What are the factors affecting the capacity of a buffer solution?

The effectiveness (or capacity) of a buffer is dependent on a few factors, namely,

-

- Absolute concentrations of the conjugate acid and conjugate base.

- Relative concentrations of the conjugate acid and conjugate base.

- pKa (for an acidic buffer) of the weak acid in relation to the pH that the buffer is intended to maintain.

- Absolute value of pKa.

- Temperature.

To rationalise the first factor affecting buffer capacity, we refer to the acidic buffer equilibrium:

+H_2O(l)\rightleftharpoons&space;A^-(aq)+H_3O^+(aq))

As mentioned in the previous article, a base OH– added to the buffer reacts with H3O+ to form water. According to Le Chatelier’s principle, the system counteracts this change by shifting the above equilibrium to the right, with some HA further dissociating to replace the H3O+ that has been removed. The higher the concentration of the conjugate acid HA, the greater the amount of HA that can replace the removed H3O+. Similarly, the larger the amount of the conjugate base A–, the greater the buffer’s ability to react with any acid that is added. Hence, buffer capacity is proportional to the combined concentrations of the conjugate acid and conjugate base. Mathematically, the buffer capacity  of a weak conjugate acid/conjugate base pair is given by the following equation (see this article for derivation):

of a weak conjugate acid/conjugate base pair is given by the following equation (see this article for derivation):

![\beta_a=\frac{[HA]_TK_a[H^+]ln10}{\left ( K_a+[H^+] \right )^2}](https://latex.codecogs.com/gif.latex?\beta_a=\frac{[HA]_TK_a[H^+]ln10}{\left&space;(&space;K_a+[H^+]&space;\right&space;)^2})

where [HA]T = [HA] + [A–], i.e. the analytical concentration of HA.

The equation clearly shows that the buffer capacity of an acidic buffer is proportional to the combined concentrations of the conjugate acid and conjugate base.

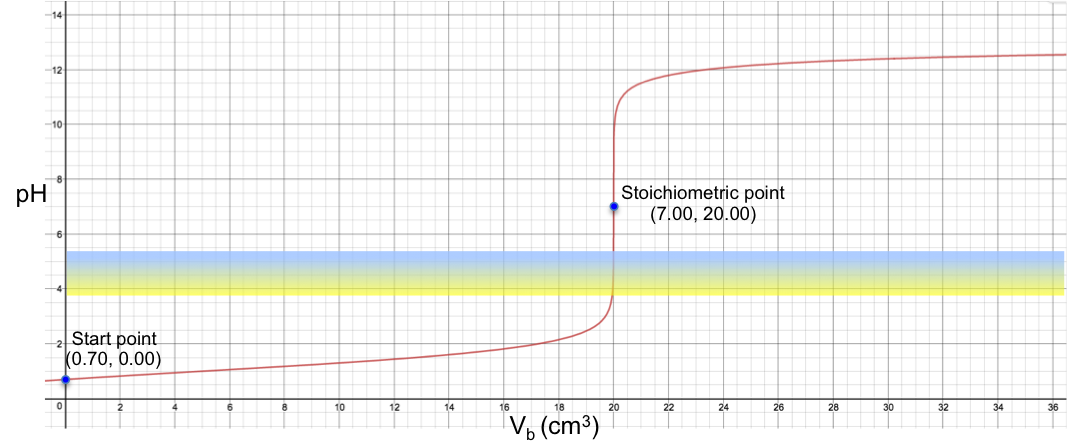

The second factor states that the relative concentrations of the conjugate acid and conjugate base affects buffer capacity. In fact, the maximum buffer capacity of a solution occurs when the concentration of the conjugate acid equals to the concentration of the conjugate base (see this article for details). Substituting ![\frac{[A^-]}{[HA]}=1](https://latex.codecogs.com/gif.latex?\frac{[A^-]}{[HA]}=1) into the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation, we have pH = pKa. In other words, for an acidic buffer to achieve maximum buffer capacity, the pKa of the chosen weak acid must be as close as possible to the pH that the buffer is intended to maintain. This is how the third factor affects buffer capacity.

into the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation, we have pH = pKa. In other words, for an acidic buffer to achieve maximum buffer capacity, the pKa of the chosen weak acid must be as close as possible to the pH that the buffer is intended to maintain. This is how the third factor affects buffer capacity.

It is also important to select an acid with pKa that is neither too high nor too low (fourth factor). An acid with a pKa < 3 (Ka > 10-3) is a relatively strong acid with a high degree of dissociation. Likewise, an acid with a pKa > 11 (Ka < 10-11) is a relatively strong base. As explained in this article, a strong acid (or a strong base) has very low or negligible buffer capacity.

Finally, the buffer capacity of a solution is affected by changes in temperature (fifth factor) since the equilibrium constant is temperature-dependent:

This implies that pKa is also temperature-dependent.

In short, these five factors are important in preparing a buffer solution, which we will discuss in the next article.

Previous article: Overview