A Spontaneous process is an irreversible process that occurs naturally under certain conditions in one direction, but requires continual external input in the reverse direction. An example is the flow of heat from a hot body to a cold body.

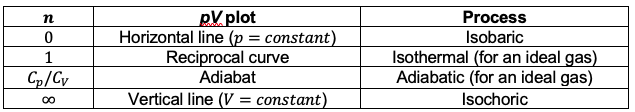

Consider a closed system with 1 mole of a monoatomic gas at that is brought into contact with another compartment, which contains the same amount of the same gas at

(see diagram above). The green boundary is thermally insulating, while the blue divider is thermally conducting. If

, heat will flow from the system to the compartment on the right. Such a process is an irreversible process because the thermodynamic properties of the initial and final states of the system, but not the intermediate states, are well-defined. For example, the temperature of the system near the divider will be different from the temperature of the system further away from the divider when the system is first brought into contact with the right compartment. When both compartments attain thermal equilibrium, the system can only be reversed to its initial state via a heat pump (continual external input).

Question

Why does heat always flow from a high temperature body to a low temperature body?

Answer

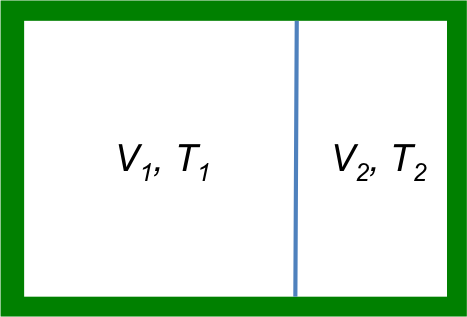

The heat content of a substance is the total energy of motion of particles making up that substance, while the temperature of a substance is a measure of the average energy of particle motion in that substance. An easy way to understand the flow of heat is to study the motion of a monoatomic perfect gas, which consists entirely of kinetic energy. Consider two compartments that are separated by a thermally insulating valve (see diagram above). The left compartment contains 1 mole of a monoatomic gas at , while the right compartment houses the same amount of the same gas at

, with

i.e.

. If the separator is removed, atoms move randomly in an enlarged volume, with those on the left moving to the right faster than those on the right moving to the left. Over time, an even distribution of atoms is achieved in the container, where the average kinetic energies per unit volume sampled from different parts of the container (

) are the same. Since

, heat must have flowed from the left to the right.

If we consider energy transfer during collisions, i.e. we no longer have a perfect gas, we end up with the same conclusion. In the case of elastic collisions, the conservation of momentum and kinetic energy lead to:

Combining the two equations and letting , we have

and

. This means that any two colliding gas atoms exchange their initial velocities, resulting in an equal distribution of atomic velocities and the same average velocity in any sampled volume.

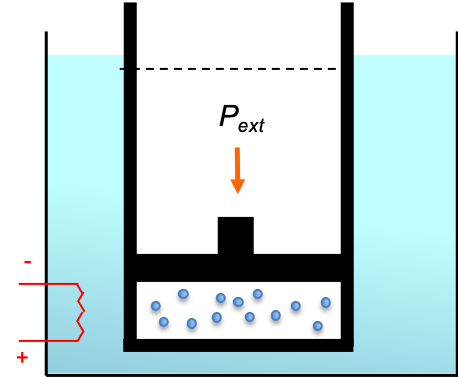

Another example of a spontaneous process is the irreversible expansion of a system consisting of a gas in an isolated vertical cylinder (see diagram below).

If the force exerted by the gas on the bottom surface of the frictionless piston is greater than the weight of the piston, the gas expands and pushes the piston up when the catches are removed. The piston moves over a distance until the force exerted by the expanded gas on the bottom surface of the piston equals to the weight of the piston. This process is an irreversible one since there is only sufficient time for the gas to equilibrate at the start and at the end of the process. To return the system to its initial state, we need to push the piston down over the same distance (continual external input).