A reaction mechanism is a stepwise molecular depiction of the way reactants interact to formed products in a chemical reaction. It is represented by one or more balanced chemical equations depending on whether the type of reaction it is describing is an elementary reaction or a complex reaction, respectively.

An elementary reaction is a chemical reaction where one or more species react in a single step to form products via a transition state. An example is the thermal decomposition of phosphorous (V) chloride:

Elementary reactions are classified according to their molecularity, which is the number of molecules reacting to form products in an elementary reaction.

| Molecularity | Mechanism | Rate law | Order | Example |

| Unimolecular | 1st | |||

| Bimolecular | 2nd | |||

| Trimolecular or Termolecular | 3rd | |||

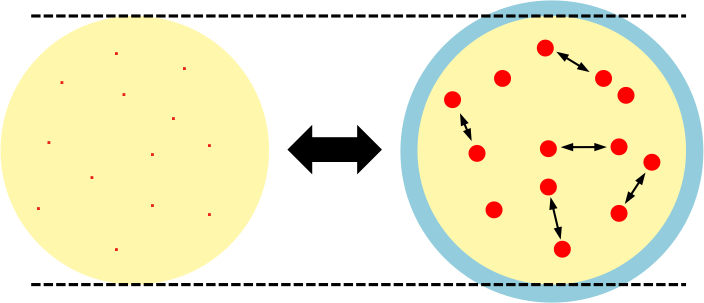

A unimolecular reaction involves a species rearranging its bonds or dissociating to form products. Bimolecular and termolecular reactions occur when two and three molecules respectively collide to form products. The probability of elementary reactions involving the simultaneous collision of more than three molecules is very low.

From the table above, the rate law and hence the order of an elementary reaction can be predicted from the molecularity of the reaction, where unimolecular, bimolecular and termolecular reactions are, overall, first, second and third order reactions respectively.

As mentioned above, one or more species in an elementary reaction react via a transition state to form the products. The transition state is a point of highest potential energy on the potential energy profile curve of a reaction. It is where an unstable, transient and non-isolable chemical structure called an activated complex is formed (see diagram below).

For example, the bimolecular reaction between bromomethane and hydroxide ion to give methanol proceeds through the activated complex (denoted by ), where the C-Br bond weakens and the C-OH bond starts to form (see diagram below).

Complex reactions, on the other hand, occur through a series of steps. An example is the acid-catalysed iodination of propanone:

The rate of the reaction depends on the concentration of two species but, surprisingly, does not depend on the concentration of iodine:

The mechanism of the reaction consists of four steps, each with a particular reaction rate (see diagram below).

The overall rate of reaction is dependent on the slowest step, which is called the rate determining step. As the rate determining step for the above reaction is the rearrangement of the first intermediate CH3C(OH)CH3+ to the second intermediate CH3C(OH)CH2, the proposed rate law is:

However, in chemical kinetics, we are interested in analysing the effect of varying concentrations of reactants on the rate of the reaction. Therefore, we modify eq43 to reflect the concentrations of reactants by noting that

-

- k2 « k-1, such that we assume [CH3C(OH)CH3+] attains a constant value before the conversion of CH3C(OH)CH3+ to CH3C(OH)CH2 commences.

- The forward and reverse rates for the first step are equal at equilibrium and hence:

Substitute eq44 in eq43

which is eq42.

An energy profile diagram of this reaction (see diagram above) shows four activated complexes with energies coinciding with the peaks (denoted by green dots) and three intermediates with potential energies matching the three troughs of the curve (denoted by red dots). It is important to note that an intermediate is a relative stable and isolable chemical species that exists for a finite time, while an activated complex is an unstable, non-isolable chemical structure that has only a transient existence.

Question

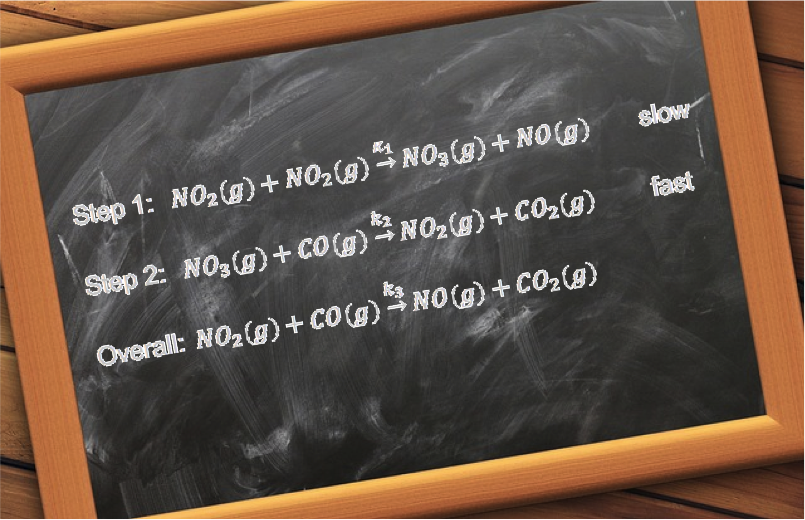

Propose a two-step mechanism for the reaction , which has the experimentally observed rate law:

.

Answer

The rate determining step must involve O2 or NO or both. Let’s suppose it is the final step of the mechanism and has O2 as a reactant:

where M is an unknown intermediate molecule.

This implies that the preceding step is possibly:

Balancing the above equations reveals the intermediate as: N2O2 . To check whether the proposed mechanism is reasonable, we write the rate law for the rate determining step:

If we assume k2 « k-1 such that [N2O2] attains a constant value before it reacts with O2, we can substitute the equilibrium expression of in eq45 to give:

To further validate the proposed mechanism, we need to isolate the intermediate.