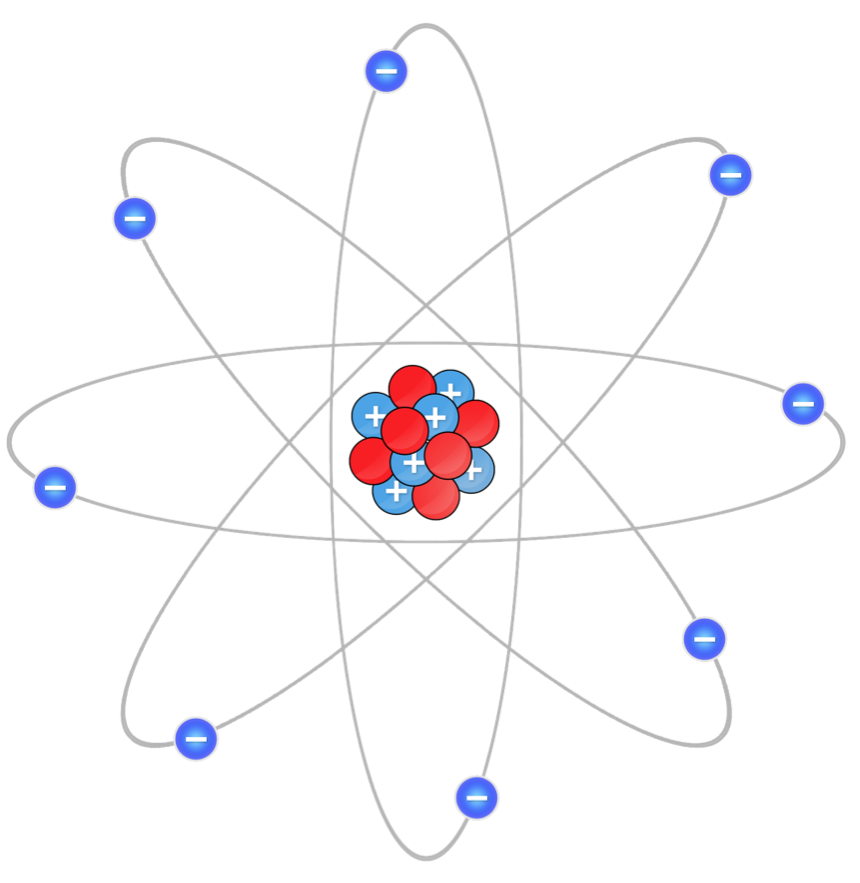

Spin-orbit coupling is the interaction between a particle’s spin angular momentum and orbital angular momentum. An electron orbiting around the nucleus ‘sees’ the nucleus circling it, just as a person on earth perceives the sun circling the earth while the latter orbits around the sun.

This apparent nuclear orbit creates a magnetic field that exerts a torque on the electron’s spin magnetic dipole moment

, resulting in an additional term of

(where

) in the multi-electron Hamiltonian. To derive this term, we consider a 1-electron atom.

Let be the orbital angular momentum of the electron and

be the proton’s current loop, which generates a magnetic field of magnitude

given by the Biot-Savart law. Since

, we have

Substitute eq259 in , we have,

or

, where

and

are unit vectors. Since

and

point in the same direction,

. Multiplying both sides of

by

, we have

, which we substitute in eq65 (where

is the spin analogue of eq61) to give

.

Substituting eq164 and in

yields

For a 1-electron atom, and so

Eq260 can be written in terms of the Larmor frequency of the electron. From eq149, . So,

. Swapping

with the Thomas precession rate

, we obtain the correction term of

.

The total spin-orbit Hamiltonian is

The spin-orbit energy corresponds to the expectation value

, where

is the hydrogenic wavefunction. Since

, we have

. Substituting this and

into

gives:

For a given , we usually express the above equation as:

where is regarded as a constant.

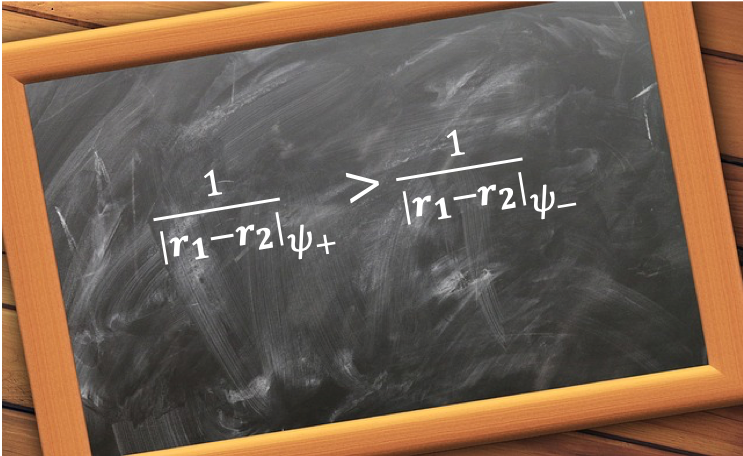

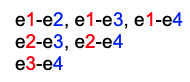

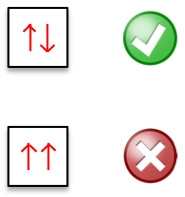

For a multi-electron system,

The spin-orbit energy expression for a multi-electron system is very similar to eq261a if we assume Russell-Saunders coupling, where spin-orbit interactions are weak compared to the Coulomb interaction (). Here, the electrons’ orbital angular momenta couple to form the total orbital angular momentum

separately from their spin angular momenta, which couple to form

. Each electron in the system experiences a force due to its Coulomb interaction with the other electrons

.

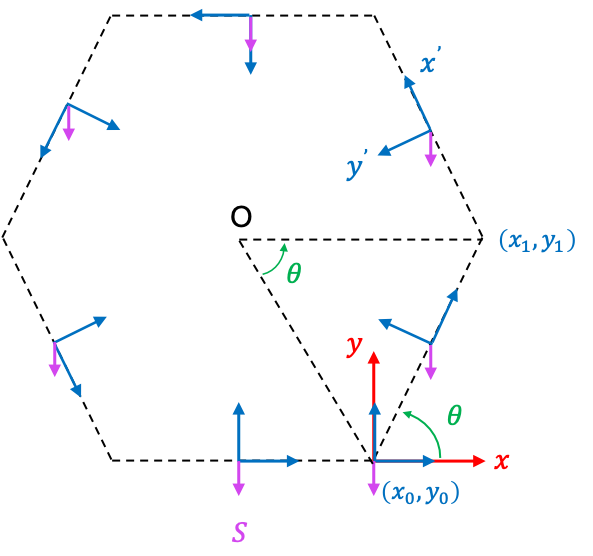

Consider electron at

along the laboratory

-axis and electron

at

on the

-axis. The Coulomb force

between electrons

and

acts in the direction

, pointing downwards and to the right. The component of

perpendicular to the

-axis produces a torque

on electron

, where

. Because the electrons are not symmetrically arranged at every instant, the resultant torque on electron

due to all other electrons is generally non-zero. Since

(see eq71), the individual orbital angular momenta are not conserved. By Newton’s third law, the torque exerted by electron

on electron

is equal and opposite to the torque exerted by

on

. When summed over all electrons, these internal torques cancel, giving

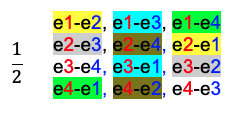

Thus, while the total orbital angular momentum is conserved, the individual

are not. To satisfy

,

and

at all times, the individual orbital angular momenta can change only in direction, leading to their precession about the fixed total orbital angular momentum

. By the same reasoning, the individual spin angular momenta precess around

. Since

, these precessions occur on a much shorter timescale than the subsequent precessions of

and

around the total angular momentum

.

To continue the derivation of the spin-orbit energy expression for a multi-electron system, we decompose the individual orbital and spin angular momenta into components parallel and perpendicular to and

:

Under rapid precession, the time-averaged value of and

vanish. So, the average value of

is

Since and correspondingly

, where

and

are unit vectors,

where .

Substituting eq261c into eq261b gives:

It follows that

If spin-orbit interactions become strong compared to the Coulomb interaction (),

-coupling replaces Russell-Saunders coupling, and the spin-orbit Hamiltonian must be treated in the form of eq261b.