A symmetry-adapted linear combination (SALC) is a function that consists of a sum of basis functions that are related by symmetry transformations. SALC wave functions of a molecule are building blocks of a molecular orbital (MO) of the molecule. Such SALCs of a certain symmetry combine with other atomic orbitals of the same symmetry to form MO wave functions, which can be used as trial functions in the Hartree-Fock-Roothaan procedure to calculate energy states of a molecule. These energy states are eventually presented in an MO diagram.

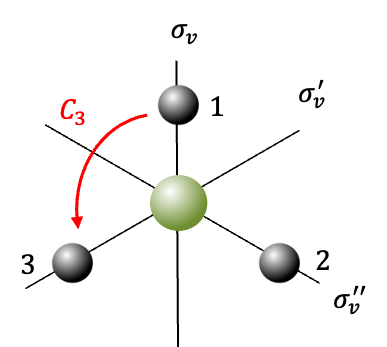

Consider the molecule . The first step is to choose a basis set to generate a representation of the

point group, which the molecule belongs to. The choice of a basis set is related to the way bonds are formed in

. The elements of the set may be vectors representing the bonds or wave functions of atoms forming the bonds. For this example, we shall use the basis set of valence

-orbitals

of the four atoms.

Question

How do we know if the basis set that we have chosen transform according to a representation of the point group?

Answer

Since a symmetry operation transforms into an indistinguishable copy of itself, each of the element of the basis set transforms into another element of the set. We can therefore express the transformation as eq55, which implies that the set generates a representation of the

point group.

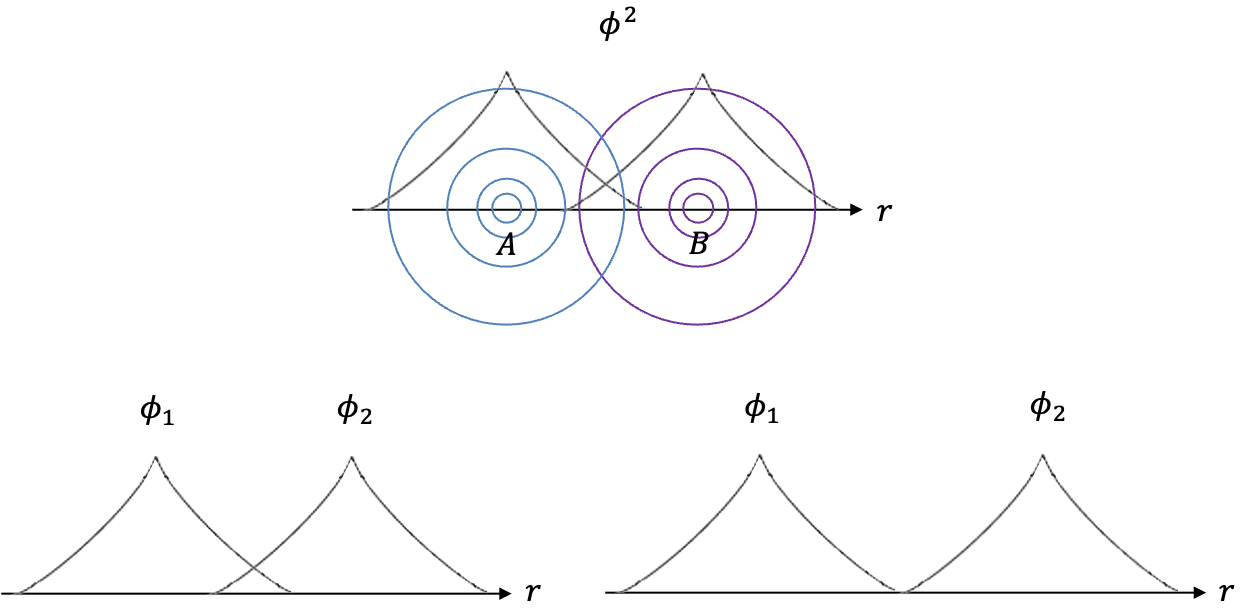

The diagram above shows the four orbitals, with the principal axis of rotation perpendicular to the plane of the screen. Symmetry operations acting on the basis set produce the following results:

The corresponding matrix transformation equations are:

The transformation matrices form a reducible representation of the

point group:

Question

-

- How do we verify that the matrices form a representation of the

point group?

- Why is

a reducible representation?

- How do we verify that the matrices form a representation of the

Answer

-

- Check that they satisfy the closure property of the group.

- The original

character table before the addition of

has no 4-dimensional irreducible representation. Therefore,

must be reducible.

Using eq27a, we have

which implies that the decomposition of the reducible representation is .

Applying the projection operator on for

,

This means that , which is an SALC that normalises to

, is a basis for

. Similarly, the projections of

and

for

result in

, while the projection of

for

returns

.

Question

How do we normalise ?

Answer

Since , we have

.

Applying the projection operator on ,

,

and

for

, we have

Since the number of orthogonal basis functions of a representation corresponds to the dimension of the representation (see this article for explanation), there are four orthogonal basis functions for . If the first two are

and

, the remaining two must transform according to

(see Q&A below for explanation).

Question

Explain the last sentence in the above paragraph.

Answer

A symmetry operation sends each orthogonal basis into another linear combination, whose coefficients form a column of the matrix representation

under that symmetry operation (see this article for explanation).

is related to

by a similarity transformation. This implies that they are equivalent and have the same trace.

can also undergo a similarity transformation to block-diagonal form

because it is a reducible representation. The blocks correspond to the direct sum of

. Therefore, we can select a set of four orthogonal basis functions that transform according to

, with the coefficients of each basis function forming a column entry for

. Since the first two basis functions generate two columns corresponding to

and

, the last two basis functions must produce the columns corresponding to

.

However, the normalised functions ,

,

and

are not orthogonal to each other. To find the two remaining orthogonal basis functions for

, we arbitrarily select

as one the two functions. As any linear combination of a set of functions that transforms according to

is a basis of

that is equivalent to

(see this article for explanation), the other basis SALC function is determined by taking a linear combination of

,

and

, e.g.

, which normalises to

.

Question

Show that is orthogonal to

but not orthogonal to

.

Answer

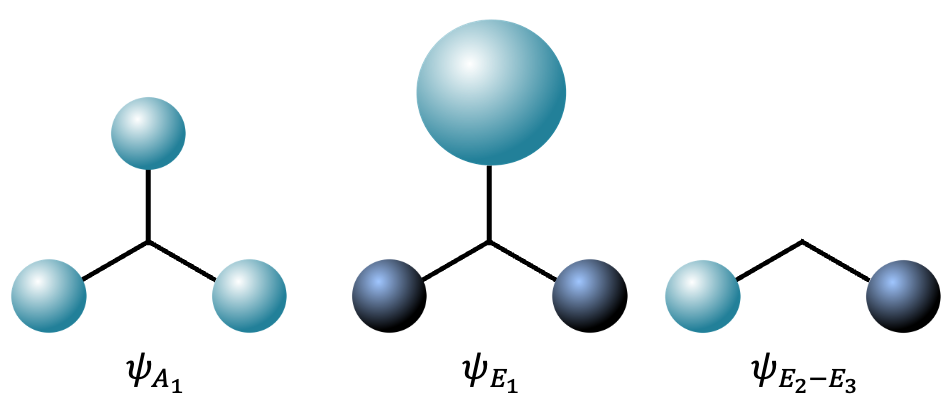

Therefore, the three orthogonal SALC functions describing the orbitals of the three hydrogen atoms (see above diagram) are

,

and

. They combine with the atomic orbitals of the central nitrogen atom to form MO wave functions, which will be further elaborated in the next article.