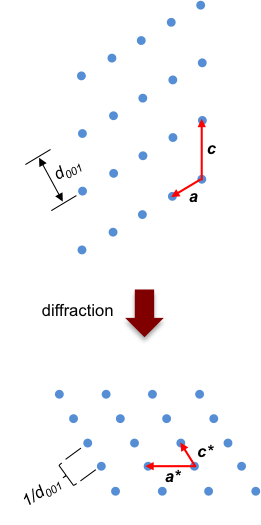

A reciprocal lattice is the diffraction image of a real crystal lattice. It is formed by linear combinations of basis vectors of the reciprocal space.

In an earlier article, we mentioned that the three Laue equations must be simultaneously satisfied for constructive interference to occur in three dimensions. In other words, the solution to the Laue equations is a mathematical description of the diffraction pattern of an X-ray diffraction experiment.

Let h = (s – s0) and we can rewrite eq20, eq21 and eq22 as:

A general solution to the simultaneous equations of eq24a, eq24b and eq24c is:

where ,

and

. V is the volume of the unit cell formed by the basis vectors a, b and c.

Question

Show that eq24d is a general solution to the Laue equations.

Answer

Substitute eq24d in eq24a

Since (c × a) is a vector that is perpendicular to the plane formed by c and a, a · (c × a) = IaI Ic × aI cos90º = 0. By the same logic, a · (a × b) = 0. Therefore,

Since a · (b × c) = V (see below for proof), LHS = RHS. We can substitute eq24d in eq24a and eq24b with similar results.

The vector h in eq24d is also a lattice vector but with basis vectors of a*, b* and c* instead of a, b and c. The dimension of a* is length-1 because , where n is a unit vector in the direction of a* (the unit vector n is necessary because a* is a vector but

is a scalar). Similarly, b* and c* have dimensions of the reciprocal of length. Hence, h is known as a reciprocal lattice vector.

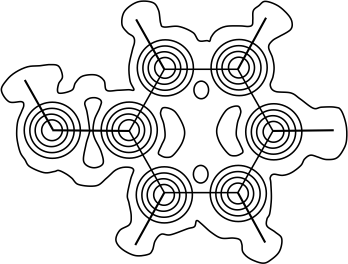

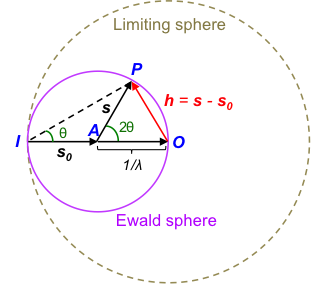

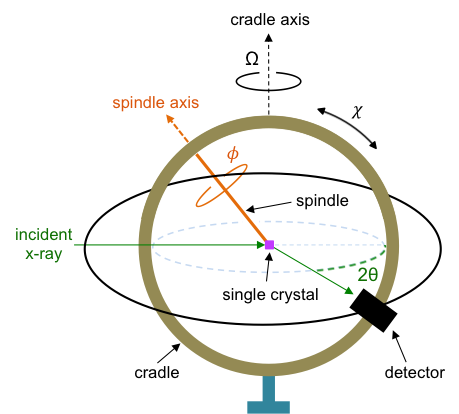

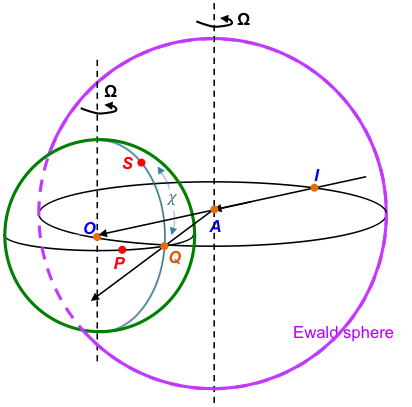

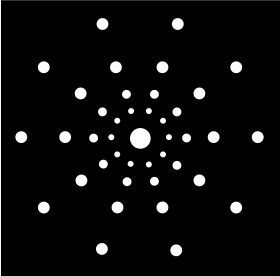

Just as a lattice vector describes the positions of lattice points in a space lattice, the reciprocal lattice vector mathematically defines the positions of lattice points in a reciprocal space lattice, which means that the diffraction pattern is constructed in a reciprocal space (see diagram below).

Even though the reciprocal lattice and the Ewald sphere allow crystallographers to visualise diffraction patterns in relation to various X-ray diffraction techniques, Bragg’s law is most often used to explain X-ray diffraction concepts. This is because Bragg’s law is easier to apply than the Laue equations, and in some cases involves the knowledge of just an angle θ to deduce the unit cell types and unit cell dimensions of a sample.

Question

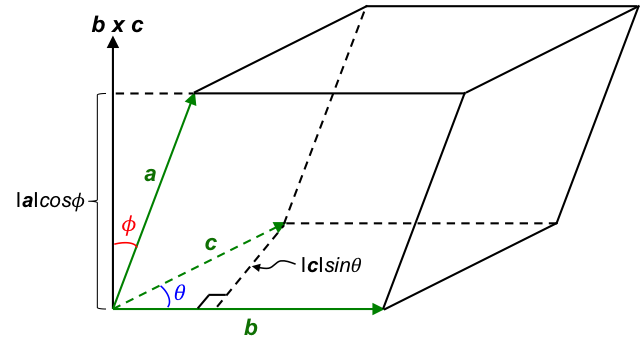

Show that a · (b × c) = V.

Answer

With reference to the above diagram, a, b, c are the basis vectors of the unit cell. The area of the base of the unit cell, which is a parallelogram, is:

The volume of the unit cell, V, is:

a · (b × c) is known as the scalar triple product.