A permutation of a set is an ordered arrangement of its elements.

Distinct elements

Consider the task of filling  buckets, each with a ball chosen from a pool of

buckets, each with a ball chosen from a pool of  distinct numbered balls. There are

distinct numbered balls. There are  possible choices for the first bucket. Once the first ball is used, only

possible choices for the first bucket. Once the first ball is used, only  choices remain for the second bucket, then

choices remain for the second bucket, then  choices for the third bucket, and so on. This continues until the last bucket, for which only 1 ball remains.

choices for the third bucket, and so on. This continues until the last bucket, for which only 1 ball remains.

If you have  ways to do a first task, and for each of those,

ways to do a first task, and for each of those,  ways to do a second task, then the total number of ways to perform both tasks is

ways to do a second task, then the total number of ways to perform both tasks is  . This principle extends to any number of sequential tasks. Therefore, the total number of distinct arrangements (permutations) of the

. This principle extends to any number of sequential tasks. Therefore, the total number of distinct arrangements (permutations) of the  balls in

balls in  buckets, denoted by

buckets, denoted by ) or

or  , is the product of the number of choices for each task:

, is the product of the number of choices for each task:

=n(n-1)(n-2)\cdots(2)(1)=n!)

Now, suppose there are  distinct balls but only

distinct balls but only  buckets, where

buckets, where  . Again, there are

. Again, there are  choices for the first bucket,

choices for the first bucket,  for the second, and so on until the

for the second, and so on until the  -th bucket. Since we can also express the number of choices for the second bucket as

-th bucket. Since we can also express the number of choices for the second bucket as  , we have

, we have  ways of filling the

ways of filling the  -th bucket. Hence,

-th bucket. Hence,

=n(n-1)(n-2)\cdots(n-r+1)\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;306)

Multiplying RHS of eq306 by !}{(n-r)!}) gives

gives

=n(n-1)(n-2)\cdots(n-r+1)\frac{(n-r)!}{(n-r)!}=\frac{n!}{(n-r)!}\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;307)

Eq307 gives the general formula for calculating permutations — the number of ways to arrange  objects selected from a set of

objects selected from a set of  distinct objects.

distinct objects.

Question

In a lottery draw for a four-digit winning number, each digit can be any number from zero to nine. How many permutations are possible?

Answer

Total permutations = 10 x 10 x 10 x 10 = 104. In general, the number of permutations for forming a sequence of  positions, where each position can be filled with

positions, where each position can be filled with  possible choices is

possible choices is  .

.

Repeating elements (multinomial permutation)

How many distinct permutations are there of the letters in the word “MISSISSIPPI”? If all letters were distinct, the number of permutations would be 11! = 39,916,800. However, some letters are repeated in the word: 4 I’s, 4 S’s, 2 P’s and 1 M. To understand why we need to adjust for repeated letters, let’s consider the I’s. Suppose we label the four I’s as I1, I2, I3 and I4, treating them as distinct. In any arrangement, these four labelled I’s can be rearranged among themselves in 4! = 24 ways. For example, we could have:

M I1 S S I2 S S I3 P P I4

M I1 S S I2 S S I4 P P I3

M I2 S S I1 S S I3 P P I4

…and so on.

But since these I’s are actually indistinguishable, all 24 of those arrangements represent the same permutation of the word. So, we’ve overcounted each unique arrangement by a factor of 4!. Similarly, the 4 S’s and 2 P’s can be rearranged in 4! ways and 2! ways respectively. Each of these reorderings also causes overcounting, resulting in a total overcounting factor of 4! x 4! x 2!. Therefore, to find the number of distinct permutations of the letters in “MISSISSIPPI”, we divide the total number of arrangements by the total repeated counts:  .

.

In general, if you have a set of  objects, where

objects, where  are identical to each other,

are identical to each other,  are identical to each other but different from the first group, and so on until

are identical to each other but different from the first group, and so on until  , each representing a distinct group of identical items, then the number of distinct permutations is:

, each representing a distinct group of identical items, then the number of distinct permutations is:

where  and

and  is also known as the multinomial coefficient.

is also known as the multinomial coefficient.

Eq308 is used to derive the Boltzmann distribution and Raoult’s law.

A combination is a selection of items where the order does not matter. For example, AB and BA are two different permutations of the set {A,B}, but they represent the same combination. To calculate the number of combinations, we start by counting the permutations (where order does matter), and then correct for overcounting by dividing out the number of ways the selected items can be rearranged.

Suppose we are selecting  objects from a set of

objects from a set of  distinct objects. The number of permutations is given by eq307:

distinct objects. The number of permutations is given by eq307: !}) . However,

. However,  items can be arranged in

items can be arranged in  ways, all of which count as the same combination when order doesn’t matter. There, the number of combinations, denoted by

ways, all of which count as the same combination when order doesn’t matter. There, the number of combinations, denoted by ) or

or  or

or ) , is

, is

=\frac{n!}{r!(n-r)!}\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;309)

Interesting, the number of combinations is also the binomial coefficient.

Question

Show that a mutlinomial permutation can be expressed as a product of combinations.

Answer

Suppose we want to partition a set of  distinct items into

distinct items into  groups of specified sizes

groups of specified sizes  ,

,  , …,

, …,  , where

, where  . The number of ways to select

. The number of ways to select  items for the first group is

items for the first group is

=\frac{n!}{k_1!(n-k_1)!})

The number of ways to select the remaining  items for the second group is

items for the second group is

=\frac{(n-k_1)!}{k_2!(n-k_1-k_2)!})

The number of ways to select the remaining  items for the third group is

items for the third group is

=\frac{(n-k_1-k_2)!}{k_3!(n-k_1-k_2-k_3)!})

and so on until the remaining the number of ways to select the remaining  items for the last group is

items for the last group is

Therefore, the total number of ways to perform all the sequential tasks is

!}\frac{(n-k_1)!}{k_2!(n-k_1-k_2)!}\frac{(n-k_1-k_2)!}{k_3!(n-k_1-k_2-k_3)!}\cdots\frac{k_m!}{k_m!0!})

which simplifies to the RHS of eq308 after all the cancellations.

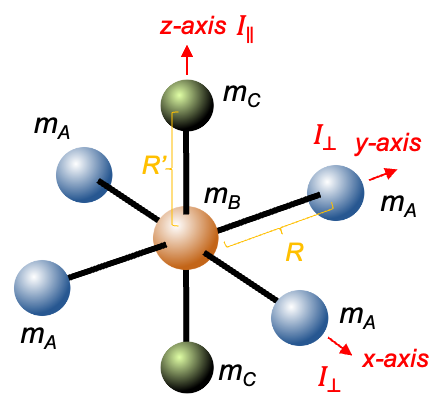

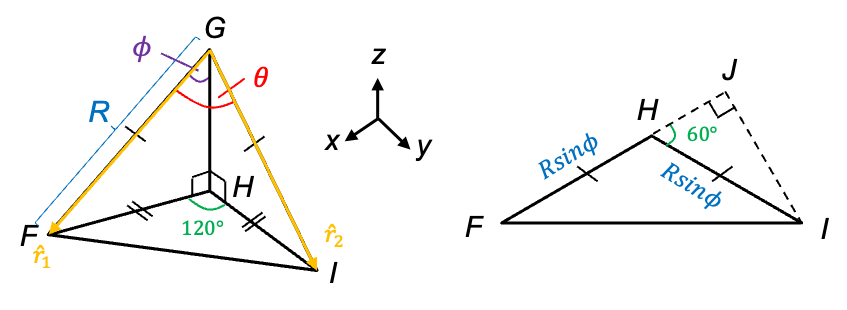

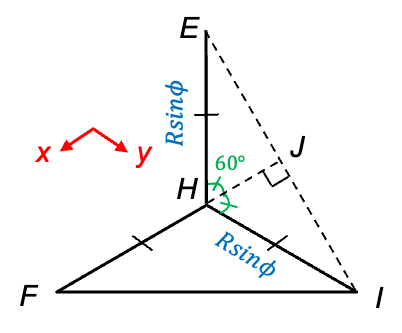

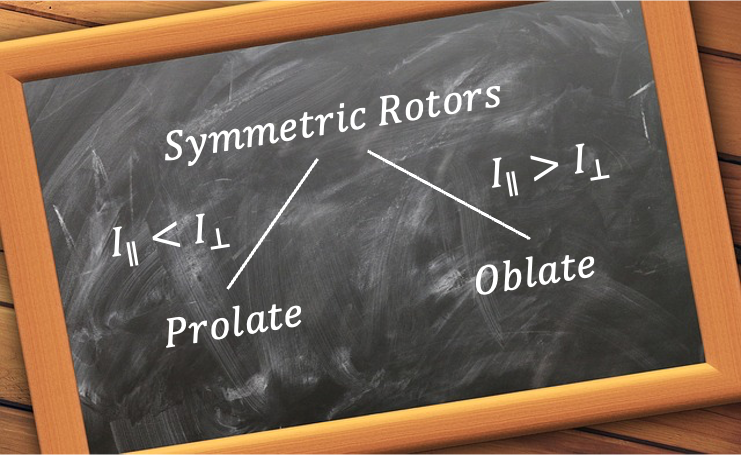

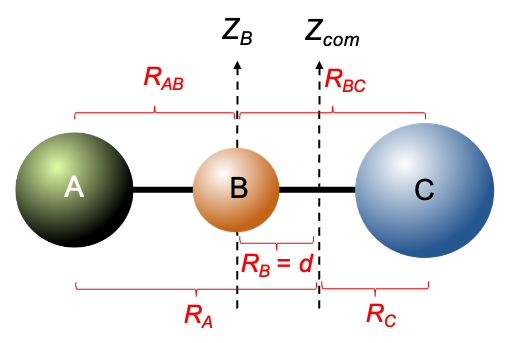

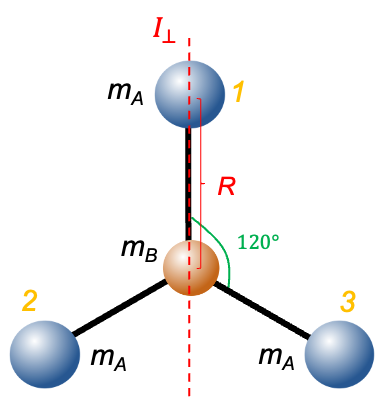

symmetry (e.g. BF3) are characterised by a unique moment of inertia

around the principal axis and two equal moments of inertia

perpendicular to the principal axis, where

. They are derived using simple geometric considerations.

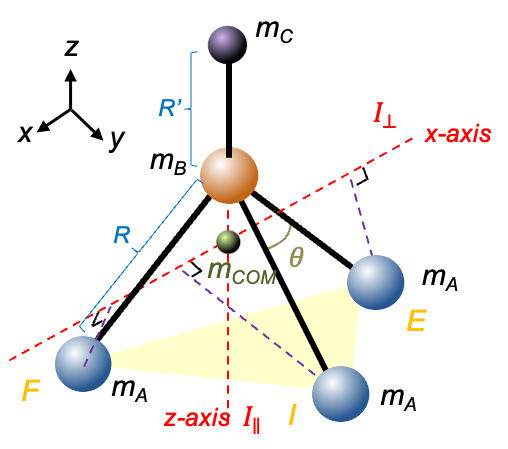

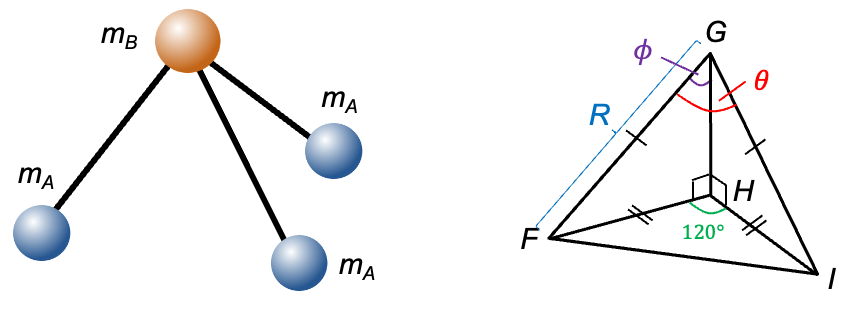

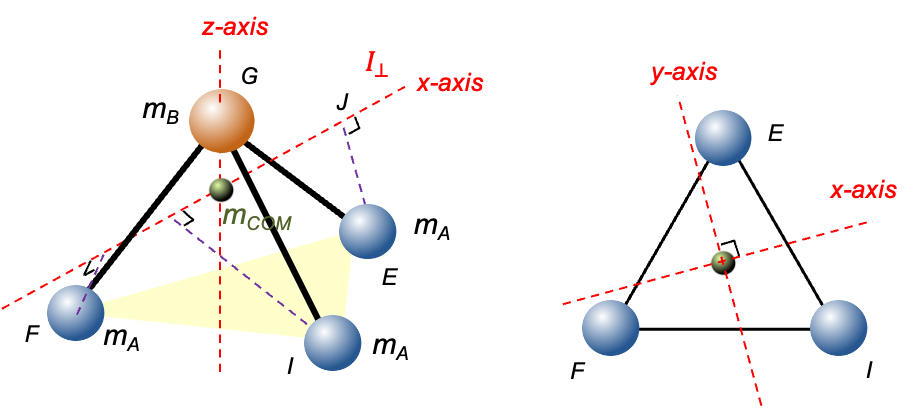

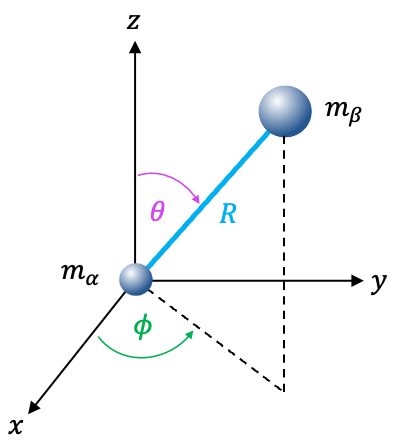

), which is positioned at the origin

. The three A atoms (1,2 and 3), each with mass

, are equally spaced at 120° apart on an imaginary circle of radius

.

-axis, which is perpendicular to the plane of the diagram, is

. Since the three B-A bonds have equal lengths of

, we have

not contribute to

?

. Since atom B lie along the rotational axis, the moment of inertia about this axis is effectively zero due to the absence of perpendicular mass displacement (

).

, we can make use of the coordinates of the atoms that form the base of a trigonal pyramidal molecule mentioned in an earlier article, where

and

:

or

.