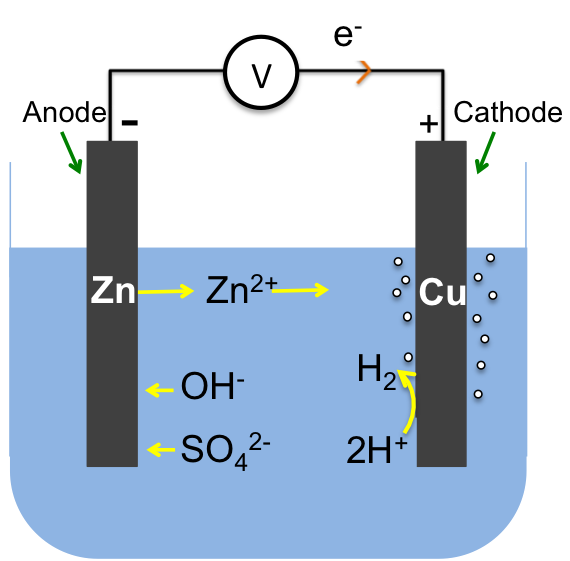

To analyse reactions in an electrochemical cell, for example the Zn–Cu cell, we follow these steps:

Step 1: Determine the direction of flow of electrons (to identify the oxidation reaction) by

-

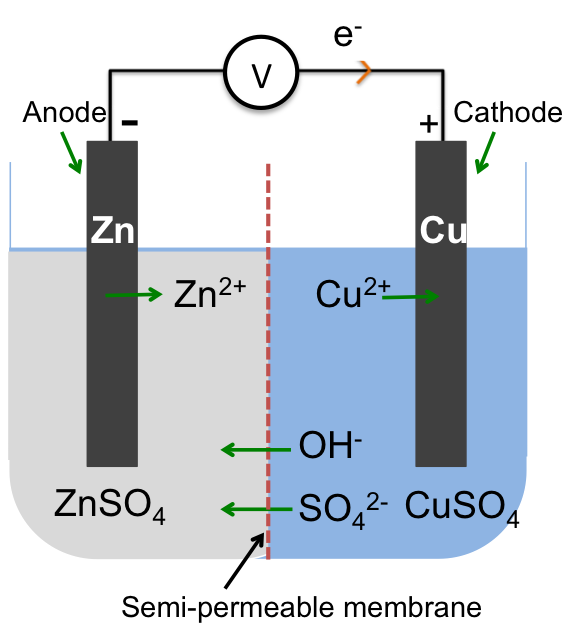

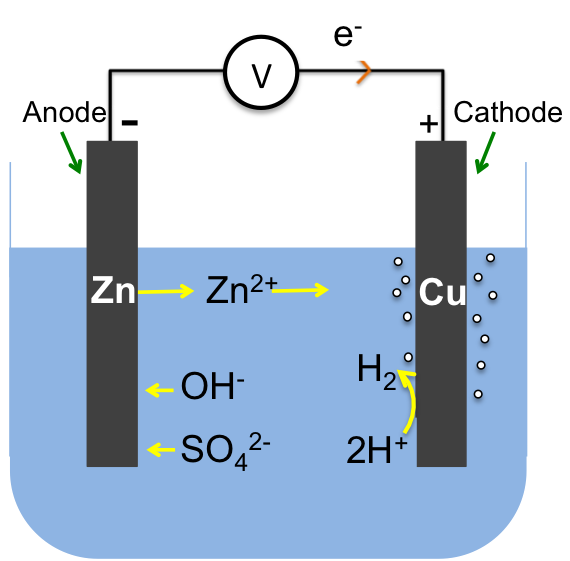

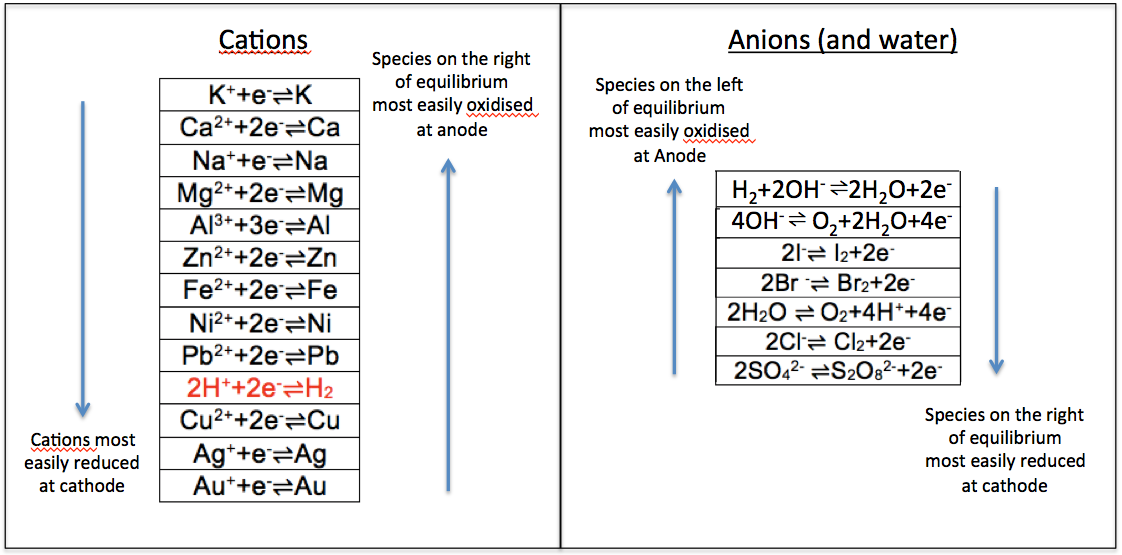

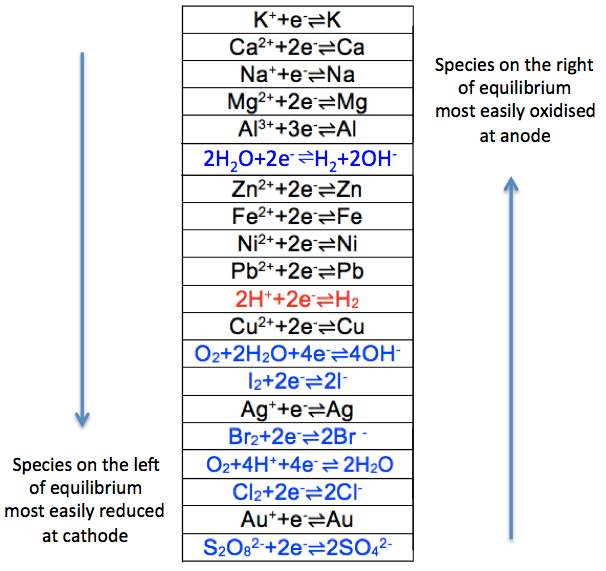

- Finding the possible reactants in the electrochemical cell: Zn, Cu, H+, SO42– and H2O (note that H2O is always assumed to be the species instead of OH– in non-hydroxide aqueous solutions, as the concentration of OH– from H2O is very small).

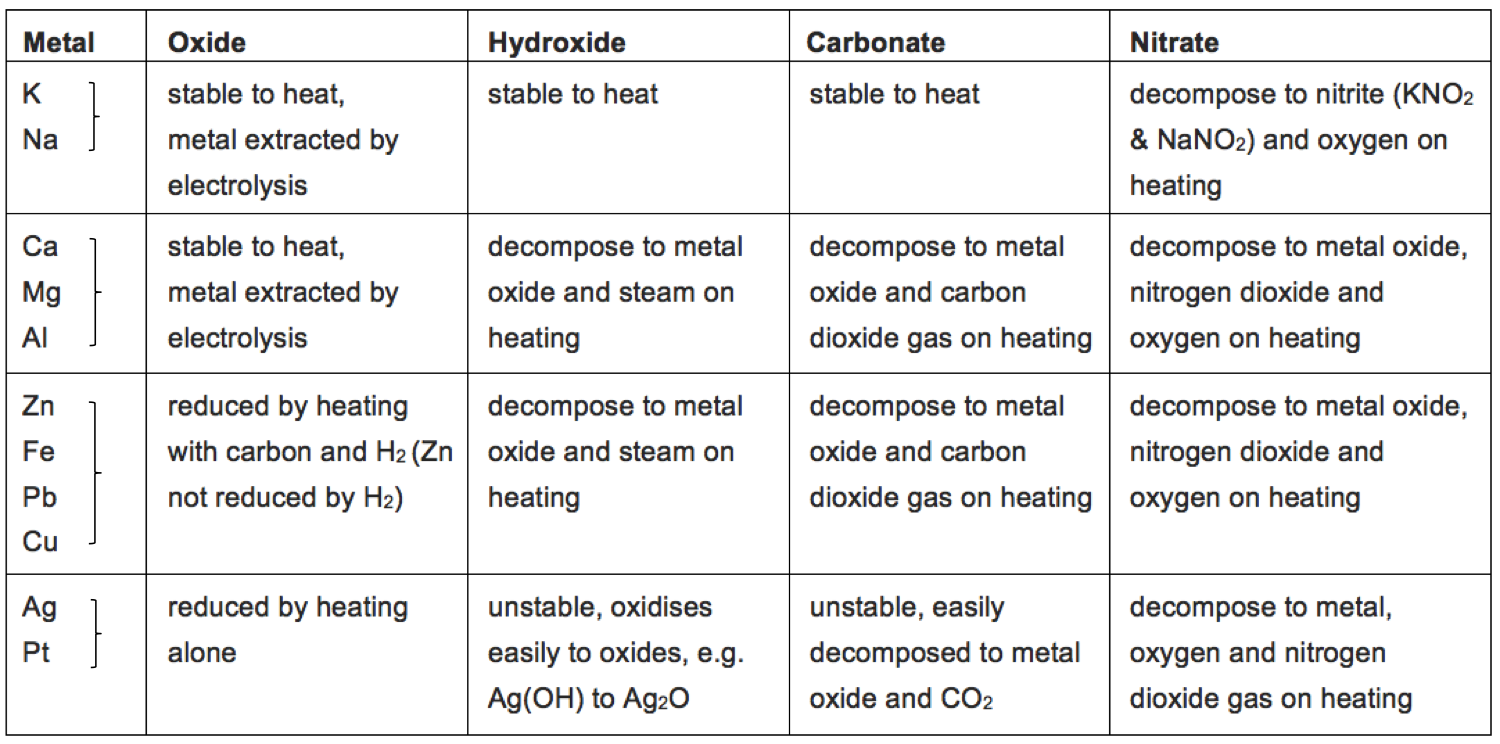

- Distinguishing the most reactive species according to the electrochemical series: Zn

- Writing the ionic half-reaction equation for the most reactive species, which undergoes oxidation:

Zn (s) → Zn2+ (aq) + 2e–

Zinc, being most reactive amongst all the species in the electrochemical cell, is oxidised with free electrons flowing from the anode (zinc electrode) to the cathode (copper electrode). The electrons, upon reaching the cathode, preferentially reduce one of the species at the electrode’s surface.

Step 2: Identify the reduction reaction at the cathode by

-

- Finding all possible reducible species (usually cations): Zn2+, H2O and H+.

- Distinguishing the species that is most readily reduced, if there is more than one competing species, by:

- comparing the species on the electrochemical series: H+.

- comparing the concentrations of the species if their positions in electrochemical series are relatively close to one another: Zn2+ and H2O are relatively far apart in the series from H+, so the result is still H+.

- Writing the ionic half-reaction equation for the reduction reaction:

2H+ (aq) + 2e– → H2 (g)

Combining the two half reaction equations, the overall redox reaction in the electrochemical cell is:

Zn (s) + 2H+ (aq) → Zn2+ (aq) + H2 (g)

A potential difference is established between the two electrodes as a result of the redox reaction, and its magnitude (voltage) is measured by the voltmeter attached to the wire.

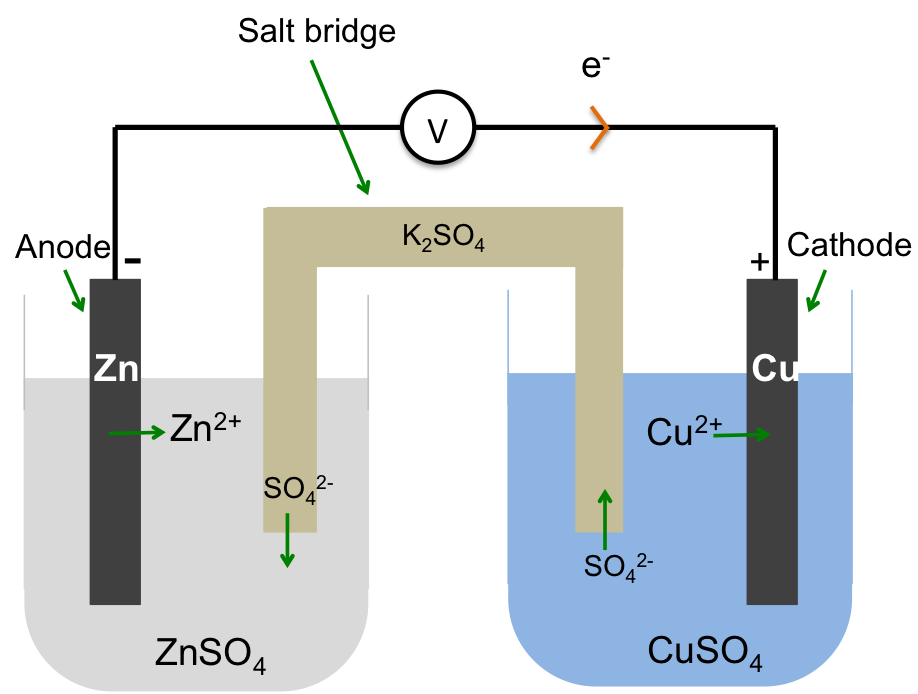

If we perceive the electrolyte as the chemical in a battery, the electrodes as terminals of the battery and the voltmeter as the external load, we can label the anode as negative and the cathode as positive since current (opposite direction to the flow of electron) flows from the positive terminal of a battery to the negative terminal. Note that the electrochemical circuit is complete by the flow of electrons from the anode to the cathode via the wire and a net flux of negative ions towards the anode and positive ions towards the cathode in the electrolyte.

Question

Why is the voltmeter not connected parallel to a load in the circuit?

Answer

By connecting the voltmeter in series, we are measuring the potential difference of an open circuit with almost no current flowing. This is an accurate way to measure the potential difference, as it allows the concentration of the electrolytes to remain unchanged. To understand more about the effects of the flow of a current on the potential of an electrochemical cell, read the article on overpotential in the advanced section.