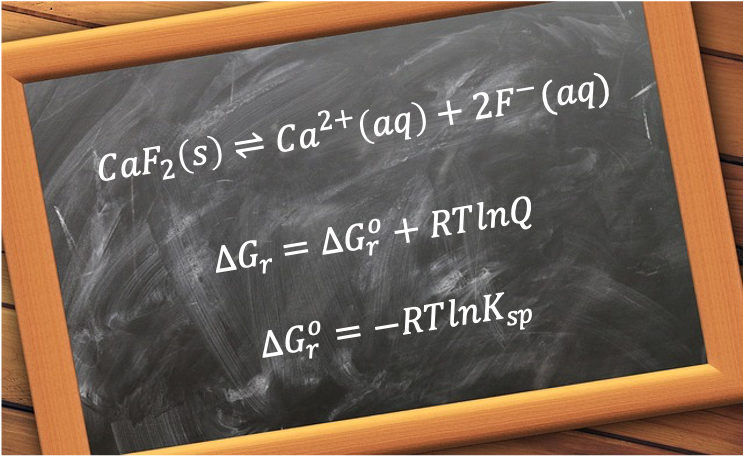

The solubility of calcium fluoride, CaF₂, can be analysed quantitatively using thermodynamic and kinetic principles.

At 25°C, the solubility product of CaF2 is approximately 3.45 x 10-11. The equilibrium expression for the reversible reaction is:

Setting and

, where

is the solubility of CaF₂, yields

Question

If the solubility of CaF2 is 2.10 x 10-4 mol/L, what is its equivalent in parts per million (ppm).

Answer

2.10 x 10-4 mol/L = 2.10 x 10-4 x [40.1 + 2(19.0)] = 1.64 x 10-2 g/L, or equivalently, 16.4 mg/L. Since 1 ppm is approximately equal to 1.00 mg/L in dilute aqueous solutions, the solubility of CaF2 in ppm is 16.4 ppm.

In terms of chemical energetics, CaF2’s standard enthalpy change of lattice energy, determined using the Born Haber cycle, is +2,635 kJmol-1, while its total standard enthalpy change of hydration energy is about -2,624 kJmol-1, resulting in a positive standard enthalpy change of solution of +11.0 kJmol-1. Because the net enthalpy change is slightly endothermic, the process is not enthalpically favoured. However, the thermodynamic feasibility of a reaction is determined by the change in reaction Gibbs energy:

which includes the factor , and where a negative change in reaction Gibbs energy

favours the forward reaction.

To understand why a solution of solid CaF₂ reaches saturation at 2.10 x 10-4 mol/L, we refer to the expression (see this article for derivation):

where

-

is the change in reaction Gibbs energy under non-standard conditions.

is the change in reaction Gibbs energy under standard conditions (pure solids in their standard state, solutes at 1.0 M and T = 298.15 K)

is the reaction quotient (

is the activity of species

and

is the stoichiometric coefficient of species

in the reaction). In dilute solutions, the activity of a species is approximately equal to the concentration of the species. At equilibrium,

.

At the start of dissolution, very little product is formed (), so

and therefore

. Hence, some solid CaF2 must dissolve spontaneously. As the ion concentrations increase and the solubility reaches 2.10 x 10-4 mol/L, the system attains equilibrium, where

. Here,

because a reversible reaction at equilibrium is spontaneous in neither direction. Thus, eq21 becomes:

which at 25°C returns the value kJ/mol.

This positive value indicates that forming Ca²⁺(aq) and F⁻(aq), each at 1.0 mol dm⁻³, from solid CaF₂ under standard conditions is not spontaneous. Nevertheless, dissolution initially occurs to a limited extent until equilibrium is established, consistent with its very small solubility product.

Question

For a reversible reaction, indicates that the forward reaction is spontaneous. Does it mean that the reverse reaction is not occurring simultaneously?

Answer

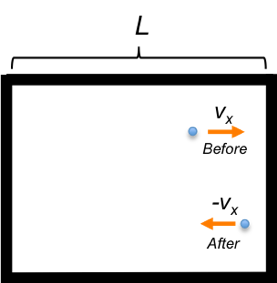

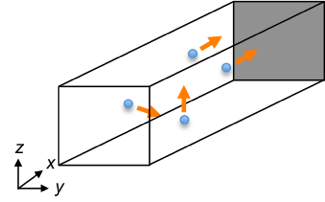

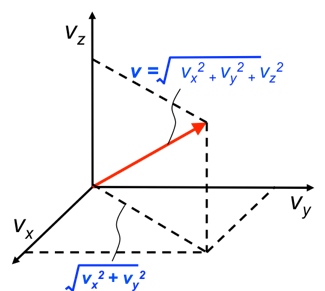

No, the reverse reaction still occurs simultaneously. According to chemical kinetics, there is a statistical tendency for both the forward and reverse reactions to proceed at the same time, with reaction rates given by and

respectively. From eq21, when

, we have

. Substituting eq22 into

gives

, where

because the activity of a pure solid is equal to 1. Therefore,

is equivalent to

. This corresponds to ion concentrations that are momentarily lower than their equilibrium values, favouring the forward reaction (dissolution).

Similarly, when , we have

and hence

. It follows that the ion concentrations are momentarily higher than their equilibrium values, favouring the reverse reaction (precipitation). In all cases, both forward and reverse reactions occur simultaneously; the sign of

determines only the direction of the net change.

Question

Calculate for CaF₂.

Answer

Substituting kJmol-1 and

kJmol-1 into

gives

Jmol-1K-1. The negative value indicates a decrease in entropy under standard conditions. This might seem counterintuitive because a solid dissolving in water is usually associated with a positive change in entropy (greater disorderliness). However, Ca2+ has a +2 charge and F– is a small ion, resulting in a relatively high charge density for both ions. This leads to a more ordered state, in which the ions electrostatically attract shells of polar water molecules around them. Furthermore, standard conditions require a hypothetical concentration of 1.0 M for each ion. At such a high concentration, a massive proportion of the available solvent becomes locked into these ordered hydration shells, decreasing the entropy of the system.

Conversely, in eq20 at the start of the process is positive enough that

, resulting in the spontaneous dissolution of solid CaF2.