A differential rate law mathematically describes the rate of a reaction in terms of the change in the concentration of a reactant over time.

Eq6 of the previous article is an example of a differential rate law, which can be further analysed by considering the decomposition of dinitrogen pentoxide in a rigid vessel:

\rightleftharpoons&space;2NO_2(g)+\frac{1}{2}O_2(g)\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;7)

We monitor the progress of the reaction by measuring the amount of NO2 liberated via spectroscopic methods, with eq1 becoming:

Since the magnitude of the overall rate of a reaction is the same regardless of which chemical species is monitored, if we were also able to measure the amount of O2 produced or the amount of N2O5 consumed, we would, in principle, obtained:

However, for every two moles of NO2 produced over a certain time, t, half a mole of O2 is liberated and 1 mole of N2O5 is consumed. This is inconsistent with eq8, as  . Therefore, eq8 has to be modified as follows:

. Therefore, eq8 has to be modified as follows:

Since the volume of the vessel V is constant, we can divide the modified equation throughout by V and express the rate of reaction in terms of the rate of change in concentrations of the species:

![\frac{1}{4}\frac{d[NO_2]}{dt}=\frac{d[O_2]}{dt}=-\frac{1}{2}\frac{d[N_2O_5]}{dt}\; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; 9](https://latex.codecogs.com/gif.latex?\frac{1}{4}\frac{d[NO_2]}{dt}=\frac{d[O_2]}{dt}=-\frac{1}{2}\frac{d[N_2O_5]}{dt}\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;9)

Eq9 shows that even though the rate of consumption of a species in a reaction may be different from the rate of formation of another species in the same reaction, the magnitude of the overall rate of the reaction must be the same, regardless of the species we are measuring. If we rewrite eq7 as: \rightleftharpoons&space;4NO_2(g)+O_2(g)) and compare it with eq9, we see that:

and compare it with eq9, we see that:

-

- the rate of change of a species in a reaction is always multiplied by the reciprocal of its stoichiometric coefficient; and

- the rate of change of a reactant is always negative.

Hence, we can write the differential rate equation for the decomposition of N2O5 as:

![\frac{1}{4}\frac{d[NO_2]}{dt}=k[N_2O_5]\; \; or\; \;\frac{d[O_2]}{dt}=k[N_2O_5]\; \; or\; \;-\frac{1}{2}\frac{d[N_2O_5]}{dt}=k[N_2O_5]](https://latex.codecogs.com/gif.latex?\frac{1}{4}\frac{d[NO_2]}{dt}=k[N_2O_5]\;&space;\;&space;or\;&space;\;\frac{d[O_2]}{dt}=k[N_2O_5]\;&space;\;&space;or\;&space;\;-\frac{1}{2}\frac{d[N_2O_5]}{dt}=k[N_2O_5])

In general, for a reaction

![rate=\frac{1}{p}\frac{d[P]}{dt}=\frac{1}{q}\frac{d[Q]}{dt}=...=-\frac{1}{a}\frac{d[A]}{dt}=-\frac{1}{b}\frac{d[B]}{dt}=...\; \; \; \; \; \; \; \; 10](https://latex.codecogs.com/gif.latex?rate=\frac{1}{p}\frac{d[P]}{dt}=\frac{1}{q}\frac{d[Q]}{dt}=...=-\frac{1}{a}\frac{d[A]}{dt}=-\frac{1}{b}\frac{d[B]}{dt}=...\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;\;&space;10)

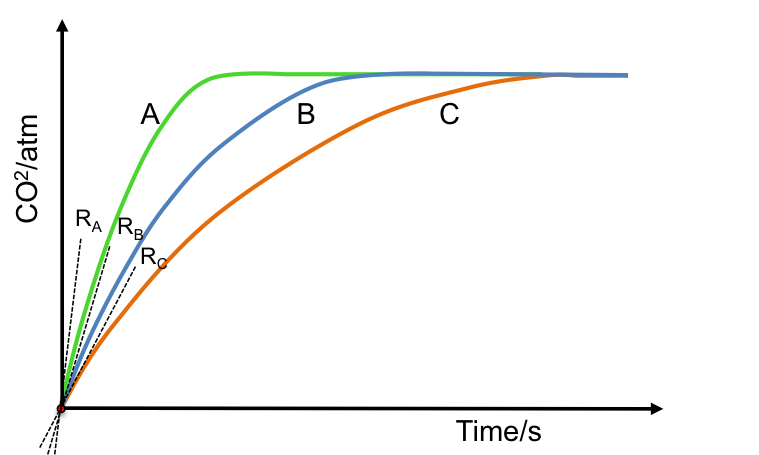

Comparing the rate equations for the reaction between CaCO3 and HCl (eq6) and that for the decomposition of N2O5, we see that the rates of reaction are directly proportional to the concentration of the respective reactants. This, however, is not always the case. For certain reactions, the rate can be proportional to the square of the reactant or even proportional to the product of the concentrations of two or more reactants. Here are some examples of rate laws:

|

Stoichiometric equation

|

Rate law

|

| CH3COOC2H5 + OH– → CH3COO– + C2H5OH |

rate = k[CH3COOC2H5][OH–] |

| CH3CHO → CH4 + CO |

rate = k[CH3CHO]3/2 |

| 2N2O5 → 4NO2 + O2 |

rate = k[N2O5] |

| NO2 + CO → NO2 + CO2 |

rate = k[NO2]2 |

In short, a rate law cannot be predicted from the reaction’s stoichiometric equation. It has to be determined experimentally.

Question

The differential rate equation of eq7 can be expressed as ![\frac{d[N_2O_5]}{dt}=-k[N_2O_5]](https://latex.codecogs.com/gif.latex?\frac{d[N_2O_5]}{dt}=-k[N_2O_5]) . If eq7 is written as

. If eq7 is written as  , the rate equation will be

, the rate equation will be ![\frac{d[N_2O_5]}{dt}=-2k[N_2O_5]](https://latex.codecogs.com/gif.latex?\frac{d[N_2O_5]}{dt}=-2k[N_2O_5]) . How do we reconcile the difference?

. How do we reconcile the difference?

Answer

For the first rate equation, ![\frac{d[N_2O_5]}{dt}=-k_1[N_2O_5]](https://latex.codecogs.com/gif.latex?\frac{d[N_2O_5]}{dt}=-k_1[N_2O_5])

where k1 is the rate constant with reference to the reaction  .

.

For the second rate equation, ![\frac{d[N_2O_5]}{dt}=-2k_2[N_2O_5]](https://latex.codecogs.com/gif.latex?\frac{d[N_2O_5]}{dt}=-2k_2[N_2O_5])

where k2 is the rate constant with reference to the reaction  .

.

Comparing the two rate equations, k1 = 2k2.

A reaction can be written in many ways by multiplying or dividing the stoichiometric coefficients on both sides of the reaction by different factors. This implies that many rate equations can be written for a particular reaction. We just need to specify which stoichiometric form of the reaction we are referring to for the rate equation presented.