The postulates of quantum mechanics are fundamental mathematical statements that cannot be proven. Nevertheless, they are statements that everyone agrees with.

Examples of other postulates of science and mathematics are Newton’s 2nd law,  , and the Euclidean statement that a line is defined by two points respectively.

, and the Euclidean statement that a line is defined by two points respectively.

Generally, the postulates of quantum mechanics are expressed as the following 7 statements:

1) The state of a physical system at a particular time  is represented by a vector in a Hilbert space.

is represented by a vector in a Hilbert space.

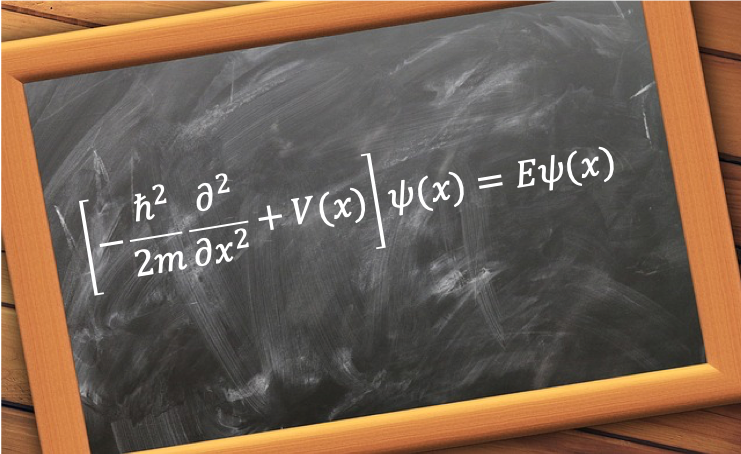

We call such a vector, a wavefunction ) , which is a function of time and space . A wavefunction contains all assessable physical information about a system in a particular state. For example, the energy of the stationary state of a system is obtained by solving the time-independent Schrodinger equation

, which is a function of time and space . A wavefunction contains all assessable physical information about a system in a particular state. For example, the energy of the stationary state of a system is obtained by solving the time-independent Schrodinger equation  .

.

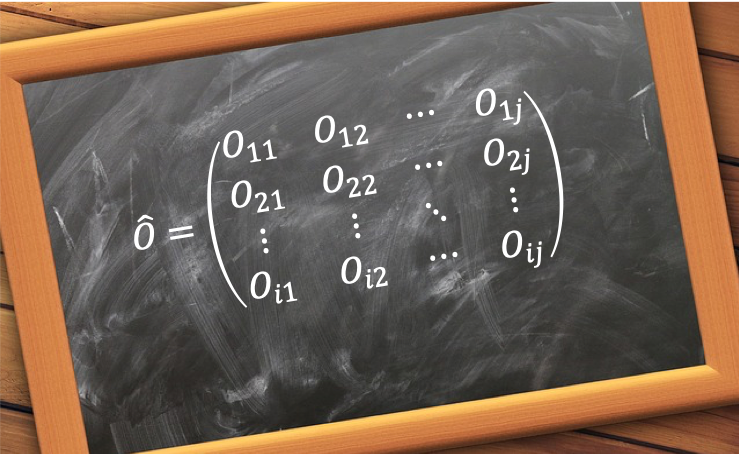

2) Every measurable physical property of a system is described by a Hermitian operator  that acts on a wavefunction representing the state of the system.

that acts on a wavefunction representing the state of the system.

In other words, to every observable quantity in classical mechanics there corresponds a linear, Hermitian operator in quantum mechanics. The most well-known Hermitian operator in quantum mechanics is the Hamiltonian  , which is the energy operator. The wavefunctions that

, which is the energy operator. The wavefunctions that  acts on are called eigenfunctions. Eigenfunctions of a Hermitian operator in quantum mechanics are further postulated to form a complete set. Other Hermitian operators frequently encountered in quantum mechanics are the momentum operator

acts on are called eigenfunctions. Eigenfunctions of a Hermitian operator in quantum mechanics are further postulated to form a complete set. Other Hermitian operators frequently encountered in quantum mechanics are the momentum operator  and the position operator

and the position operator  .

.

3) The result of the measurement of a physical property of a system must be one of the eigenvalues of an operator  .

.

The state of a system is expressed as a wavefunction, which can be a single basis wavefunction or a linear combination of a complete set of basis wavefunctions. Since basis wavefunctions of a Hermitian operator form a complete set, all wavefunctions can be written as a linear combination of basis wavefunctions.

Question

What about a system described by a stationary state?

Answer

The wavefunction can be expressed, though trivially, as  , where

, where  and

and  (we have assumed that the spectrum is discrete, i.e. the eigenvalues are separated from one another).

(we have assumed that the spectrum is discrete, i.e. the eigenvalues are separated from one another).

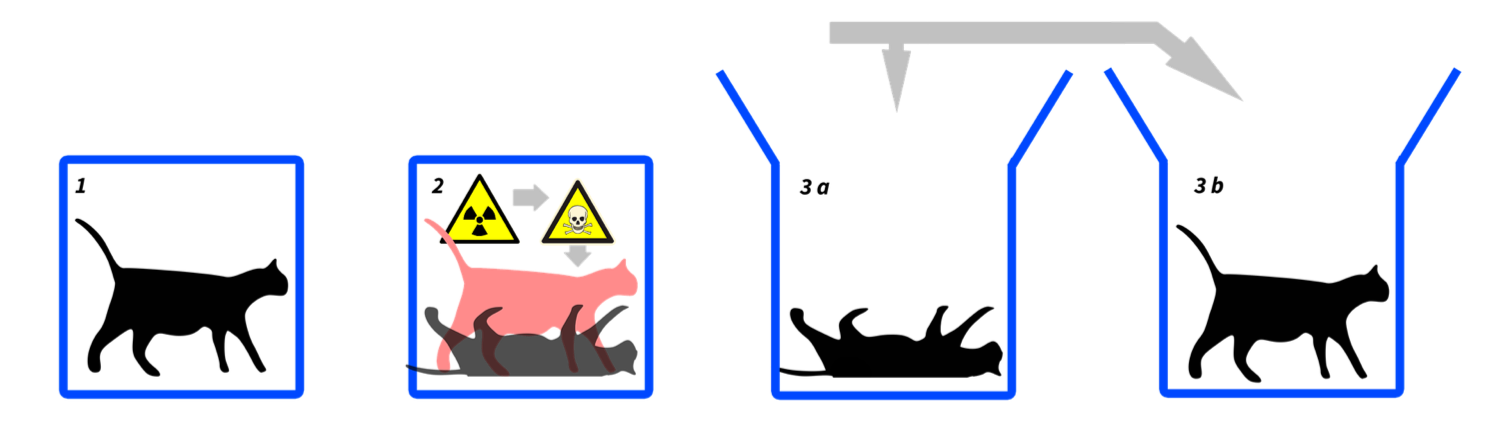

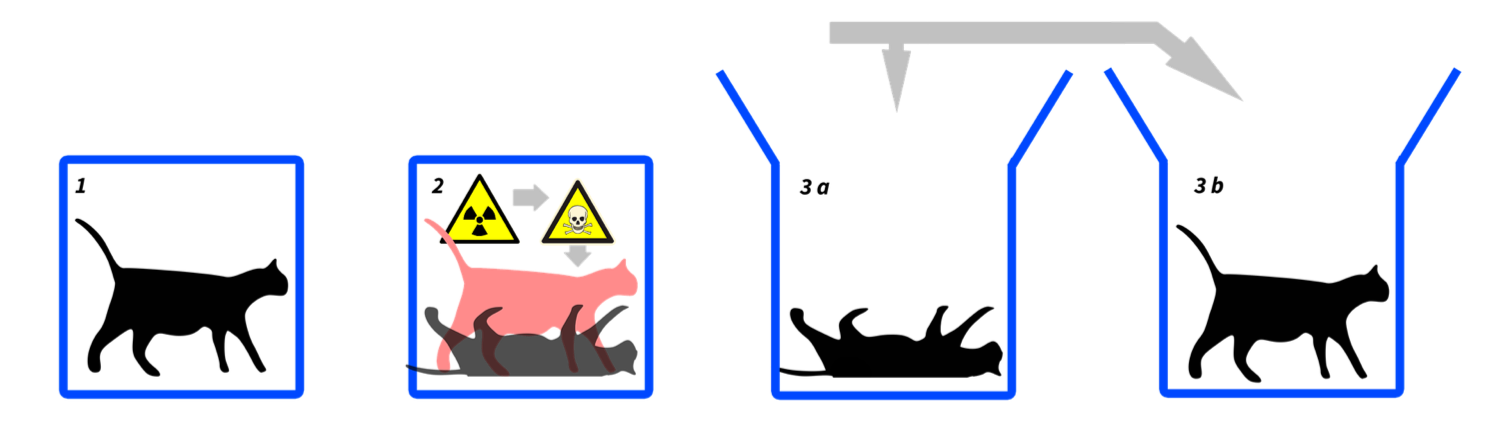

It is generally accepted by scientists that the values of the coefficients  are unknown prior to a measurement. Upon measurement, the result obtained is an eigenvalue associated with one of the eigenfunctions, and hence the phrase ‘the initial wavefunction collapses to one of the eigenfunctions’. This implies that the measurement alters the initial wavefunction such that a 2nd measurement, if made quickly, yields that same result (this obviously refers to wavefunctions describing non-stationary states, as wavefunctions of stationary states are independent of time). If we prepare a large number of identical systems and simultaneously measure them, the values of

are unknown prior to a measurement. Upon measurement, the result obtained is an eigenvalue associated with one of the eigenfunctions, and hence the phrase ‘the initial wavefunction collapses to one of the eigenfunctions’. This implies that the measurement alters the initial wavefunction such that a 2nd measurement, if made quickly, yields that same result (this obviously refers to wavefunctions describing non-stationary states, as wavefunctions of stationary states are independent of time). If we prepare a large number of identical systems and simultaneously measure them, the values of  are found; with

are found; with  , and the expectation value of the measurements being

, and the expectation value of the measurements being  .

.

4) The probability of obtaining an eigenvalue  upon measuring a system is given by the square of the inner product of the normalised

upon measuring a system is given by the square of the inner product of the normalised  with the orthonormal eigenfunction

with the orthonormal eigenfunction  .

.

In other words,

If the spectrum is continuous,  and the probability of obtaining an eigenvalue in the range

and the probability of obtaining an eigenvalue in the range  is

is  .

.

5) The state of a system immediately after a measurement yielding the eigenvalue  is described by the normalised eigenfunction

is described by the normalised eigenfunction  .

.

We have explained in the postulate 3 that this is commonly known as the collapse of the wavefunction  to one of the eigenfunctions

to one of the eigenfunctions  . It is also known as the projection of

. It is also known as the projection of  onto

onto  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  ; or if

; or if  is not normalised:

is not normalised:

Question

Show that  is the normalisation constant.

is the normalisation constant.

Answer

To normalise a wavefunction,

So,

^{*}}})

6) The time evolution of the wavefunction ) is governed the time-dependent Schrodinger equation

is governed the time-dependent Schrodinger equation \rangle=\hat{H}(t)\vert\psi(t)\rangle) .

.

7) The total wavefunction of a system of identical particles must be either symmetric (for bosons) or antisymmetric (for fermions) under exchange of any two particles. This postulate is often referred to as the symmetrisation postulate.

in spherical coordinates can be derived from eq87, eq88 and eq89. Substituting eq78 through eq86 in eq87, eq88 and eq89, adding the resulting three equations and simplifying, we have

is constant and

. The first term of the Laplacian operating on a wavefunction

will return a result of zero. We can therefore discard it and eq48 becomes:

.

is the energy associated with the angular motion of a particle. This implies that the linear (or radial) part of the Hamiltonian is:

is the energy associated with the linear motion of a particle. We can, therefore, rewrite eq48 as: