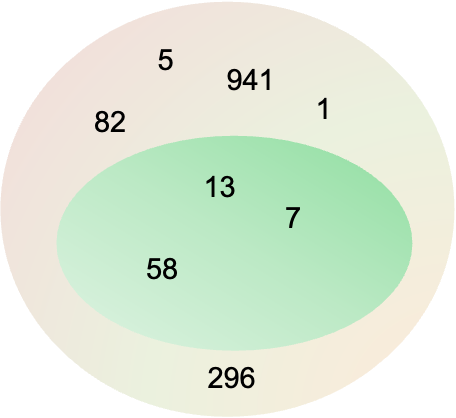

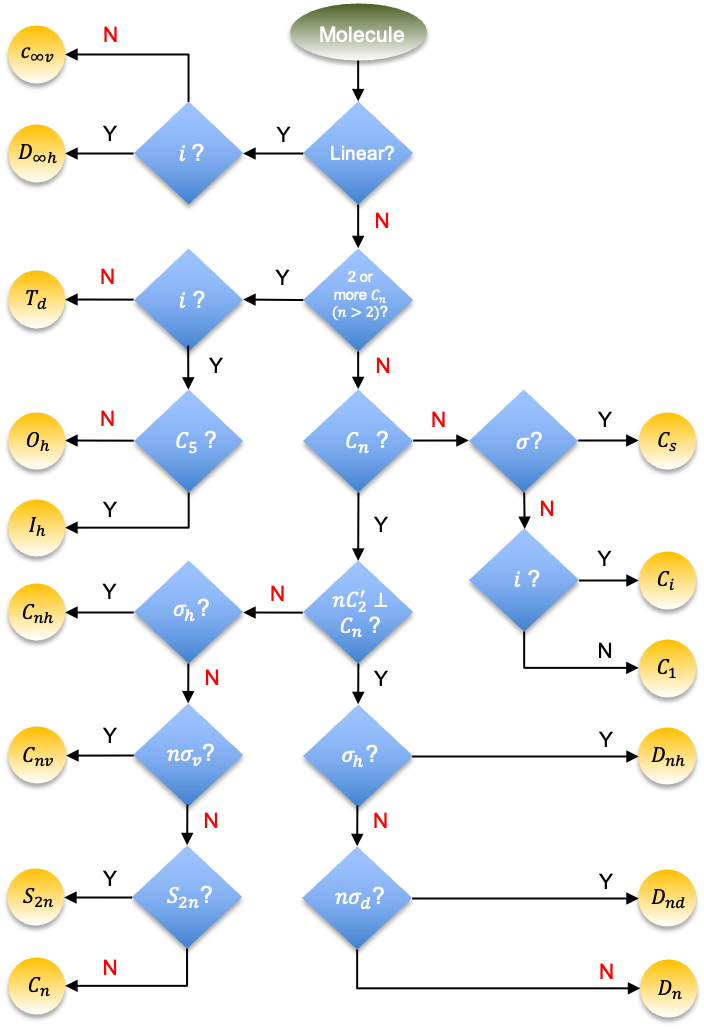

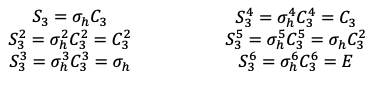

Group theory allows us to determine the symmetries of the degrees of freedom of a molecule in a simple way, especially the vibrational modes of the molecule.

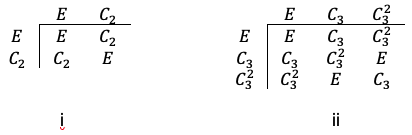

Consider , which belongs to the

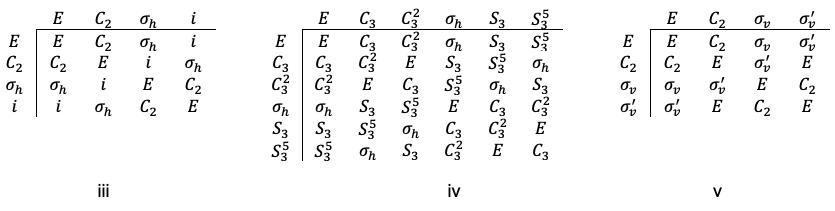

point group with the following character table:

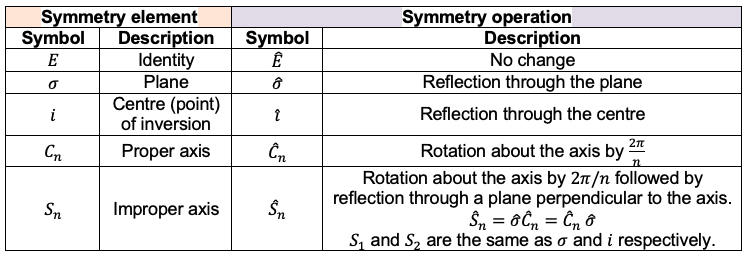

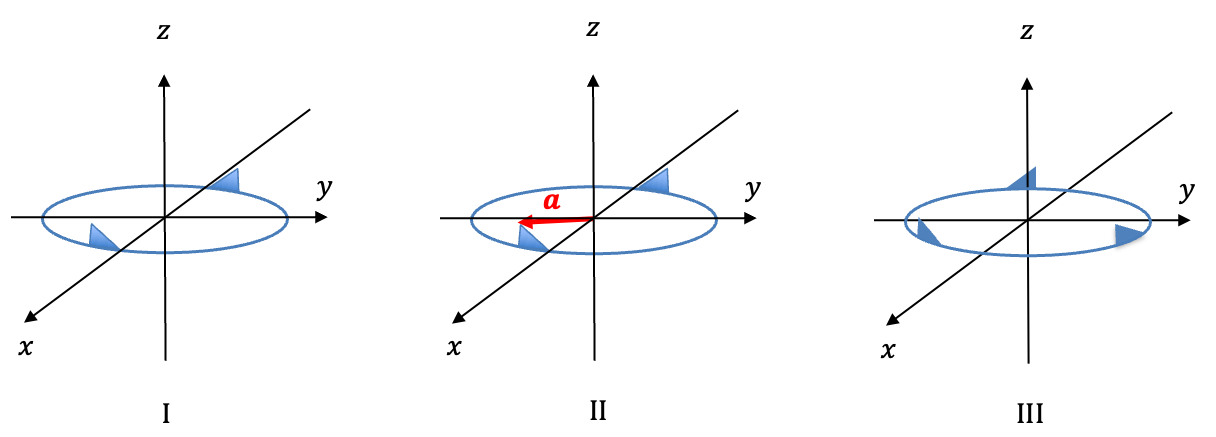

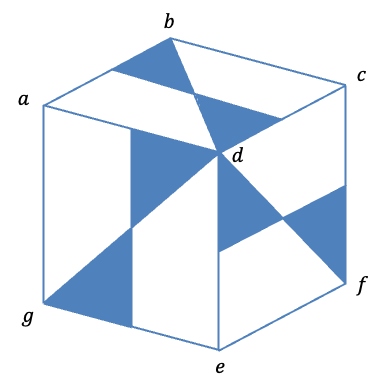

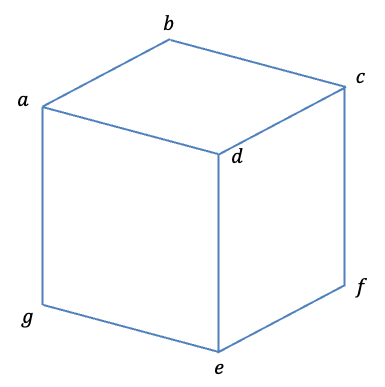

Let’s form a set of basis with 9 unit displacement vectors representing instantaneous motions of the atoms (see diagram above). Since a symmetry operation of transforms

into an indistinguishable copy of itself, it transforms each of the elements of the basis set into a linear combination of elements of the set. Therefore, orthogonal unit vectors centred on every atom of

generate a representation

of the

point group. To find the matrices of the representation, we arrange the unit vectors into a row vector and apply the symmetry operations of the

point group on it to obtain the transformed vector. The matrices of the representation are then constructed by inspection. For example,

The traces of the matrices are

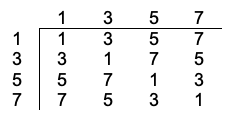

Using eq27a and the character table of the point group, we have

which implies that the decomposition of the reducible representation is .

A quick method to assign the irreducible representations from the decomposition of to the nine degrees of freedom of

is to refer to the character table, where the basis functions

,

and

represent the three independent translational motion, and

,

and

represent the three independent rotational motion. Deducting the irreducible representations associated with these six basis functions from the direct sum of

, we are left with

,

and

. These remaining three irreducible representations correspond to the vibrational degrees of freedom.

To understand how the quick method works, we apply the projection operator on each element of the basis set for all irreducible representations to give

Each equation in the above table is a basis of the irreducible representation it belongs to. Since any linear combination of bases that transform according to a one-dimensional irreducible representation is also a basis of that irreducible representation, we can generate symmetry-adapted linear combinations (SALC) from the above basis vectors that belong to their respective irreducible representations, e.g. belongs to

.

Question

Show that is a basis of

and that it describes the translational motion of

in the

-direction.

Answer

Let be the

-th symmetry operation of the

point group. With reference to the subspace of

, we have

and

because

and

are bases of

.

and

are also bases of

, as

and

.

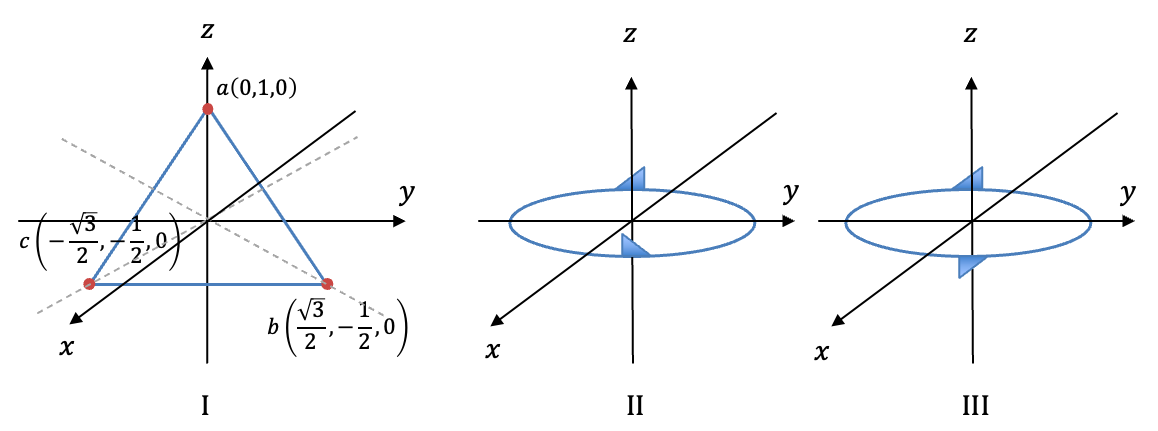

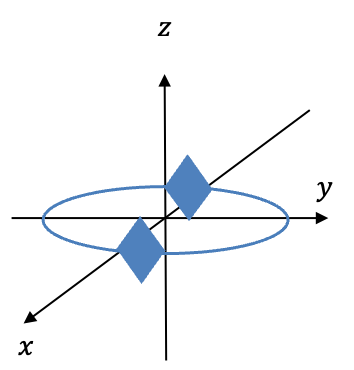

In an earlier article, we explained that the displacement of in the

-direction is described in terms of unit instantaneous displacements vectors that are centred on the atoms, or equivalently, a single instantaneous displacement vector on the centre of mass. Using the second description, we then showed that the translational motion of

in the

-direction transforms according to

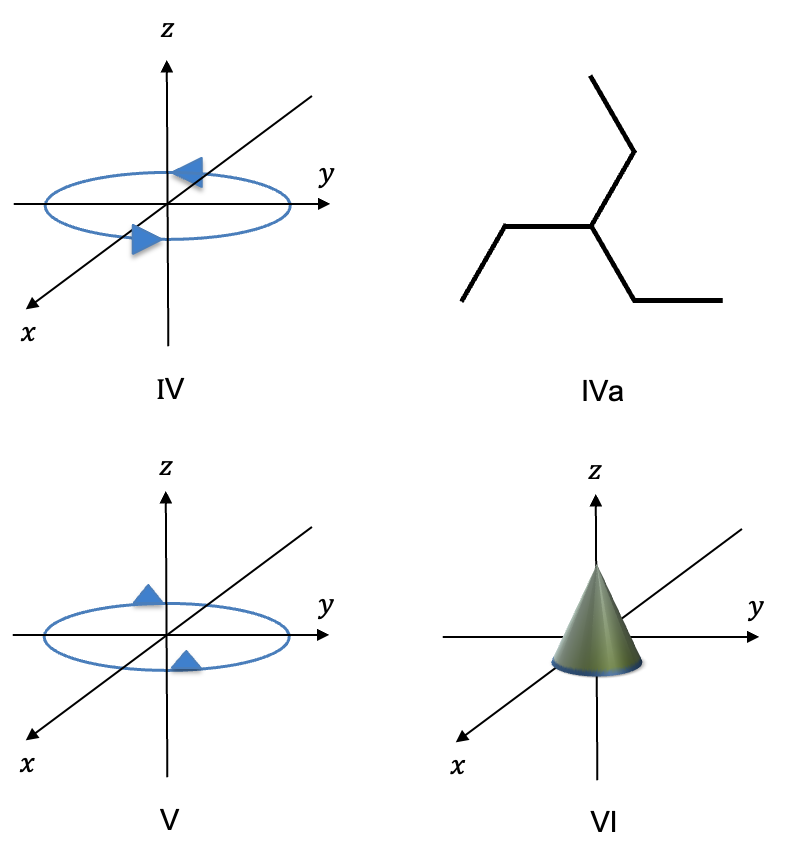

. Since the two descriptions are equivalent (see diagram below), the three

-bases in the first description must transform according to the subspace of

. This is only possible if they are expressed as the SALC

.

Consequently, the SALCs describing the three translational degrees of freedom are:

| SALC | Description | |

| Translation in the |

||

| Translation in the |

||

| Translation in the |

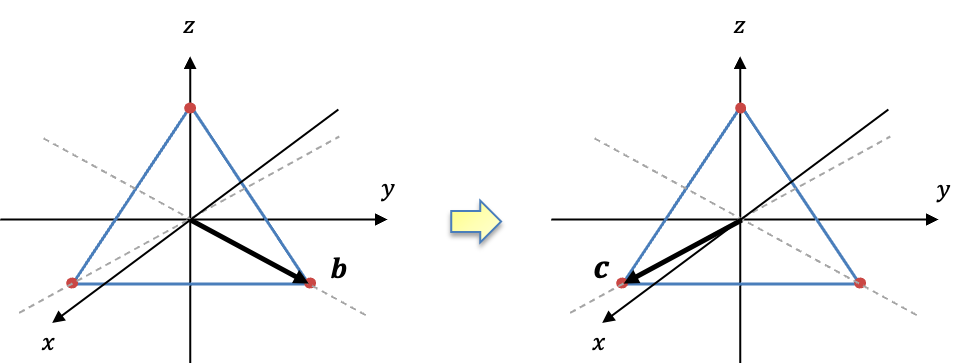

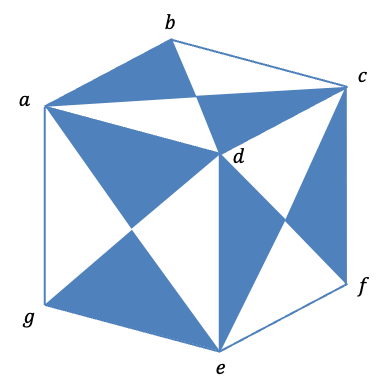

Using the logic mentioned the above Q&A, the rotational motion are given by:

| SALC | Description | |

| Rotation around the centre of mass with reference to the |

||

| Rotation around the centre of mass with reference to the |

||

| Rotation around the centre of mass with reference to the |

where are positive coefficients and each displacement vector is tangent to the relevant circular path (see diagram below).

Why do the remaining three irreducible representations of ,

and

correspond to vibrational degrees of freedom? We have proven, in an earlier article, that if the

basis vectors transform according to a reducible representation

of the

point group, then any linear combination (SALC) of the vectors is also a basis of a reducible representation

that is equivalent to

. We have also shown, in the same article, that the number of linearly independent basis functions of a representation corresponds to the dimension of the representation. Hence, we need to select nine linearly independent SALCs consisting of six SALCs listed in the two tables above and three remaining SALCs, each of which belonging to

,

and

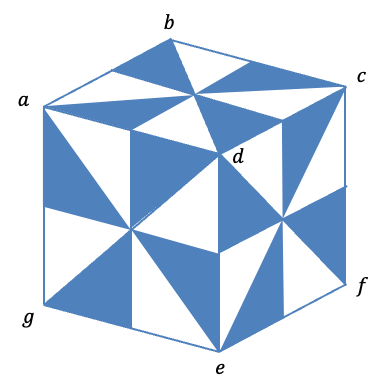

respectively. Since none of the nine SALCs can be expressed as a linear combination of the others, the remaining three SALCs must describe the independent vibrational degrees of freedom of

. The possible vibrational modes, noting that two are totally-symmetric (

) and one is antisymmetric (

) with respect to rotation about the principal axis, are

The SALCs corresponding to these modes have the form:

| SALC | Description | |

| Vibration: symmetric stretching | ||

| Vibration: bending | ||

| Vibration: antisymmetric stretching |

where are positive coefficients.

To determine the coefficients, we note that orthogonal vectors are linearly independent. If we let and solve for

, a possible set of orthogonal SALC vectors are:

| SALC | |

which can further be normalised to give orthonormal SALC vectors.

The method that we have used so far does not take into account the absolute masses of the atoms, only that mass of is different from mass of

. Furthermore, the restriction of motion due to the presence and stiffness of chemical bonds is also not considered. Therefore, the centre of mass does not correspond to the actual centre of mass of the water molecule. It is along the

-axis but not beyond a line joining the centres of the hydrogen atoms. The exact position of the centre of mass of the water molecule affects the values of the coefficients of the SALC vectors, but is inconsequential when the objective is determine which irreducible representation a particular degree of freedom belongs to.

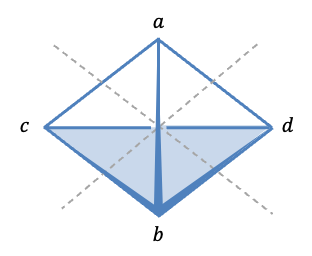

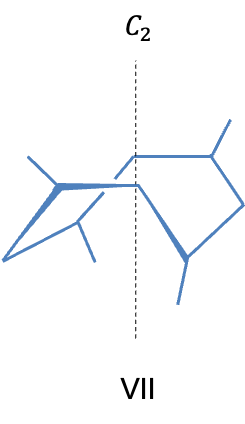

Question

Determine the symmetries of the vibrational modes of .

Answer

There are a total of 12 degrees of freedom. Using a basis set of 3 orthogonal displacement vectors on each atom, we have

which decomposes to .

Deducting the irreducible representations in the character table for translational and rotational motion, the symmetries of the 6 vibrational modes of

are

,

,

and

.

Next article: GRoup theory and infra-red spectroscopy

Previous article: Degrees of freedom

Content page of group theory

Content page of advanced chemistry

Main content page