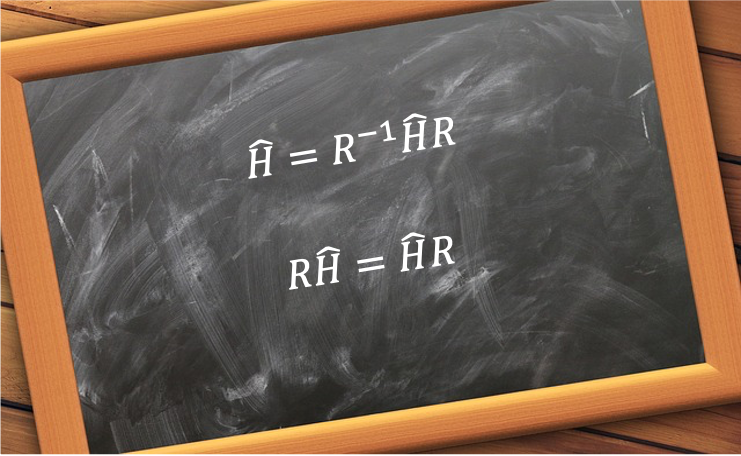

Symmetry and degeneracy are related as a result of the non-relativistic Hamiltonian  being invariant under symmetry operations.

being invariant under symmetry operations.

Consider the stationary state of a quantum mechanical system that is described by a set of linearly independent wavefunctions  , which satisfies the time-independent Schrodinger equation

, which satisfies the time-independent Schrodinger equation  . Subjecting both sides of the equation to the symmetry operation

. Subjecting both sides of the equation to the symmetry operation  , where

, where  are elements of a group

are elements of a group  , we have

, we have  . Using eq53 and noting that

. Using eq53 and noting that  is a scalar, we obtain

is a scalar, we obtain

which implies that  is an eigenfunction of

is an eigenfunction of  , i.e.

, i.e.  .

.

We say that the set of symmetry operations form the group of the Hamiltonian. If  is

is  -fold degenerate, any linear combination of the subset of wavefunctions

-fold degenerate, any linear combination of the subset of wavefunctions  associated with the degenerate eigenvalue will be a solution of eq54. We can then write:

associated with the degenerate eigenvalue will be a solution of eq54. We can then write:

According to the closure property of  ,

,

So,

Since  is a linear operator,

is a linear operator,

Subtracting eq59 from eq57, we have \psi_m=0) . If the wavefunctions are linearly independent, all coefficients of

. If the wavefunctions are linearly independent, all coefficients of  must be zero, i.e.

must be zero, i.e.

With reference to eq55 through eq57,  and

and  range from

range from  to

to  . Thus, eq60 implies that

. Thus, eq60 implies that  and

and  are entries of the square matrices

are entries of the square matrices  and

and  respectively, i.e.

respectively, i.e.

Comparing eq61 with eq58, the matrices  and

and  multiply the same way as the symmetry operations

multiply the same way as the symmetry operations  and

and  and therefore form a representation

and therefore form a representation  of

of  . Such a representation has a dimension equal to

. Such a representation has a dimension equal to  and may be reducible or irreducible. However, the following analysis shows that it is irreducible, assuming that there is no accidental degeneracy, which happens when two eigenvalues are the same even though their corresponding eigenfunctions transform differently under the symmetry operations of

and may be reducible or irreducible. However, the following analysis shows that it is irreducible, assuming that there is no accidental degeneracy, which happens when two eigenvalues are the same even though their corresponding eigenfunctions transform differently under the symmetry operations of  .

.

To show that  is irreducible, we express eq55 as

is irreducible, we express eq55 as

where  .

.

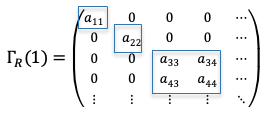

If  is reducible, then it may be in block-diagonal form. For example, if

is reducible, then it may be in block-diagonal form. For example, if  ,

,

Substituting eq61b in eq61a,  and

and  are linear combinations of the subset with elements

are linear combinations of the subset with elements  and

and  , while

, while  and

and  are linear combinations of the subset with elements

are linear combinations of the subset with elements  and

and  . If so, the eigenvalues corresponding to the different subsets could be different (e.g. when one subset is one-dimensional and the other is two-dimensional), which would contradict our original assumption that

. If so, the eigenvalues corresponding to the different subsets could be different (e.g. when one subset is one-dimensional and the other is two-dimensional), which would contradict our original assumption that  is

is  -fold degenerate.

-fold degenerate.

If  is not initially in block-diagonal form, it can be converted into a block-diagonal matrix

is not initially in block-diagonal form, it can be converted into a block-diagonal matrix  via a similarity transformation, where

via a similarity transformation, where  . We can then rewrite eq61a as

. We can then rewrite eq61a as

where  is the basis for the transformed representation.

is the basis for the transformed representation.

Since  is in block-diagonal form, we arrive at the same conclusion as before. Therefore, assuming that there is no accidental degeneracy, a representation that is generated by a set of orthogonal degenerate wavefunctions is irreducible and we called the set of wavefunctions

is in block-diagonal form, we arrive at the same conclusion as before. Therefore, assuming that there is no accidental degeneracy, a representation that is generated by a set of orthogonal degenerate wavefunctions is irreducible and we called the set of wavefunctions  , basis wavefunctions of

, basis wavefunctions of  .

.

Question

1) Why is the number of basis functions needed to generate  equal to the dimension of

equal to the dimension of  ?

?

2) Can any set of functions, other than eigenfunctions of the Hamiltonian, be a set of basis functions for a representation of  ?

?

3) Show that if  is a basis of a representation

is a basis of a representation  of a group, then any linear combination of

of a group, then any linear combination of  is a basis of a representation

is a basis of a representation  that is equivalent to

that is equivalent to  .

.

Answer

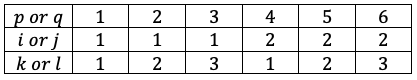

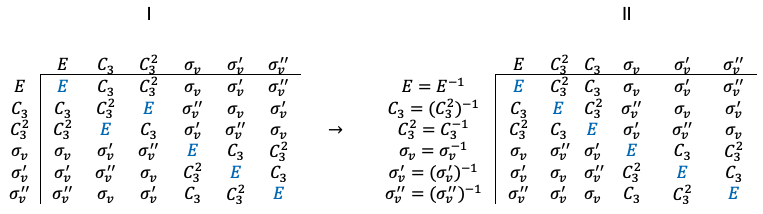

1) Each  in

in  of eq55 creates a column of matrix entries

of eq55 creates a column of matrix entries  (see Q&A below for an illustration). So, the

(see Q&A below for an illustration). So, the  matrix

matrix  is generated by

is generated by  number of

number of  . The same logic applies to matrices

. The same logic applies to matrices  and

and  . This implies that the number of linearly independent basis functions of a representation corresponds to the dimension of the representation. This set of linearly independent basis functions can be made orthogonal to one another using the Gram-Schmidt process. Therefore, the number of orthogonal basis functions of a representation corresponds to the dimension of the representation.

. This implies that the number of linearly independent basis functions of a representation corresponds to the dimension of the representation. This set of linearly independent basis functions can be made orthogonal to one another using the Gram-Schmidt process. Therefore, the number of orthogonal basis functions of a representation corresponds to the dimension of the representation.

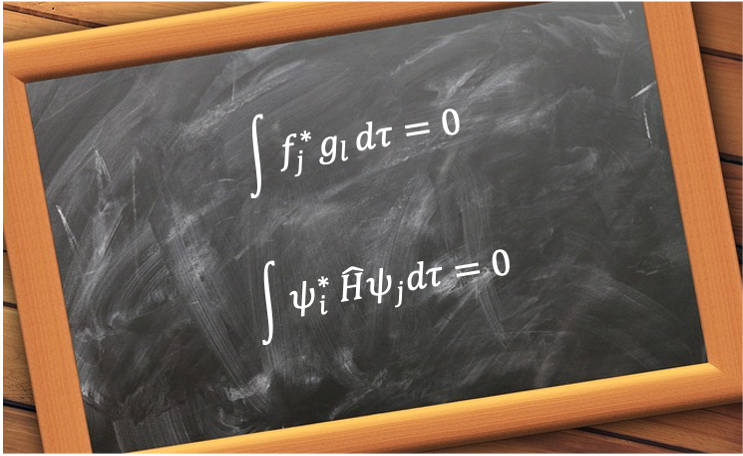

2) By inspecting eq55 through eq61, any set of linearly independent functions  , not necessary eigenfunctions of the Hamiltonian, is a set of basis functions for a representation of

, not necessary eigenfunctions of the Hamiltonian, is a set of basis functions for a representation of  if

if  is transformed by a symmetry operation into a linear combination of

is transformed by a symmetry operation into a linear combination of  . The converse is obviously also true, i.e. if

. The converse is obviously also true, i.e. if  is a set of basis functions for a representation of

is a set of basis functions for a representation of  , then

, then  . In this case, there is no requirement that the functions are degenerate and hence the representation generated can be either reducible or irreducible.

. In this case, there is no requirement that the functions are degenerate and hence the representation generated can be either reducible or irreducible.

3) Since matrix multiplication is distributive,

Let’s rewrite eq55 as  . Substituting this expression in the above equation and rearranging, gives

. Substituting this expression in the above equation and rearranging, gives

where  .

.

Using eq61d and repeating the steps from eq55 through eq61,  is also basis of a representation

is also basis of a representation  of the group.

of the group.

To Show that  is equivalent to

is equivalent to  , let

, let  , which can be written as the following matrix equation:

, which can be written as the following matrix equation:

where  .

.

Using eq55 with  in place of

in place of  , we have

, we have  , whose matrix equation is

, whose matrix equation is

where  .

.

Multiplying eq61e by  on the right, we have

on the right, we have  , which when substituted in eq61f gives

, which when substituted in eq61f gives

The matrix equation of eq55 with  in place of

in place of  is

is

Comparing eq61g with eq61h, ) is related to

is related to ) by a similarity transformation. This implies that

by a similarity transformation. This implies that  is equivalent to

is equivalent to  .

.

If  is non-degenerate, the only eigenfunctions satisfying eq54 are

is non-degenerate, the only eigenfunctions satisfying eq54 are  , where

, where  is a constant. Therefore,

is a constant. Therefore,  . Normalising

. Normalising  , we get

, we get  , which means that

, which means that  . Consequently, the wavefunctions

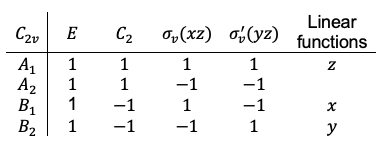

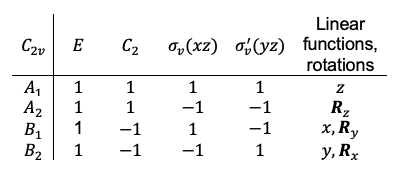

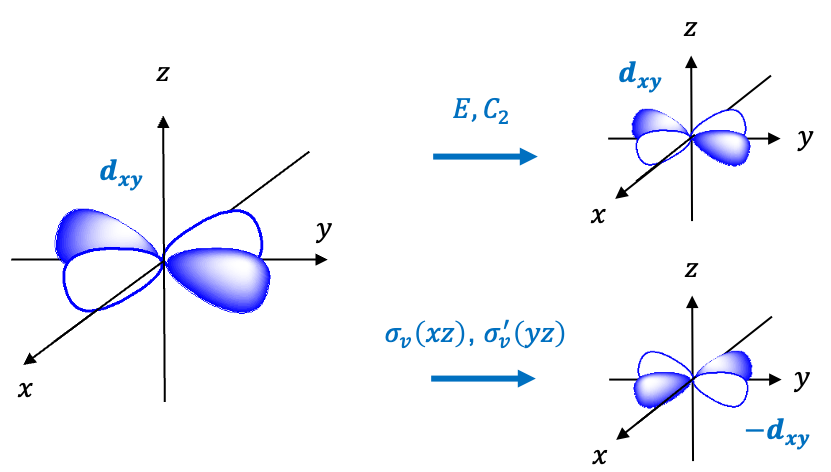

. Consequently, the wavefunctions  associated with non-degenerate eigenvalues transform according to one-dimensional irreducible representations with characters of +1 or -1.

associated with non-degenerate eigenvalues transform according to one-dimensional irreducible representations with characters of +1 or -1.

Question

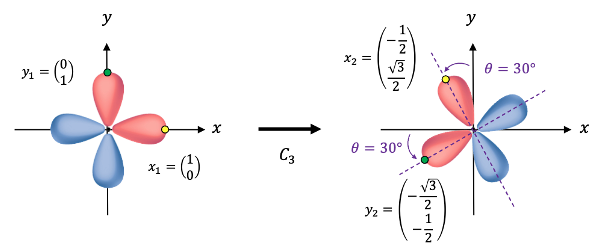

If  , show how eq55 is related to the matrix representation

, show how eq55 is related to the matrix representation ) .

.

Answer

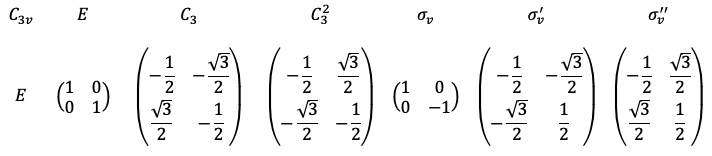

The two degenerate wavefunctions are  and

and  . We have

. We have

=\begin{pmatrix}a_{11}&a_{12}\\a_{21}&a_{22}\end{pmatrix})

We can conclude from the above analysis that irreducible representations with dimension of one are called non-degenerate representations, while those with dimensions of more than one are known as degenerate representations.

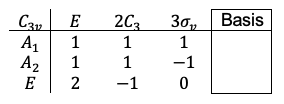

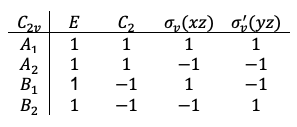

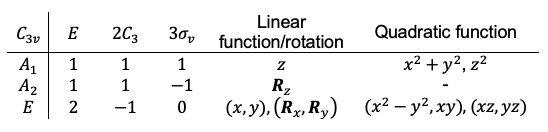

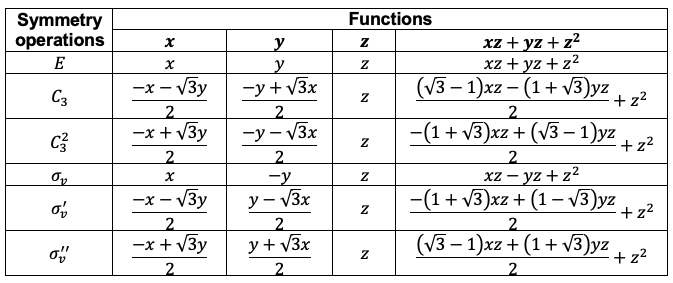

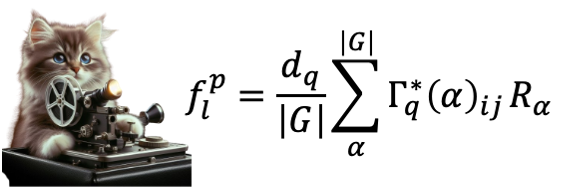

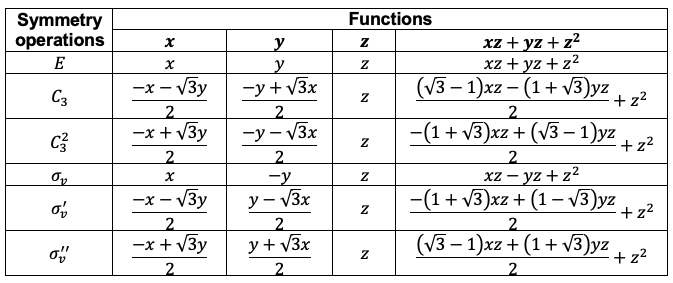

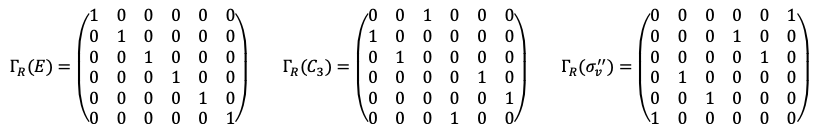

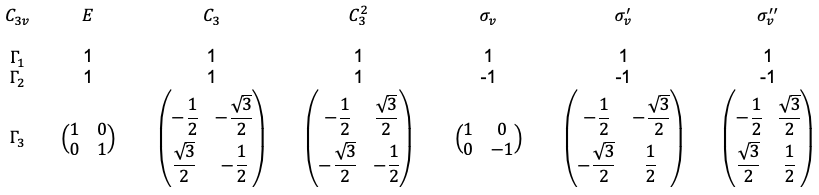

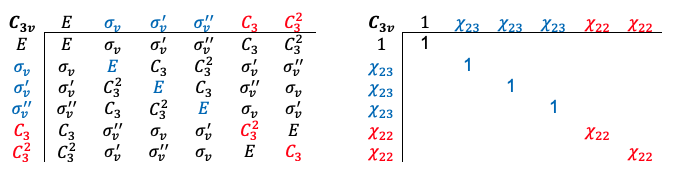

Repeating the same procedure shown in the Q&A above for the rest of the symmetry operations of the  point group, we have

point group, we have

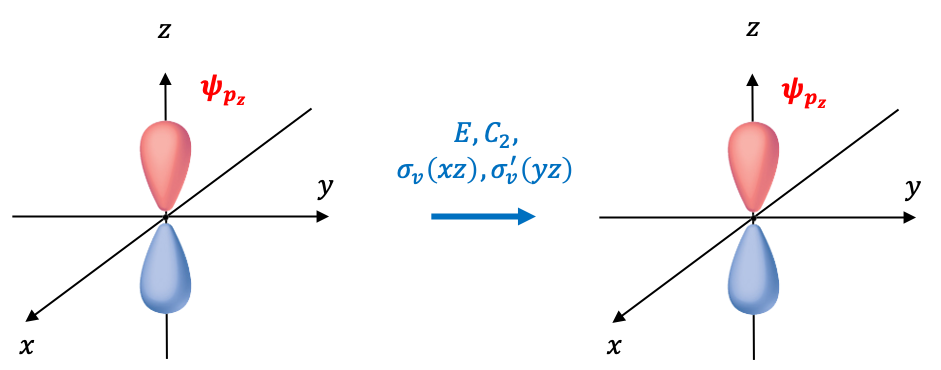

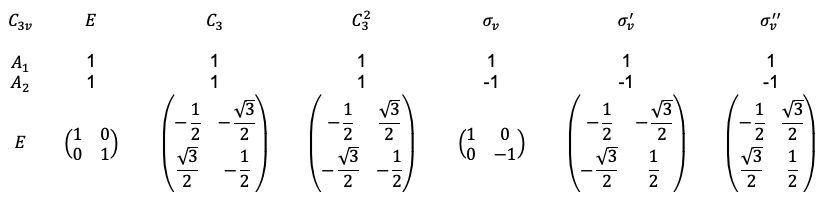

The transformation of the function  is determined by summing the separate transformations of the

is determined by summing the separate transformations of the  -orbitals

-orbitals  and

and  .

.

and

, resulting in

, we have

and

.

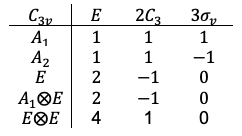

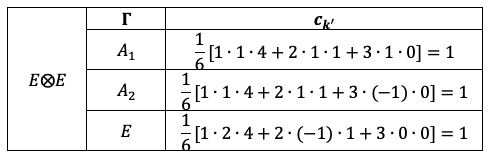

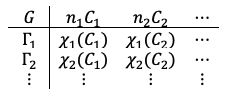

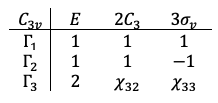

is the number of classes.

is the number of elements in the

-th class.

, called the character of a class, is the trace of a matrix belonging to the

-th class of the

-th irreducible representation.

and

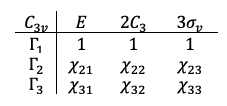

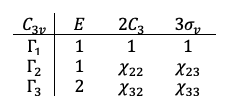

of the

point group are reducible or irreducible.

is an irreducible representation of the

point group, while

is a reducible representation of the

point group.

and

in a

-dimensional vector space, with components

and

respectively. The components are functions of

and the two vectors are orthogonal to each other when

. A

-dimensional vector space is spanned by

orthogonal vectors, each with

components. Since the number of vectors and the number of components of each vector are denoted by

and

respectively, the number of irreducible representations of a group is equal to the number of classes of that group. We say that the irreducible representations of a group form a complete set of basis vectors in the

-dimensional vector space, with the components of each basis vector being

.

and

with entries

and

respectively.

are given by:

and

are square matrices and

, then

, i.e.

and

are square matrices and

, then

.

and

, we have

, which implies that

and

are not zero and are therefore non-singular. So,

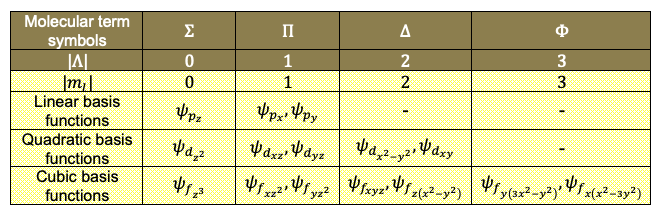

The use of molecular term symbols in character tables have useful applications in spectroscopy.

The use of molecular term symbols in character tables have useful applications in spectroscopy.