Group theory allows us to determine the symmetries of a molecule, enabling an efficient way to obtain relevant information in infra-red (IR) spectroscopy.

The objective in this article is to use group theory to work out the symmetries of the normal modes of a molecule and then ascertain whether they are IR-active. As an example, let’s consider  , which belongs to the

, which belongs to the  point group. Here’s the corresponding character table:

point group. Here’s the corresponding character table:

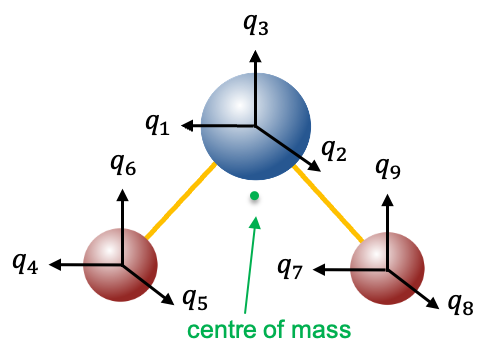

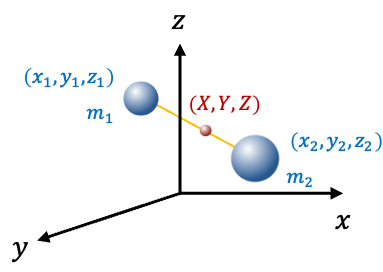

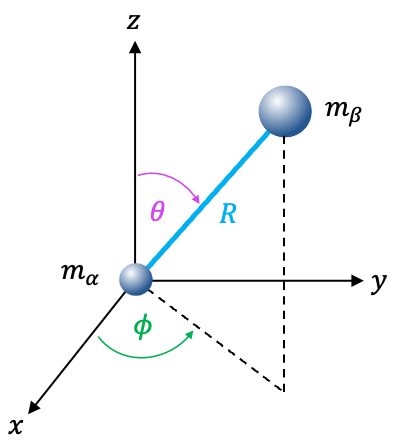

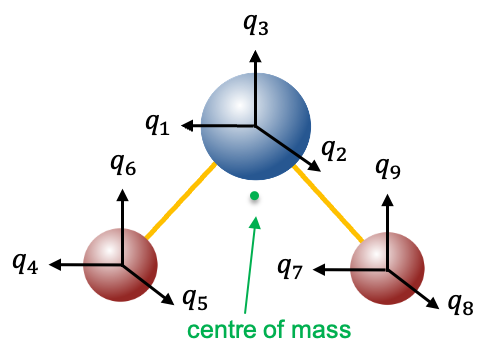

Instead of using Cartesian displacement vectors to form a basis for generating representations of the  point group, as we did in the previous article, we shall use mass-weighted Cartesian coordinate unit vectors

point group, as we did in the previous article, we shall use mass-weighted Cartesian coordinate unit vectors  to form a basis (see diagram above). Since a symmetry operation of

to form a basis (see diagram above). Since a symmetry operation of  transforms

transforms  into an indistinguishable copy of itself, it transforms each of the elements of the basis set into a linear combination of elements of the set (see eq55 to eq61). Therefore,

into an indistinguishable copy of itself, it transforms each of the elements of the basis set into a linear combination of elements of the set (see eq55 to eq61). Therefore,  centred on every atom of

centred on every atom of  generate a representation

generate a representation  of the

of the  point group. To find the matrices of the representation, we arrange the vectors into a row vector and apply the symmetry operations of the

point group. To find the matrices of the representation, we arrange the vectors into a row vector and apply the symmetry operations of the  point group on it to obtain the transformed vector. The matrices of the representation are then constructed by inspection. For example,

point group on it to obtain the transformed vector. The matrices of the representation are then constructed by inspection. For example,

\xrightarrow{C_2}\(-q_1,-q_2,q_3,-q_7,-q_8,q_9,-q_4,-q_5,q_6\))

The traces of the matrices are

Using eq27a and the character table of the  point group, we have

point group, we have

which implies that the decomposition of the reducible representation is  .

.

Applying the projection operator on each element of the  basis set for all irreducible representations, we have

basis set for all irreducible representations, we have

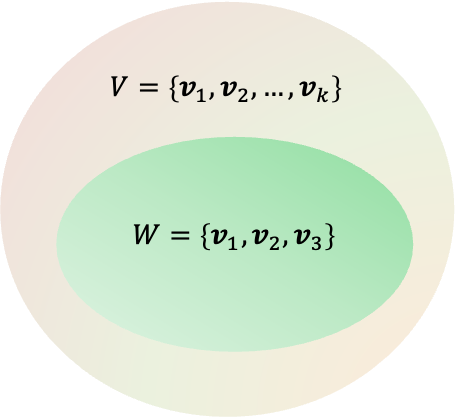

Each equation in the above table is a basis of the irreducible representation it belongs to. Since any linear combination of bases that transform according to a one-dimensional irreducible representation is also a basis of that irreducible representation, we can generate symmetry-adapted linear combinations (SALC) from the above basis vectors that belong to their respective irreducible representations.

We have shown in an earlier article that

-

- the number of orthogonal or orthonormal basis functions of a representation corresponds to the dimension of the representation.

- if

is a basis of a representation

is a basis of a representation  of a group, then any linear combination of

of a group, then any linear combination of  is a basis of a representation

is a basis of a representation  that is equivalent to

that is equivalent to  .

.

This implies that we can always select a set of nine orthonormal SALC for a block diagonal representation that is equivalent to  . Since none of the nine SALCs can be expressed as a linear combination of the others, each SALC, known as normal coordinates

. Since none of the nine SALCs can be expressed as a linear combination of the others, each SALC, known as normal coordinates  , must describe one of nine independent motions of the molecule.

, must describe one of nine independent motions of the molecule.

A quick method to assign the irreducible representations from the decomposition of  to the nine degrees of freedom of

to the nine degrees of freedom of  is to refer to the character table, where the basis functions

is to refer to the character table, where the basis functions  ,

,  and

and  represent the three independent translational motion and

represent the three independent translational motion and  ,

,  and

and  represent the three independent rotational motion. Deducting the irreducible representations associated with these six basis functions from the direct sum of

represent the three independent rotational motion. Deducting the irreducible representations associated with these six basis functions from the direct sum of  , we are left with

, we are left with  ,

,  and

and  . These remaining three irreducible representations correspond to the vibrational degrees of freedom.

. These remaining three irreducible representations correspond to the vibrational degrees of freedom.

To verify whether the three normal modes are IR-active, we refer to the Schrodinger equation for vibration motion (see eq93):

where the separation of variables technique allows us to approximate the total vibrational wavefunction as ) and hence,

and hence,  .

.

Each ) describes a normal mode of the molecule and has the formula (see eq94):

describes a normal mode of the molecule and has the formula (see eq94):

=N_jH_j\biggr\(\sqrt{\frac{\omega_j}{\hbar}}Q_j\biggr\)e^{-\frac{\omega_jQ^2_j}{2\hbar}})

where  is the normalisation constant for the Hermite polynomials

is the normalisation constant for the Hermite polynomials  .

.

The total vibrational energy (see eq96) is

\hbar\omega_j)

A vibrational state of a polyatomic molecule  is characterised by

is characterised by  quantum numbers. Hence, the vibrational ground state of

quantum numbers. Hence, the vibrational ground state of  , where

, where  , is

, is  or

or

e^{-\frac{\omega_jQ_j^2}{2\hbar}}=N\prod_{j=1}^3e^{-\frac{\omega_jQ_j^2}{2\hbar}})

Many IR-spectroscopy experiments are conducted at room temperature, where most molecules are in their vibrational ground state. According to the time-dependent perturbation theory, the transition probability between orthogonal vibrational states within a given electronic state of a molecule is proportional to

where  and

and  are the initial and final states respectively and

are the initial and final states respectively and  is the operator for the molecule’s electric dipole moment.

is the operator for the molecule’s electric dipole moment.

In other words, no transition between states occurs when  . Since the objective is to ascertain the IR activity of each of the three normal modes of

. Since the objective is to ascertain the IR activity of each of the three normal modes of  , it is suffice to study the fundamental transitions, where

, it is suffice to study the fundamental transitions, where  and

and  or

or  or

or  .

.

The next step involves determining which irreducible representation of the  point group

point group  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  belong to. Since the components

belong to. Since the components  ,

,  and

and  represent the electric dipole moment along the

represent the electric dipole moment along the  ,

,  and

and  directions respectively, they transform in the same way as the basis functions

directions respectively, they transform in the same way as the basis functions  ,

,  and

and  respectively (see character table above).

respectively (see character table above).

Question

Show that  , where

, where  represents the symmetry operations of a point group and

represents the symmetry operations of a point group and  .

.

Answer

In general, if =f(x)) , then the function

, then the function ) is invariant under the symmetry operation

is invariant under the symmetry operation  . Every value of

. Every value of  is mapped into

is mapped into  by

by  and we can say that

and we can say that  if

if =f(x)) . The converse is also true, i.e. if the variable

. The converse is also true, i.e. if the variable  of the function

of the function ) transforms according to

transforms according to  , then

, then =f(x)) . From this article, the potential term of the vibrational Hamiltonian for

. From this article, the potential term of the vibrational Hamiltonian for  is

is =U_e+\frac{1}{2}\sum_{j=1}^{3N-6}\lambda_jQ^2_j}) . Since the function

. Since the function ) is invariant under any symmetry operation,

is invariant under any symmetry operation, =U_e+\frac{1}{2}\sum_{j=1}^{3N-6}\lambda_jQ^2_j=U_e+\frac{1}{2}\sum_{j=1}^{3N-6}\lambda_j(R_{\alpha}Q_j)^2}) or simply

or simply

^2=\sum_{j=1}^{3N-6}\lambda_jQ_j^2\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;105)

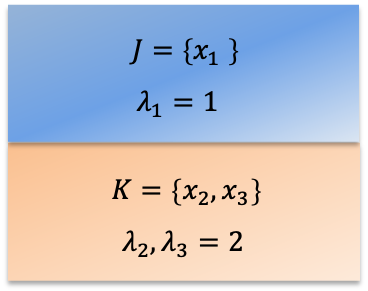

If each  is distinct, then

is distinct, then ^2=Q_j^2) or

or

If  is degenerate, eq55 states that

is degenerate, eq55 states that  and eq105 becomes

and eq105 becomes

^2+\lambda_1(a_{12}Q_1+a_{22}Q_2)^2+\lambda_3(R_{\alpha}Q_3)^2+\cdots=\\\lambda_1Q_1^2+\lambda_1Q^2_2+\lambda_3Q_3^2+\cdots\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;107)

where we have assumed that  and

and  are degenerate.

are degenerate.

As described in this article,  forms a set of orthonormal eigenvectors of the vibrational Hamiltonian. So,

forms a set of orthonormal eigenvectors of the vibrational Hamiltonian. So,  and

and  are orthonormal vectors. The matrix formed by using these vectors as its columns is an orthogonal matrix

are orthonormal vectors. The matrix formed by using these vectors as its columns is an orthogonal matrix  , which is defined as

, which is defined as  . This is because the dot product of different columns will be zero, and the dot product of a column with itself will be 1. Since

. This is because the dot product of different columns will be zero, and the dot product of a column with itself will be 1. Since  if

if  is an orthogonal matrix (see property 11 of this link for proof),

is an orthogonal matrix (see property 11 of this link for proof),  or

or

which implies that  and

and  .

.

The first two terms on LHS of eq107 then becomes  . This implies that

. This implies that ^2) must also be equal to

must also be equal to  in eq105 if

in eq105 if  is degenerate. Therefore,

is degenerate. Therefore,  regardless of whether

regardless of whether  is non-degenerate or degenerate.

is non-degenerate or degenerate.

As mentioned in the above Q&A, if the variable  of the function

of the function ) transforms according to

transforms according to  , then

, then =f(x)) . It follows that if the variable

. It follows that if the variable  of the function

of the function ) transforms according to

transforms according to  , then

, then =f(-x)) , in which case

, in which case  is the reflection operator about the vertical axis of the graph of

is the reflection operator about the vertical axis of the graph of ) against

against  . Therefore, the ground state vibrational wave function

. Therefore, the ground state vibrational wave function  of

of  transforms according to the totally symmetric irreducible representation

transforms according to the totally symmetric irreducible representation  of the

of the  point group because

point group because

=\psi_0(\pm Q_j)=N\prod_{j=1}^3e^{-\frac{\omega_j(\pm Q_j)^2}{2\hbar}}=\psi_0)

Next, let’s analyse the symmetries of  ,

,  and

and  . These three wave functions (see this article) have the same form of:

. These three wave functions (see this article) have the same form of:

Eq108 is a product of two functions  and

and  . Since

. Since  is totally symmetric, the theory of direct product representation states that

is totally symmetric, the theory of direct product representation states that  must transform according to the irreducible representation of the

must transform according to the irreducible representation of the  point group that

point group that  belongs to.

belongs to.

With reference to the  character table above, the theory of direct product representation again finds that the functions

character table above, the theory of direct product representation again finds that the functions  ,

,  and

and  in eq104 transform according to the irreducible representations of

in eq104 transform according to the irreducible representations of  ,

,  and

and  respectively. Therefore, the theory of vanishing integrals states that

respectively. Therefore, the theory of vanishing integrals states that

|

|

|

|

Zero |

Not zero |

|

Zero |

Zero |

|

Not zero |

Zero |

Since  in eq104 for each of the three normal modes, all three normal modes of

in eq104 for each of the three normal modes, all three normal modes of  are IR-active.

are IR-active.

is an even number,

is an odd number, we too end up with eq29. Therefore,

in eq29 represents any number. Taking the derivative of eq29 again,

in eq31 with

gives

, show that eq32 can be used to generate the Hermite polynomials.

in eq32, we have

. Substituting

in eq32, we have

. Repeating the logic, we can generate the rest of the polynomials.

and eq46, show that

.

and integrating over all space,

, where

are the normal modes, into eq32a gives:

is given by eq94.

,