A composite system is one that has more than one part; for instance, a system of two spin- particles. One possible way to denote a basis set for the eigenstates of the two spin-

particles system is:

or in terms of the -component of the spins:

where the 1st term and 2nd term in the each basis state refer to the -component spin states of the 1st particle and that of the 2nd particle, respectively.

The full notation of is

, which can be condensed to

, or simply

.

To represent the 4 kets in column vector form, we borrow the notation of basis vectors that are used to derive the Pauli matrices and give the kets the following assignments:

If you’ve read the article on Kronecker product, you’ll realise that

Therefore,

Eq194 is called the uncoupled representation of the state of the system. The general state of the system, which is called the coupled representation, is a linear combination of the four basis states:

where ,

,

and

are constants called Clebsch-Gordan coefficients.

Eq195 is often written in the general form:

Question

Why is eq194 the uncoupled representation, while eq195 is the coupled representation? Why is ?

Answer

The -component of the spins in the basis vectors

and

that form the state

in eq194 are assumed to behave independently (non-interacting), whereas the state

in eq195 takes into account the coupled interactions of the spins. For example, the coupled representation is used for the singlet and triplet states (interacting spins), while both the coupled and uncoupled representations are utilised in deriving atomic term symbols where spin-orbit coupling is neglected.

In terms of , see the derivation of eq207 for explanation.

Consider the Hilbert spaces and

that are spanned by the basis states

and

respectively. The Hilbert space of the composite system of the two spin-

particles is the Kronecker product of

and

, i.e.

. To construct a total spin angular momentum operator for

, we have to consider the following:-

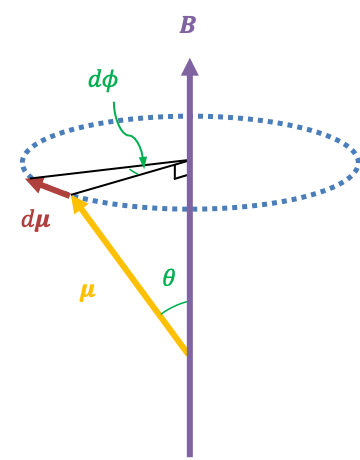

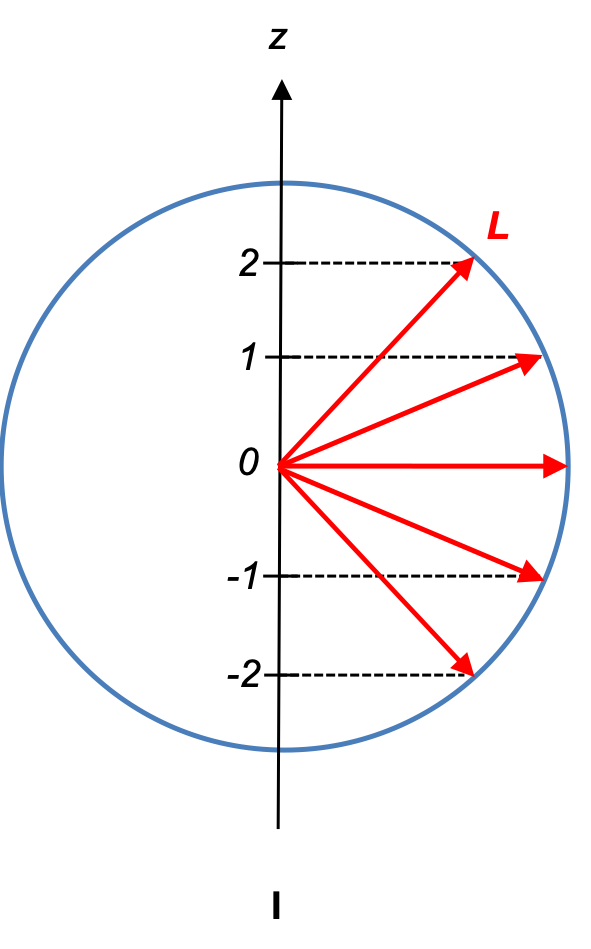

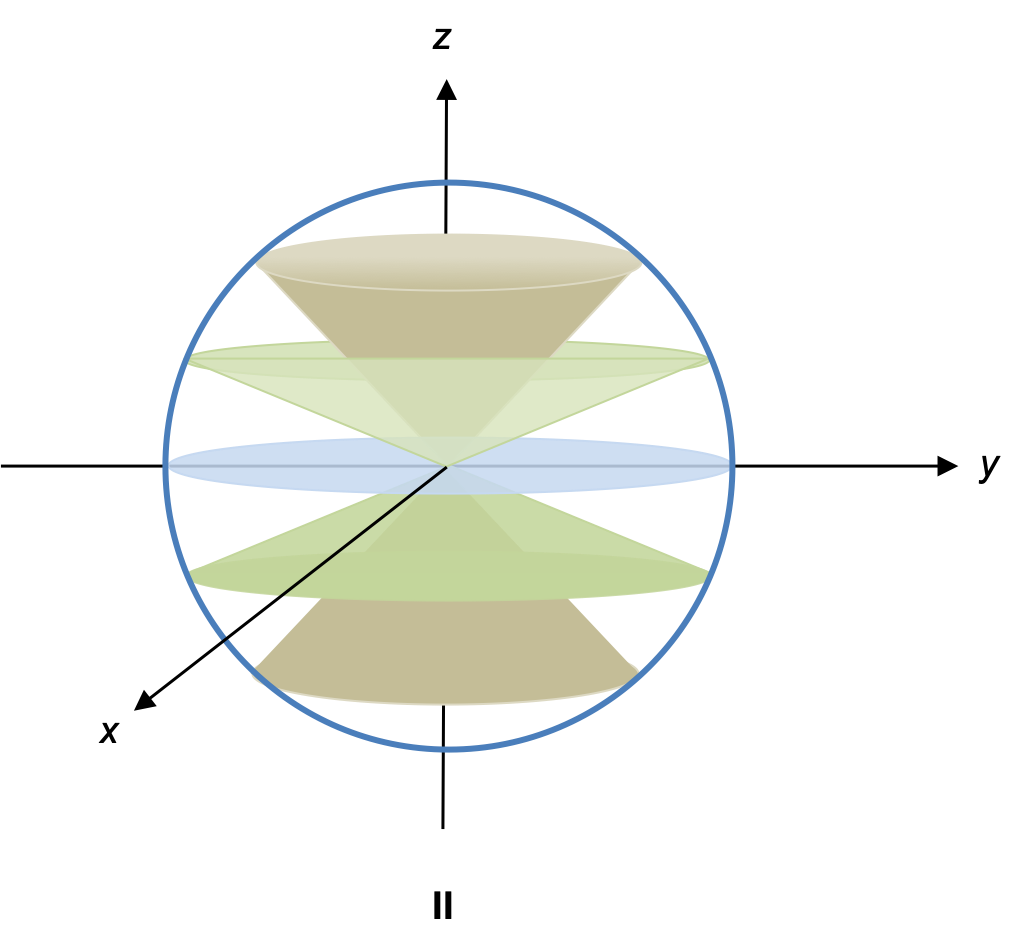

- According to the principle of the conservation of angular momentum of a system, the total

-component of the orbital angular momentum of a system is the sum of all

-components of the orbital angular momentum of particles constituting the system

. The total

-component of spin angular momentum, which is also a form of angular momentum, is postulated to be the sum of all

-components of the spin angular momentum of particles constituting the system

.

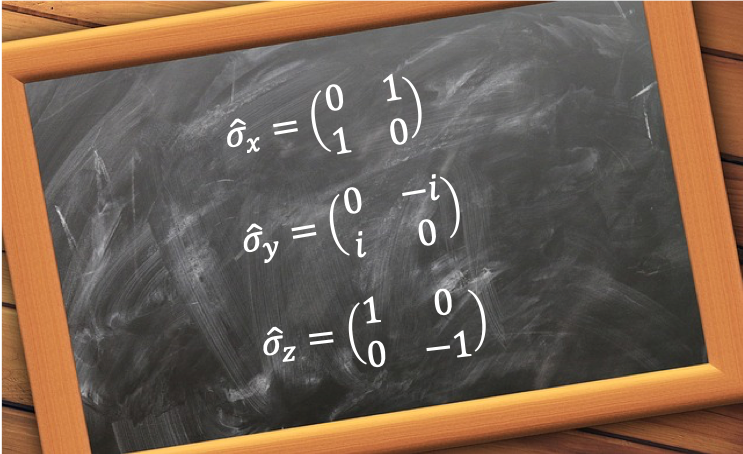

- The spin operator

that acts on eigenstates in the Hilbert space

, and the spin operator

that acts on eigenstates in the Hilbert space

, are 2×2 matrices.

- The eigenvectors in

are column vectors with 4 elements, and hence, the spin operator must be a 4×4 matrix.

Taking the above points in consideration, and

acting on

in the Hilbert space

are defined as:

and

respectively, where is the 2×2 identity matrix.

The total -component spin angular momentum operator

that acts on the eigenstates in the Hilbert space

is therefore:

Substituting eq174 into the above equation,

Similarly, from eq177

and from eq178

Next, we shall derive the matrix for . With regard to eq196, since

,

is equivalent to

. Therefore,

Substitute eq173 and eq179 in eq201,

Substitute eq180 in the above equation and simplifying,

Question

What is the formula for that acts on the eigenstates in the Hilbert space

?

Answer

Question

Show that commutes with

.

Answer

Using eq196 and eq201 in simple notation, . Expanding RHS of this equation and considering the following:

- Use eq179 to find expressions for

,

and

.

and

, where

, act on different vector spaces and hence they commute with each other.

and

.

- Making use of eq165, eq166 and eq167.

We have