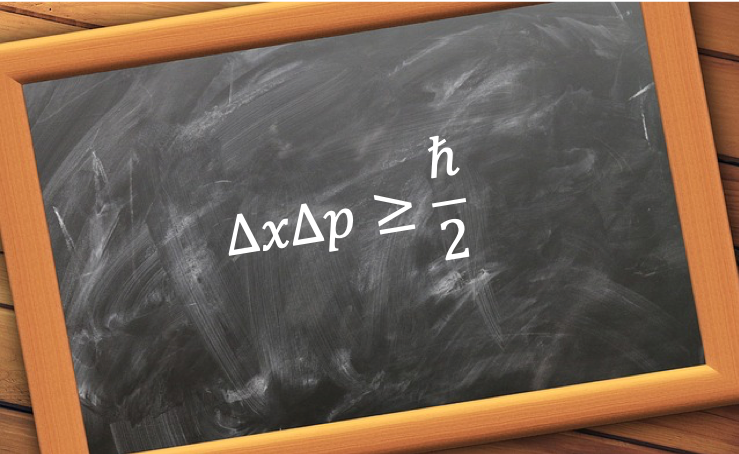

Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle states that the position and momentum of a particle cannot be determined simultaneously with unlimited precision.

The uncertainty not only applies to the position and momentum of a particle, but to any pair of complementary observables, e.g. energy and time. In general, the uncertainty principle is expressed as:

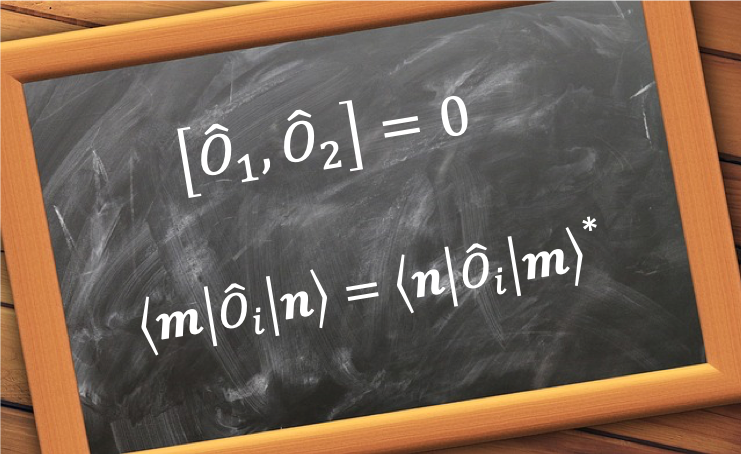

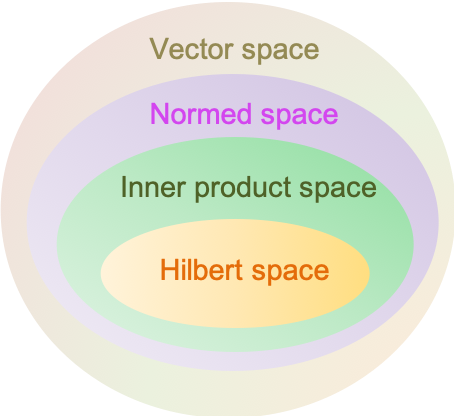

where and

are Hermitian operators and

and

are their respective observables.

The derivation of eq12 involves the following:

- Deriving the Schwarz inequality

- Proving the inequality

- Showing that

Step 1

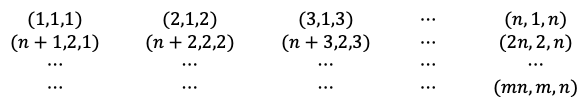

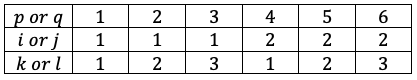

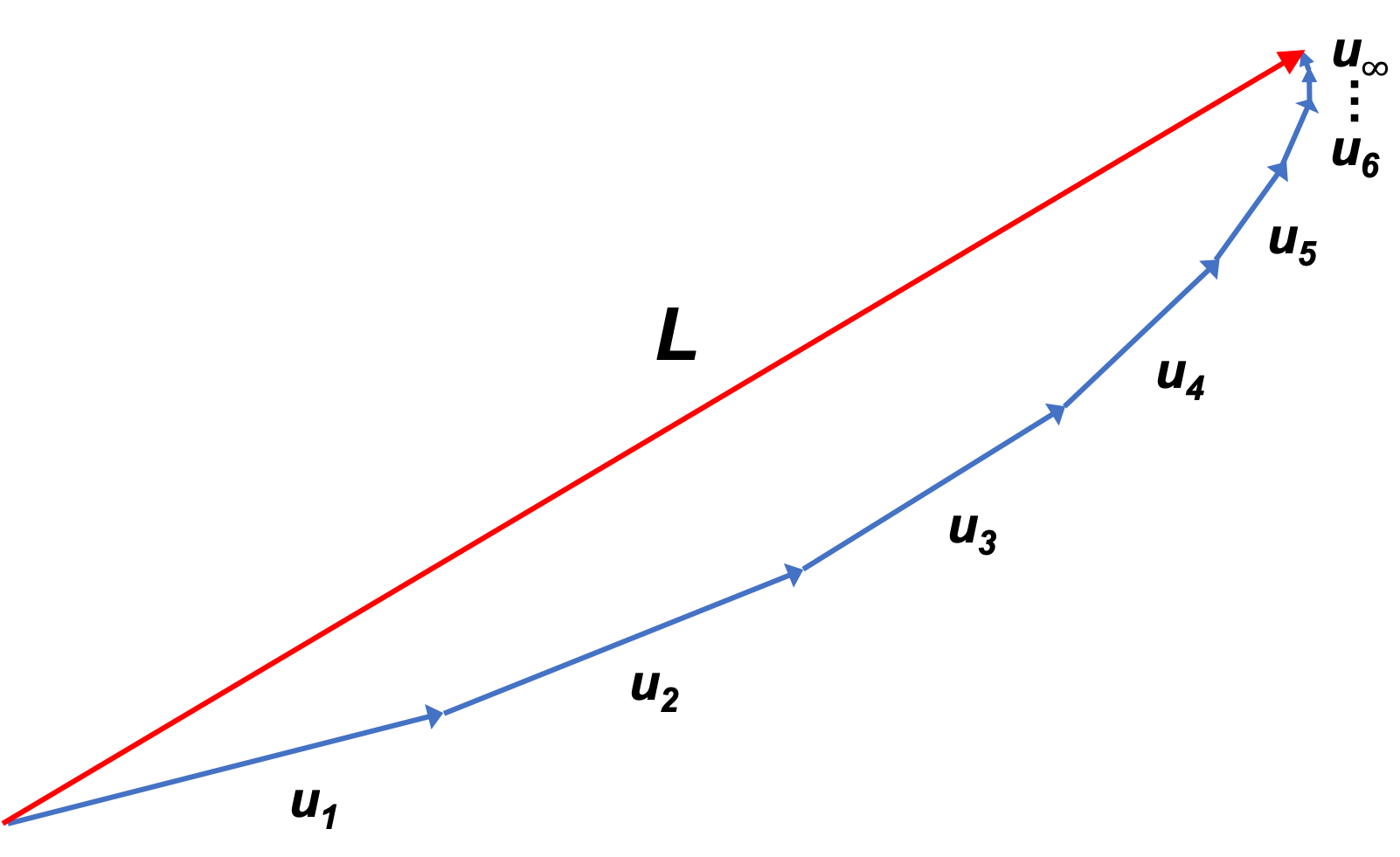

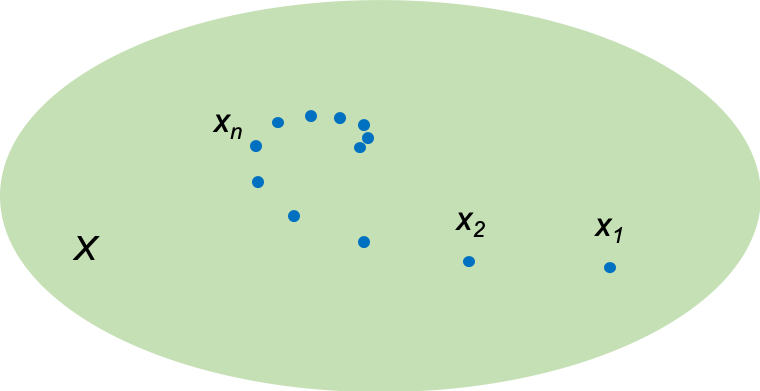

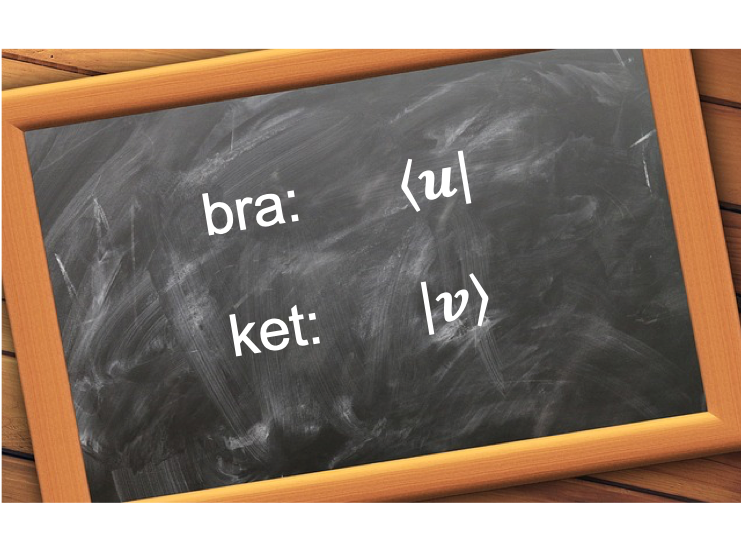

Let

where and

are arbitrary square integrable wavefunctions and

is an arbitrary scalar.

Since

Expanding eq13, we have

Since is an arbitrary scalar, substituting

and

in eq15 gives:

Substituting eq14 in the above equation and rearranging yields . Since

Eq16 is called the Schwarz Inequality.

Step 2

Let and

, where

is normalised, and

and

are Hermitian operators, which implies that

and

are also Hermitian operators (see this article for proof). The variance of the observable of

is

Note that the 2nd last equality uses the property of Hermitian operators (see eq36). Similarly,

Substituting eq17 and eq18 in eq16 results in

Let where

. So,

. Since

, we have

, which is

Substituting eq19 in eq20 gives

Next, we have

Similarly,

Substituting eq22 and eq23 in eq21 yields

Step 3

We have used eq37 for the 2nd equality and eq35 for the 3rd equality. Substituting eq25 in one of the in eq24 results in

Therefore,

which is eq12, the general form of the uncertainty principle.

For, the observable pair of position and momentum

, we have

Since