The eigenvalues of quantum orbital angular momentum operators are fundamental to understanding the quantisation of angular momentum in quantum mechanics, as they dictate the allowed energy levels and spatial distributions of particles in atomic and molecular systems.

As mentioned in an earlier article, if , a common complete set of eigenfunctions can be selected for the two operators. Let

be the common set of normalised eigenfunctions with eigenvalues

and

for

and

respectively.

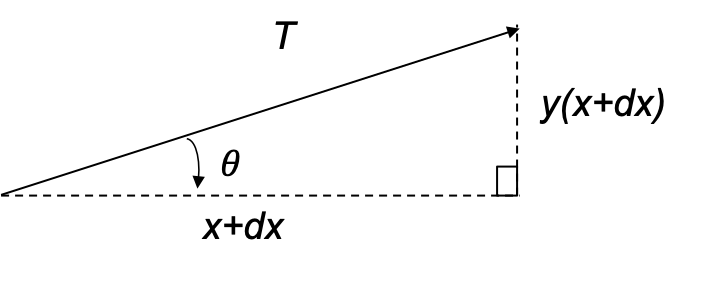

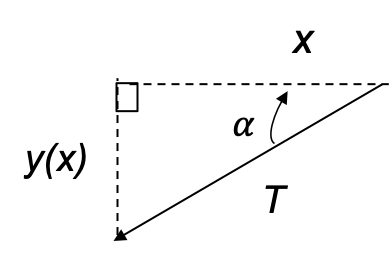

From eq75,

Multiplying the above equation by on the right,

on the left and integrating over all space, we have

Even though is not an eigenfunction of

, we can still find the expectation value of

, which is

Note that we have used the fact that is Hermitian for the 2nd equality (see eq37). Similarly,

. So,

Therefore, has an upper bound and a lower bound. Since the eigenvalues of

has an upper bound and a lower bound, from eq113 and eq114 we have

where ,

,

and

.

If we operate on eq122 with , we supposedly have

However, the above equation contradicts the upper bound eigenvalue of of

. This implies that we must truncate the ladder beyond eq122. Since

, we must have

Using the same argument when operating on eq123 with , we have

If we further operate on eq124 with , we have

Substitute eq116 in the above equation,

Using eq119 where , and eq122,

Since

Similarly, operating on eq125 with and using eq115, eq119 and eq123, we have

Subtracting eq127 from eq126, we have . Since

and

, we have

or

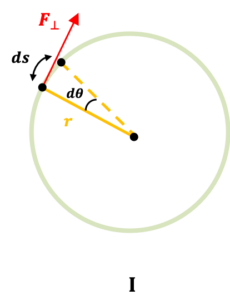

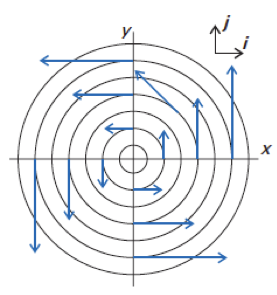

As we know from eq122 and eq123, the value of of a particular system is dependent on the number of consecutive operations on

by

or

, with each operation raising or lowering the eigenvalue of

by

. Therefore,

where

Substituting eq128 in eq129, we have and

. Therefore, the eigenvalues of

are

where .

Substituting in eq127,

where .

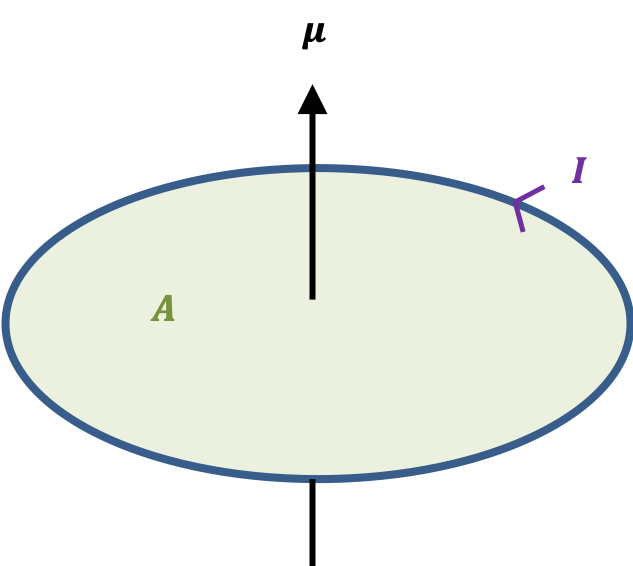

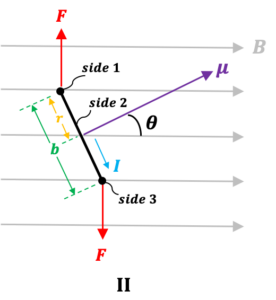

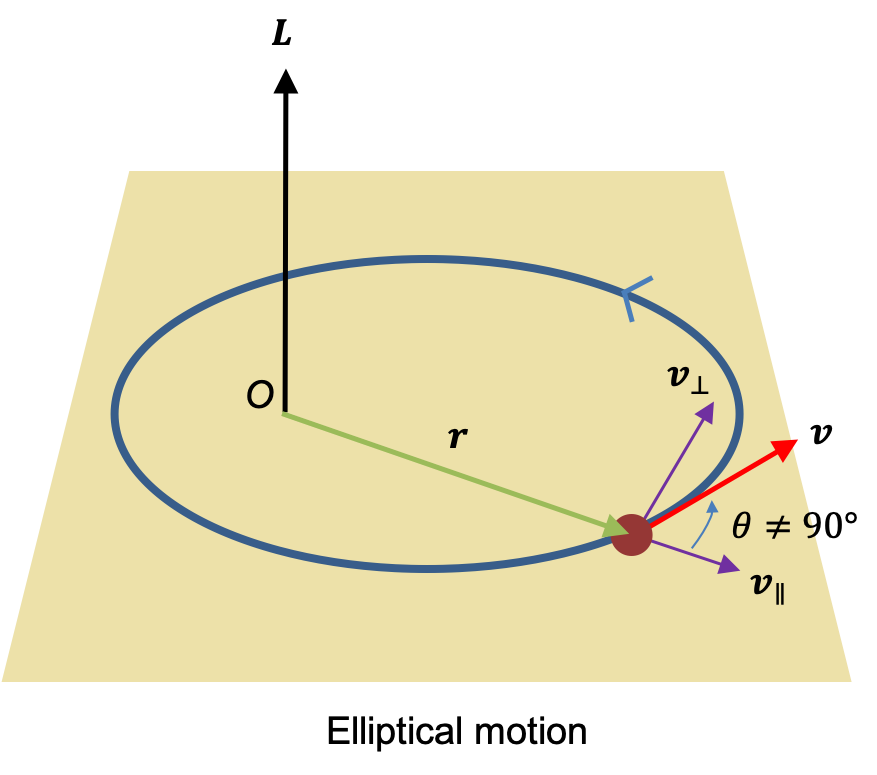

As mentioned in the previous article, the raising and lowering operators also apply to the spin angular momentum and the total angular momentum

. We would therefore expect the eigenvalues of

and

to be

and

respectively, and the eigenvalues of

and

to be

and

respectively. However, the quantum numbers

and

for the orbital angular momentum

, but not the quantum numbers for

and

, are restricted to integers. Therefore,

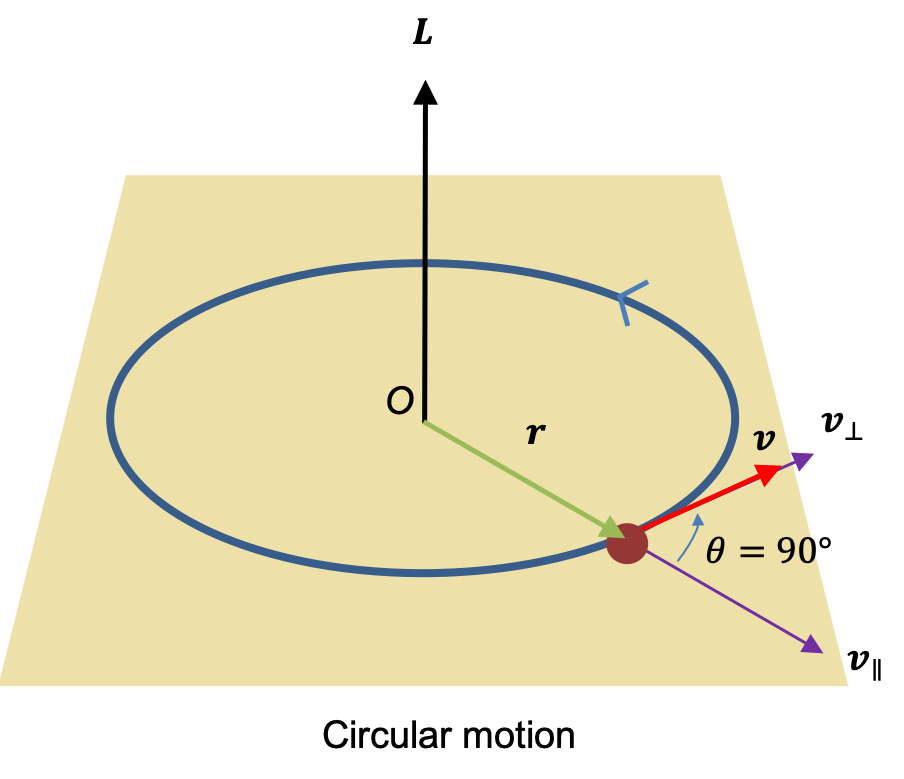

Question

Why are the quantum numbers for restricted to integers?

Answer

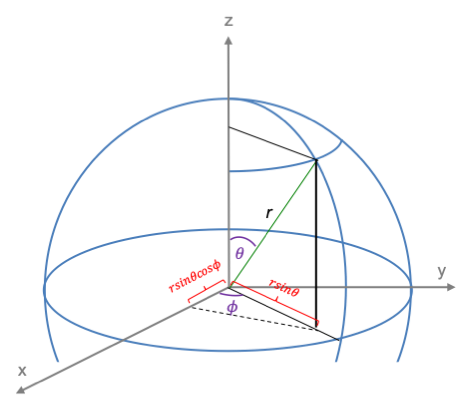

The eigenvalue equation for (see eq95) is:

where .

Since must be single-valued,

The solution to the above equation is . Furthermore,

is also an integer because

. In other words, there are

values of

for a given value of

.

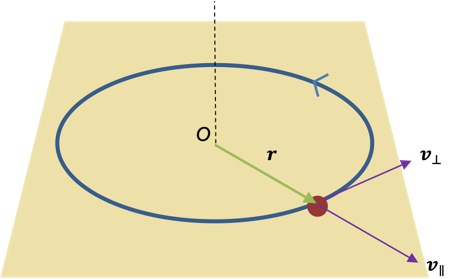

We would arrive at the same results (eq130 and eq131) if we have chosen or

instead of

. The significance of eq130 and eq131 is that we can simultaneously assign eigenvalues of

and

(or

and

or

and

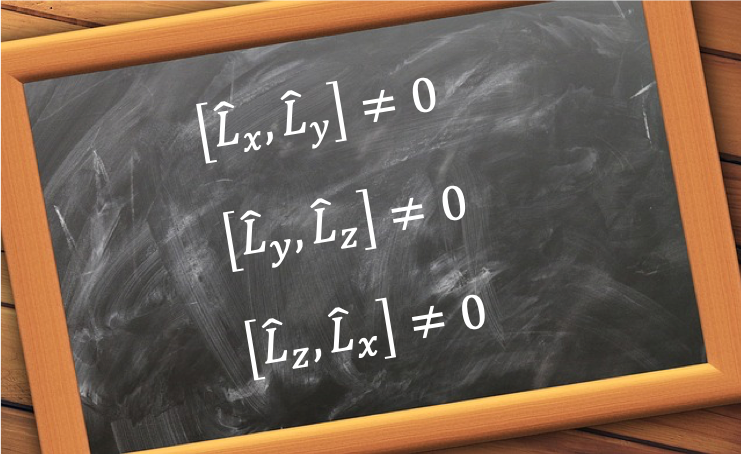

) if the 2 operators commute. This, together with the fact that any pair of component angular momentum operators does not commute, implies that we cannot simultaneously specify eigenvalues of

and more than one component angular momentum operators.

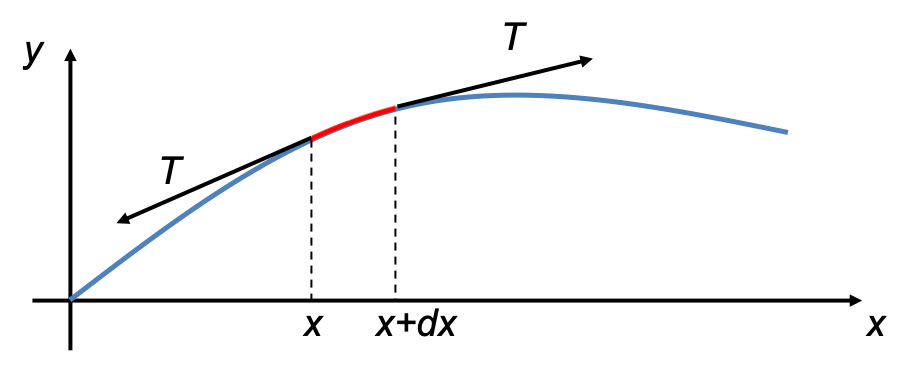

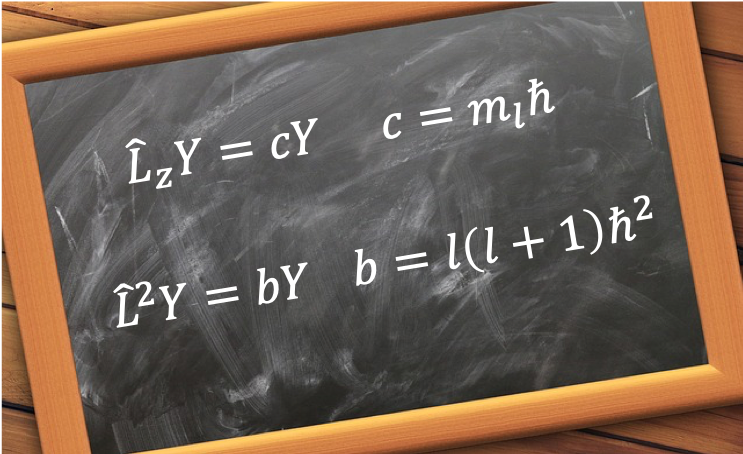

In conclusion, substituting eq130 in eq112 and eq131 in eq117

Since is a function of

and

, we can express the above eigenvalue equations as: