A semiconductor is a crystalline material whose atomic bonding produces a band gap small enough to allow controllable charge-carrier generation and conductivity between that of a conductor and an insulator.

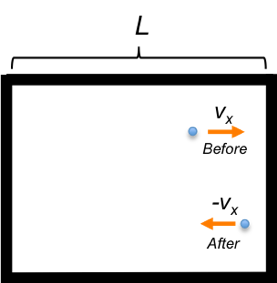

Silicon (Si) and gallium arsenide (GaAs) are common base materials in the manufacture of semiconductors. Si has a diamond cubic crystal structure, where each Si atom, which has four valence electrons, is covalently bonded to four neighbouring Si atoms, forming a tetrahedral arrangement. When boron (B), a trivalent element, is added, it replaces a Si atom in the lattice. Since B has only three valence electrons, it forms three covalent bonds with neighbouring Si atoms, leaving one bond unfulfilled. This unfulfilled bond, which lacks an electron, is known as a “hole”. With sufficient energy, such as in the presence of an electric field, an electron from a neighboring Si atom can move into the hole, forming a covalent bond with the B atom (the acceptor atom) and leaving a new hole in its original position. The ionised B atom becomes negatively charged, while the ionised Si atom is positively charged. As this process repeats, the hole (or the positively charged atom) appears to move through the lattice in the opposite direction to the movement of the electrons. This type of doped material is called a p-type semiconductor (see diagram below).

![]()

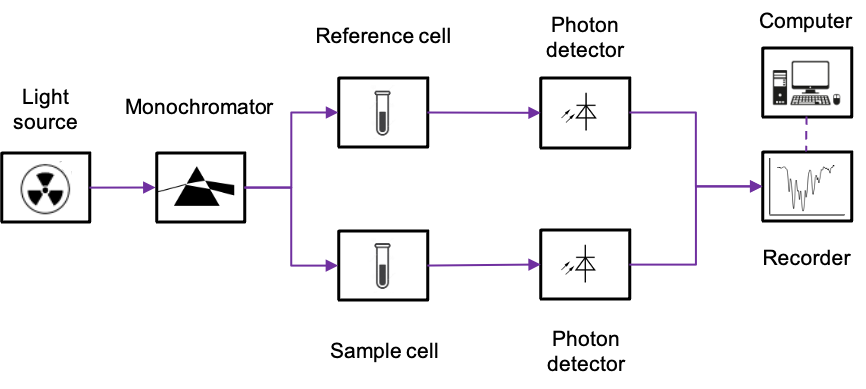

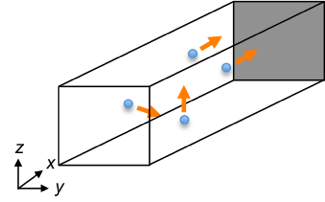

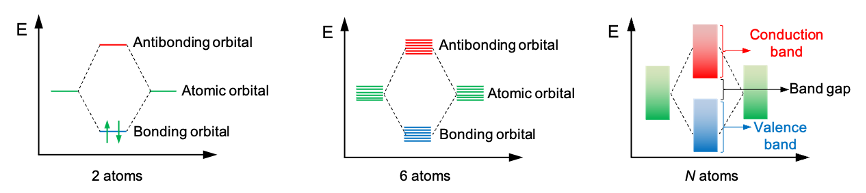

The above phenomenon can also be understood through molecular orbital (MO) theory. When two atoms overlap, two MOs are formed: a bonding orbital and an antibonding orbital. For three atoms, three MOs are produced — bonding, non-bonding and antibonding — while the orbital overlap of four atoms results in four MOs: two bonding and two antibonding orbitals. In general, a chain of atoms generates

molecular orbitals. If

is large, the energy levels of these

MOs merge to form an energy band (see diagram below).

At the ground state of solid Si, the highest energy band that is filled with electrons is known as the valence band. The next higher energy band, the conduction band, can be filled if sufficient energy excites electrons in the valence band to move into it. The energy difference between the valence band and the conduction band is called the band gap, the magnitude of which depends on the type of base material used.

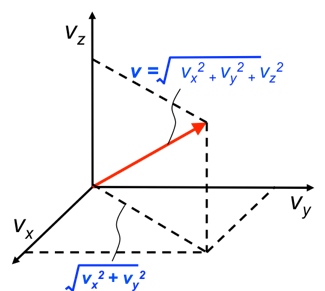

Conversely, when phosphorus (P), a pentavalent element, is introduced, it forms four covalent bonds with neighbouring silicon atoms using four of its valence electrons. The fifth electron, however, is not involved in bonding and remains loosely bound to the P atom. This electron can be easily excited to the conduction band with a small amount of thermal energy, allowing it to move freely through the lattice and leaving the ionised donor P atom positively charged. As a result, the addition of P creates an n-type semiconductor (see diagram below), where free electrons contribute to electrical conductivity.

![]()

Another base semiconductor material is gallium arsenide (GaAs), where each gallium (Ga) atom is tetrahedrally coordinated to four arsenic (As) atoms, and vice versa, resulting in no free electrons available to conduct electricity. If an impurity like beryllium is added to GaAs, it replaces a Ga atom and introduces holes (p-type) into the material because Be has only two valence electrons. On the other hand, when Si is used as a dopant, it substitutes for Ga, resulting in an n-type semiconductor.

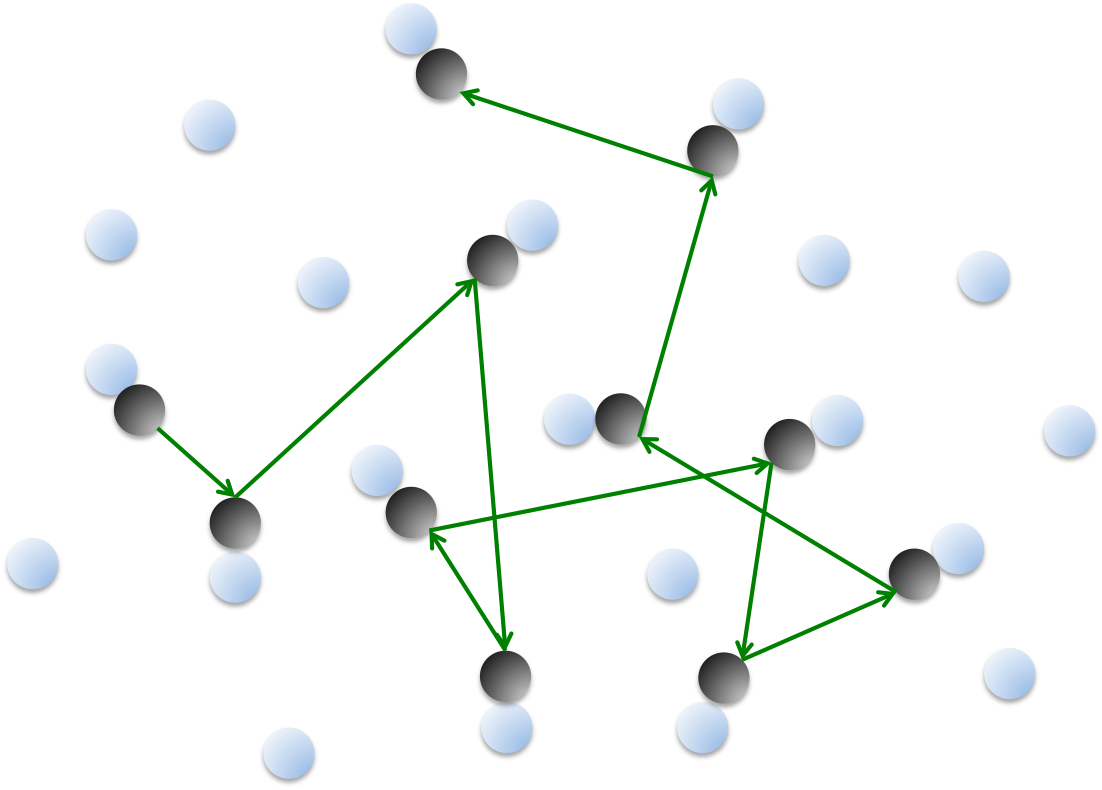

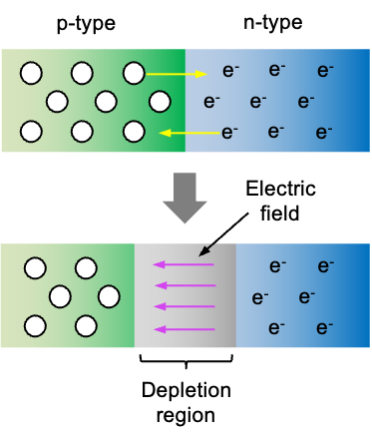

The magic happens when a p-type semiconductor is connected to an n-type semiconductor, creating a p-n junction (see diagram below). Free electrons (negative charge carriers) from the n-type side begin to diffuse into the p-type side, where they recombine with holes. This recombination reduces the number of free carriers on the p-type side near the junction, leaving behind positively charged donor ions on the n-type side. Similarly, holes (positive charge carriers) from the p-type side diffuse into the n-type side and recombine with free electrons, leaving behind negatively charged acceptor ions in the p-type side. This process establishes an electric field across the junction that opposes further diffusion of carriers. Eventually, a state of equilibrium is reached where the diffusion of electrons and holes is balanced by the electric field, generating a depletion region — an electrically neutral region devoid of any mobile charge carriers. This equilibrium can be easily disrupted when electrons from the n-type side gain additional energy from an external source.

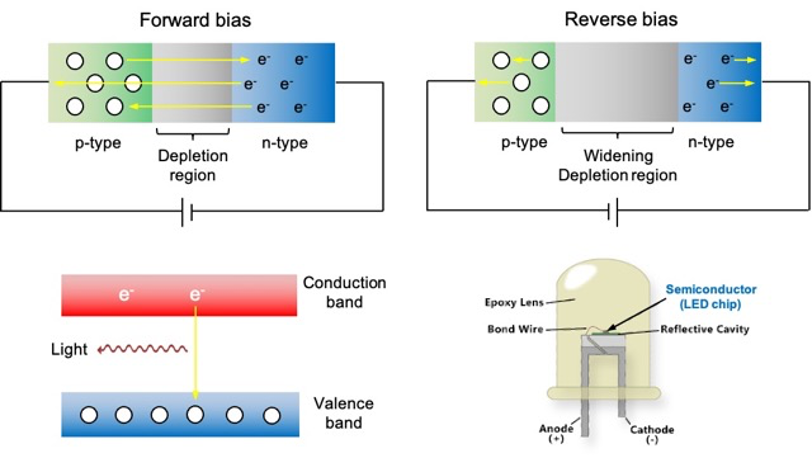

When a voltage is applied across the p-n junction, with the positive terminal connected to the p-type material and the negative terminal connected to the n-type material, forward bias occurs (see diagram below). In this state, electrons from the n-type material gain energy and cross the junction into the p-type material. The majority recombine with holes, while a small fraction continues to drift through the p-type material and into the external circuit, contributing to the current flowing through the device.

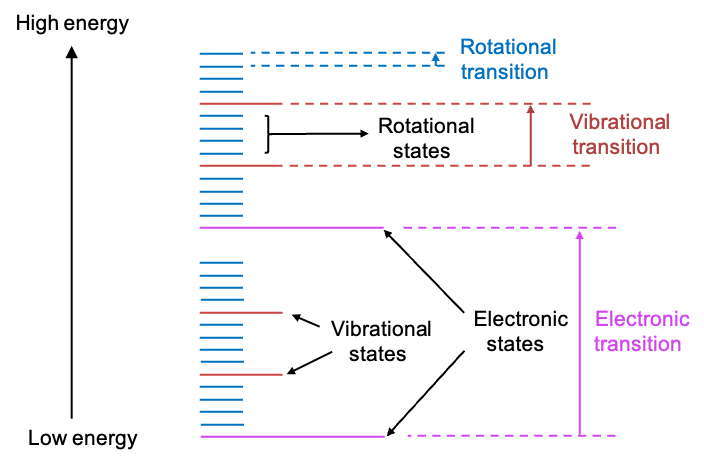

In the MO model, electrons flowing in the circuit are in the conduction band. Some of them relax to a more stable state in the valence band during recombination of a free electron with a hole. When this occurs, a photon with energy corresponding to the semiconductor’s band gap energy is emitted. Such a circuit design is known as a light-emitting diode (LED), with the colour of the emitted light determined by the band gap energy. For instance:

-

- Infrared LEDs (e.g. GaAs) emit light at longer wavelengths, around 850 nm.

- Red LEDs (e.g. GaAlAs) emit at approximately 630 nm.

- Green LEDs (e.g. InGaN) emit around 525 nm.

- Blue LEDs (e.g. InGaN) emit at about 470 nm.

But why is it called a diode?

If a reverse voltage is applied, it increases the electric field across the p-n junction. This results in more electrons being pulled away from the junction in the n-type region and more holes being pulled away from the junction in the p-type region, leading to the widening of the depletion region. This ultimately prevents the movement of the charge carriers when a steady-state is attained, a condition we refer to as reverse bias.

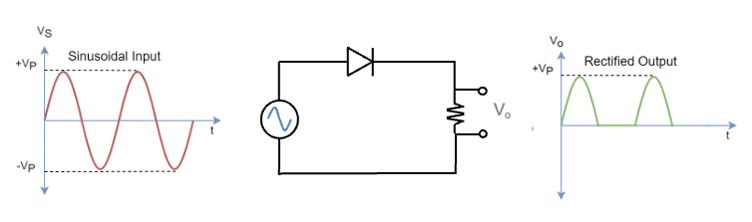

Consequently, a p-n junction functions as a diode, which is a device that allows current to flow in one direction while blocking it in the reverse direction (see diagram below). A regular diode, one that does not emit light when current passing through it, has moderately doped p and n regions, while an LED generally has heavily doped p and n regions. This higher doping concentration increases the probability of electron-hole recombination, which is essential for light emission.

By adjusting the intensities of red, green and blue (RGB) LEDs, the three different coloured LEDs can be combined to create a wide range of white light shades. These “white” LEDs are widely used in home lighting, automotive lighting and electronic displays.

Previous article: Covalent and molecular solids

Content page of solids

Content page of intermediate chemistry

Main content page