wavelength of the X-ray radiation. So,

Similarly, for the other two axes of the crystal, we have:

Eq15, eq16 and eq17 are collectively known as the Laue equations. For constructive interference to occur in three dimensions, the three equations must be simultaneously satisfied.

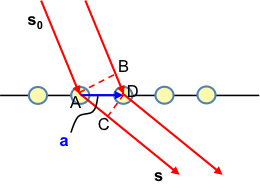

The Laue equations can also be expressed in vector form (see above diagram), where s and s0 are wave vectors of the scattered and incident X-rays respectively; a is the lattice vector along the a-axis. Again,

Since and

,

. Similarly,

. So,

Substituting (see below for explanation) in eq18,

For constructive interference to occur,

Similarly, for the other two axes, we have,

Eq20, eq21 and eq22 are the Laue equations in vector form.

Question

Why is ?

Answer

A wave vector k, like any vector, has a direction and magnitude. Its direction is perpendicular to the wavefront, while its magnitude is defined as the number of waves per unit distance, which is 1/λ. Therefore, .

Wave vectors and have origins in the de Broglie relation, which is p = h/λ = hk where k = 1/λ. Since p is a vector, k must also be a vector, as h is a constant, i.e. p = hk. This implies that k is also a momentum vector with magnitude of 1/λ.