The linear Stark effect is the splitting or shifting of atomic or molecular energy levels in proportion to the strength of an applied electric field.

It is defined as the first-order energy correction in perturbation theory and is most clearly observed in hydrogenic atoms, where the high symmetry of the Coulomb potential leads to degeneracies that allow first-order shifts. In the strong-field regime ( V/m), where the static, uniform electric field strength

produces energy shifts that are large compared to those arising from spin-orbit interactions, the Hamiltonian

for a hydrogenic atom is:

where is the Hamiltonian of the unperturbed atom and

is the perturbation due to the Stark effect.

The perturbing Hamiltonian is given by eq354:

where is the operator of the electric dipole moment of the atom.

This suggests that vanishes if the electric dipole operator is zero. Substituting eq350 into

gives

where is the operator of the position vector

of the electron, with the vector measured from the nucleus (taken as the origin).

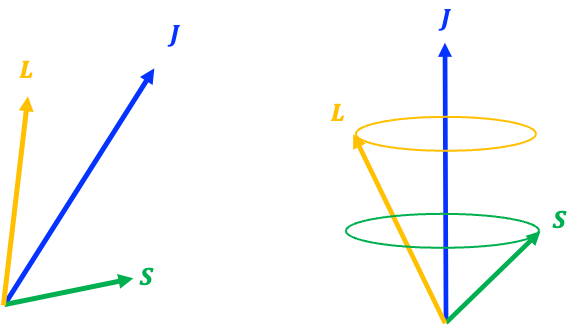

Compared to the Zeeman Hamiltonian, which depends on both the orbital and spin angular momenta of the electron, the Stark Hamiltonian depends only on and therefore acts only on the spatial part of the hydrogenic wavefunction.

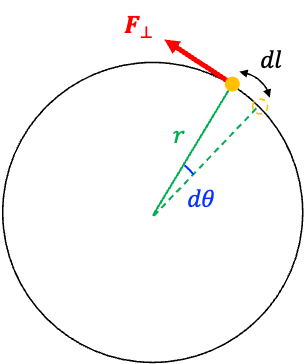

Assuming that the electric field is directed along the laboratory -axis, eq361 becomes

where is the angle between

and the

-axis.

To understand how the perturbation affects the energy levels, we analyse its effect on the and

states of the atom. The uncoupled wavefunction

, which is a good eigenstate of

, is used as a basis to begin the perturbation analysis. For

, the eigenstate

is the non-degenerate ground state

. Therefore, we may apply the first-order non-degenerate perturbation theory, which corresponds to the expectation value of

:

or equivalently, in spherical coordinates,

Since , we have

. Therefore, the ground state of a hydrogenic atom exhibits no first-order Stark effect, as its spherical symmetry implies that it possesses no permanent electric dipole moment. In fact, because

is odd under spatial inversion (it changes sign about the origin), its expectation value vanishes for any eigenstate of even parity, since the integral of an odd function multiplied by an even function over all space is zero.

Unlike the ground state, the unperturbed level is fourfold degenerate described by the following basis wavefunctions (see this article and this article for derivation):

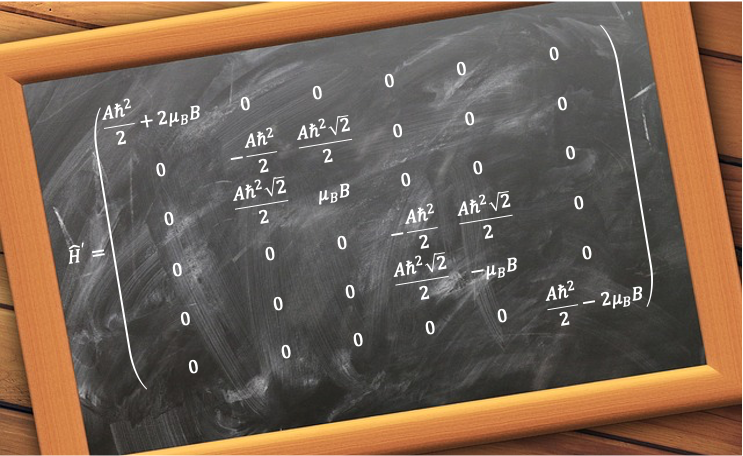

Due to this degeneracy, we must use degenerate perturbation theory, which requires constructing the Stark Hamiltonian matrix with elements

. Because

has even parity and

is odd under spatial inversion, all diagonal matrix elements vanish:

Furthermore, the matrix elements ,

,

,

and

, together with their complex conjugates, are all zero because their corresponding azimuthal integrals involve terms such as

,

or

, all of which vanish. This leaves

and its complex conjugate

, each of which evaluates to

.

Therefore, we need to solve the eigenvalue equation

where ,

,

and

are the coefficients in the basis

and

To find the eigenvalues, we solve the secular equation or equivalently,

Evaluating the determinant gives the characteristic equation:

with solutions:

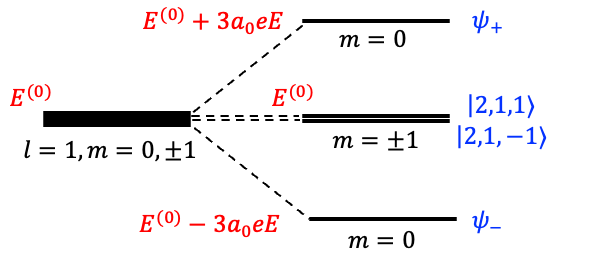

Therefore, the fourfold degenerate level is split by the Stark effect into three distinct levels (see diagram below):

,

and

, where

is the eigenvalue of the unperturbed Hamiltonian

.

To determine the eigenstates corresponding to the three distinct levels, we refer to eq364, where

For , we require

and

. Since there are no conditions on

or

, any linear combination of

and

is an eigenstate with eigenvalue 0. However, a state

, with both

and

, is not an eigenstate of

(i.e.

is not well-defined). Therefore, only the linear combinations in which either

or

, namely the unmixed states

or

, are good eigenstates of both

and

for

.

For , eq366 gives the condition

and

. Hence, the normalised eigenstate is

Similarly, for , the same equation yields

and

resulting in the normalised eigenstate

Since both and

are eigenstates of

, each with eigenvalue

,

and

remain eigenstates of

. However,

and

are no longer eigenstates of

, meaning

is not a good quantum number once the electric field is applied.

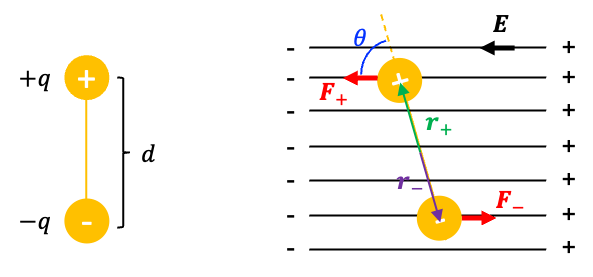

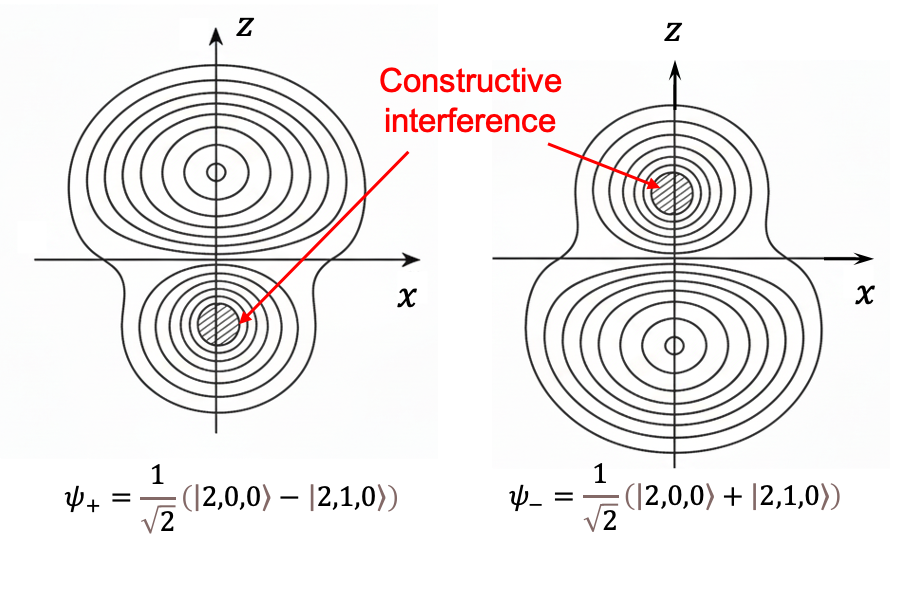

The fact that the level exhibits a first-order Stark effect for

and

implies that their electron distributions are no longer spherically symmetric and acquire a permanent electric dipole moment along the field direction (see diagram below). Furthermore, the three distinct energy levels,

,

and

, classically suggest that the dipole moment has magnitude

and three possible orientations: parallel, antiparallel and perpendicular to the field.

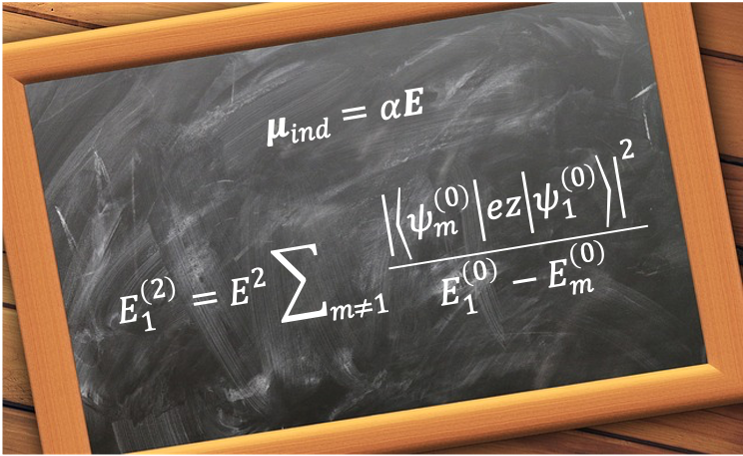

Because the Stark energy shifts in hydrogenic atoms are proportional to the first power of the electric field, the phenomenon is known as the linear Stark effect. Although the ground state of hydrogen does not exhibit a linear Stark effect, it does exhibit a quadratic Stark effect, which we will explore in the next article.