The determinant is a number associated with an  matrix

matrix  . It is defined as

. It is defined as

where

-

is an element of in the first row of

is an element of in the first row of  .

.^{1+j}M_{1j}^A) is the cofactor associated with

is the cofactor associated with  .

. , the minor of the element

, the minor of the element  , is the determinant of the

, is the determinant of the  matrix obtained by removing the

matrix obtained by removing the  row and

row and  -th column of

-th column of  .

.

In the case of  , we say that the summation is a cofactor expansion along row 1. For example, the determinant of

, we say that the summation is a cofactor expansion along row 1. For example, the determinant of  is

is

For any square matrix, the cofactor expansion along any row and any column results in the same determinant, i.e.

To prove this, we begin with the proof that the cofactor expansion along any row results in the same determinant, i.e. ^{i+j}M_{ij}^A) for

for  . Consider a matrix

. Consider a matrix  , which is obtained from

, which is obtained from  by swapping row

by swapping row  consecutively with rows above it

consecutively with rows above it  times until it resides in row 1. According to property 8 (see below), we have

times until it resides in row 1. According to property 8 (see below), we have

^{i-1}\vert B\vert=(-1)^{i-1}\sum_{j=1}^nb_{1j}(-1)^{1+j}M_{1j}^B\\=(-1)^{i-1}\sum_{j=1}^na_{ij}(-1)^{1+j}M_{ij}^A=\sum_{j=1}^na_{ij}(-1)^{i+j}M_{ij}^A)

According to property 10,  and therefore, the cofactor expansion along any column also results in the same determinant. This concludes the proof.

and therefore, the cofactor expansion along any column also results in the same determinant. This concludes the proof.

In short, to calculate the determinant of an  matrix, we can carry out the cofactor expansion along any row or column. If we expand along a row, we have

matrix, we can carry out the cofactor expansion along any row or column. If we expand along a row, we have  . We then select any row

. We then select any row  to execute the summation. Conversely, if we expand along a column, we get

to execute the summation. Conversely, if we expand along a column, we get  .

.

The following are some useful properties of determinants:

-

, where is

, where is  the identity matrix. If one of the diagonal elements of

the identity matrix. If one of the diagonal elements of  is

is  , then

, then  .

.

- If the elements of one of the columns of

are all zero,

are all zero,  .

.

- If

is obtained from

is obtained from  by multiplying the

by multiplying the  -th row of

-th row of  by

by  ,

,  .

.

- If

is obtained from

is obtained from  by swapping two rows or columns of

by swapping two rows or columns of  , then

, then

- If two rows or two columns of

are the same,

are the same,  .

.

- The inverse of a matrix exists only if

.

.

- If

, then

, then  .

.

- If

, then

, then  . If

. If  , then

, then  .

.

- If

is diagonal, then

is diagonal, then  .

.

Proof of property 1

We shall proof this property by induction.

For  ,

,

For  ,

,

(-1)^2M_{11}+(0)(-1)^3M_{12}=(1)(-1)^2(1)=1)

Let’s assume that for  ,

,  . Then for

. Then for  ,

,

I_{1n}+1=1)

We can repeat the above induction logic to prove that  if one of the diagonal elements of

if one of the diagonal elements of  is

is  .

.

Proof of property 2

Again, we shall proof this property by induction.

For  ,

,

For  ,

,

(-1)^2M_{11}+c(0)(-1)^3M_{12}=c\vert ci_{22}\vert=c(c)=c^2)

Let’s assume that for  , we have

, we have  . Then for

. Then for  ,

,

I_{11}+c(0)I_{12}+\cdots+c(0)I_{1n}=cI_{11}=c\vert cI\vert_{n-1}=cc^{n-1}=c^n)

Proof of property 3

For  , where

, where  , we have

, we have  . For

. For  , the definition

, the definition  allows us to sum by row or by column. Suppose we sum by row, we have

allows us to sum by row or by column. Suppose we sum by row, we have  . Since we are allowed to choose any column

. Since we are allowed to choose any column  to execute the summation, we can always select the column

to execute the summation, we can always select the column  such that

such that  . Therefore,

. Therefore,  if the elements of one of the columns of are all zero.

if the elements of one of the columns of are all zero.

Proof of property 4

Let’s suppose  is obtained from

is obtained from  by multiplying the

by multiplying the  -th row of

-th row of  by

by  . If we expand

. If we expand  and

and  along row

along row  , cofactor

, cofactor  is equal to cofactor

is equal to cofactor  . Therefore,

. Therefore,

Proof of property 5

For a type I elementary matrix,  transforms

transforms  by swapping two rows of

by swapping two rows of  . So,

. So,  due to property 8. Since

due to property 8. Since  is obtained from

is obtained from  by swapping two rows of

by swapping two rows of  , we have

, we have  according to property 1 and property 8, which implies that

according to property 1 and property 8, which implies that  . Therefore,

. Therefore,  .

.

For a type II elementary matrix,  due to property 4 and

due to property 4 and  because of property 1. So,

because of property 1. So,  .

.

For a type III elementary matrix,

A_{pj}=\sum_{j=1}^na_{pj}A_{pj}+k\sum_{j=1}^na_{qj}A_{pj}=\vert A\vert+k\vert B\vert)

is computed by expanding along row

is computed by expanding along row  . The equation

. The equation  means that when

means that when  is computed by expanding along row

is computed by expanding along row  , it has the same cofactor as when

, it has the same cofactor as when  is computed by expanding along row

is computed by expanding along row  . This implies that

. This implies that  . Since the definition of the determinant of

. Since the definition of the determinant of  is

is  , which in our case is equivalent to

, which in our case is equivalent to  , we have

, we have  . Thus

. Thus  , which according to property 9, gives:

, which according to property 9, gives:

Since  ,

,

according to eq5 and property 1.

Comparing eq5 and eq6,  .

.

Proof of property 6

Case 1

If  is singular, where

is singular, where  , then

, then  is also singular according to property 12. So,

is also singular according to property 12. So,  .

.

Case 2

If  is non-singular, it can always be expressed as a product of elementary matrices:

is non-singular, it can always be expressed as a product of elementary matrices:  . So,

. So,

\vert)

Since property 5 states that  ,

,

Similarly, \vert=\vert\varepsilon_1\vert\vert\varepsilon_2\vert\cdots\vert\varepsilon_k\vert) . Substitute this in the above equation,

. Substitute this in the above equation,  .

.

Proof of property 7

Using property 6 and then property 2,

Proof of property 8

We shall proof this property by induction.  is the trivial case, where

is the trivial case, where  is the rank of a square matrix.

is the rank of a square matrix.

For  , let

, let  and

and  , which is obtained from

, which is obtained from  by swapping two adjacent rows. Furthermore, let

by swapping two adjacent rows. Furthermore, let ^{1+j}m_{1j}^A) and

and ^{1+j}m_{1j}^B) . Clearly,

. Clearly,

=-\vert A\vert)

Let’s assume that for  ,

,  when two adjacent rows are swapped. For

when two adjacent rows are swapped. For  , we have:

, we have:

Case 1: Suppose that the first row of  is not swapped when making

is not swapped when making  .

.

^{1+j}M_{1j}^B=\sum_{j=1}^na_{1j}(-1)^{1+j}M_{1j}^B)

is the determinant of a rank

is the determinant of a rank  matrix, which is the same as

matrix, which is the same as  except for two adjacent rows being swapped. Therefore,

except for two adjacent rows being swapped. Therefore,  and

and ^{1+j}M_{1j}^A=-\vert A\vert) .

.

Case 2: If the first two rows of  are swapped when making

are swapped when making  ,

,

We have ^{1+j}M_{1j}^A) and

and ^{1+k}M_{1k}^B=\sum_{k=1}^na_{2k}(-1)^{1+k}M_{1k}^B) . The minors

. The minors  and

and  can be expressed as

can be expressed as

\sum_{k=1}^{j-1}a_{2k}(-1)^{1+k}\vert A_{kj}\vert+\sum_{k=j+1}^na_{2k}(-1)^{k}\vert A_{jk}\vert)

\sum_{j=1}^{k-1}a_{1j}(-1)^{1+j}\vert A_{jk}\vert+\sum_{j=k+1}^na_{1j}(-1)^{j}\vert A_{kj}\vert)

where  is

is  with the first two rows, and the

with the first two rows, and the  -th and

-th and  -th columns removed.

-th columns removed.

Therefore,

^{1+j}\biggr\[(1-\delta_{1j})\sum_{k=1}^{j-1}a_{2k}(-1)^{1+k}\vert A_{kj}\vert+\sum_{k=j+1}^na_{2k}(-1)^{k}\vert A_{jk}\vert\biggr\])

^{1+k}\biggr\[(1-\delta_{1k})\sum_{j=1}^{k-1}a_{1j}(-1)^{1+j}\vert A_{jk}\vert+\sum_{j=k+1}^na_{1j}(-1)^{j}\vert A_{kj}\vert\biggr\])

For any pair of values of  and

and  , where

, where  , the terms in

, the terms in  are

are ^{1+j}\sum_{k=1}^{j-1}a_{2k}(-1)^{1+k}\vert A_{kj}\vert) , which differ from the terms in

, which differ from the terms in  , i.e.

, i.e. ^{1+k}\sum_{j=k+1}^{n}a_{1j}(-1)^{j}\vert A_{kj}\vert) , by a factor of -1. Similarly, for any pair of values of

, by a factor of -1. Similarly, for any pair of values of  and

and  , where

, where  , the terms in

, the terms in  are

are ^{1+j}\sum_{k=j+1}^{n}a_{2k}(-1)^{k}\vert A_{jk}\vert) , which again differ from the terms in

, which again differ from the terms in  , i.e.

, i.e. ^{1+k}\sum_{j=1}^{k-1}a_{1j}(-1)^{1+j}\vert A_{jk}\vert) , by a factor of -1. Since all terms in

, by a factor of -1. Since all terms in  differ from all corresponding terms in

differ from all corresponding terms in  by a factor of -1,

by a factor of -1,  .

.

In general, the swapping of any two rows  and

and  of

of  , where

, where  , is equivalent to the swapping of

, is equivalent to the swapping of -1) adjacent rows of

adjacent rows of  , with each swap changing

, with each swap changing  by a factor of -1. Therefore,

by a factor of -1. Therefore,

^{2(q-p)-1}\vert A\vert=[(-1)^2]^{p-q}(-1)^{-1}\vert A\vert=-\vert A\vert)

Finally, the swapping of any two columns is proven in a similar way.

Proof of property 9

Consider the swapping of two equal rows of  to form

to form  , resulting in

, resulting in  and

and  . However, property 8 states that

. However, property 8 states that  if any two rows of are swapped. Therefore,

if any two rows of are swapped. Therefore,  if two rows of

if two rows of  are equal. The same logic applies to proving

are equal. The same logic applies to proving  if there are two equal columns of

if there are two equal columns of  .

.

Proof of property 10

Case 1:

If  , then

, then  according to property 13. So,

according to property 13. So,  .

.

Case 2:

Let’s first consider elementary matrices  . A type I elementary matrix is symmetrical about its diagonal, while a type II elementary matrix has one diagonal element equal to

. A type I elementary matrix is symmetrical about its diagonal, while a type II elementary matrix has one diagonal element equal to  . Therefore,

. Therefore,  and thus

and thus  for type I or II elementary matrices. A type III elementary matrix is an identity matrix with one of the non-diagonal elements replaced by a constant

for type I or II elementary matrices. A type III elementary matrix is an identity matrix with one of the non-diagonal elements replaced by a constant  . Therefore, if

. Therefore, if  is a type III elementary matrix, then

is a type III elementary matrix, then  is also one. According to eq6,

is also one. According to eq6,  for a type III elementary matrix. Hence,

for a type III elementary matrix. Hence,  for all elementary matrices.

for all elementary matrices.

Next, consider an invertible matrix  , which (as proven in the previous article) can be expressed as

, which (as proven in the previous article) can be expressed as  . Thus,

. Thus, ^T=\varepsilon_k^T\cdots\varepsilon_2^T\varepsilon_1^T) (see Q&A in the proof of property 13). According to property 5,

(see Q&A in the proof of property 13). According to property 5,

and

Therefore,  .

.

Proof of property 11

We have  , or in terms of matrix components:

, or in terms of matrix components:

_{qk}a_{kp}=\delta_{pq}=\frac{\vert A\vert}{\vert A\vert}\delta_{pq}\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;7)

Consider the matrix  that is obtained from the matrix

that is obtained from the matrix  by replacing the

by replacing the  -th column of

-th column of  with the

with the  -th column, i.e.

-th column, i.e.  for

for  and

and  . According to property 9,

. According to property 9,  because

because  has two equal columns. Furthermore, cofactor

has two equal columns. Furthermore, cofactor  is equal to cofactor

is equal to cofactor  for

for  . Therefore,

. Therefore,

When  , the last summation in eq8 becomes

, the last summation in eq8 becomes

Combining eq8 and eq9, we have  , which when substituted in eq7 gives:

, which when substituted in eq7 gives:

_{qk}a_{kp}=\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{A_{kq}}{\vert A\vert}a_{kp})

Therefore, _{qk}=\frac{A_{kq}}{\vert A\vert}) , which implies that the inverse of a matrix is undefined if

, which implies that the inverse of a matrix is undefined if  . In other words, the inverse of a matrix

. In other words, the inverse of a matrix  is undefined if

is undefined if  . We call such a matrix, a singular matrix, and a matrix with an associated inverse, a non-singular matrix.

. We call such a matrix, a singular matrix, and a matrix with an associated inverse, a non-singular matrix.

Proof of property 12

We shall prove by contradiction. According to property 11,  has no inverse if

has no inverse if  . If

. If  has no inverse and

has no inverse and  has an inverse, then

has an inverse, then ^{-1}\]=I) . This implies that

. This implies that  has an inverse

has an inverse  , where

, where ^{-1}) , which contradicts the initial assumption that

, which contradicts the initial assumption that  has no inverse. Therefore, if

has no inverse. Therefore, if  has no inverse, then

has no inverse, then  must also have no inverse.

must also have no inverse.

Proof of property 13

Question

Show that ^T=\cdots C^TB^TA^T) .

.

Answer

^T=B^TA^T) because

because

^T_{ij}=(AB)_{ji}=\sum_{k=1}^na_{jk}b_{ki}=\sum_{k=1}^n(A^T)_{kj}(B^T)_{ik}\\=\sum_{k=1}^n(B^T)_{ik}(A^T)_{kj}=(B^TA^T)_{ij})

^T=C^TB^TA^T) because

because

^T_{ij}=(ABC)_{ji}=\sum_{l=1}^n\sum_{k=1}^na_{jk}b_{kl}c_{li}=\sum_{l=1}^n\sum_{k=1}^n(A^T)_{kj}(B^T)_{lk}(C^T)_{il}\\=\sum_{l=1}^n\sum_{k=1}^n(C^T)_{il}(B^T)_{lk}(A^T)_{kj}=(C^TB^TA^T)_{ij})

which can be extended to ^T=\cdots C^TB^TA^T) .

.

Using the identity in the above Q&A, ^TA^T=(AA^{-1})^T) . If

. If  is invertible, then

is invertible, then ^TA^T=(AA^{-1})^T=I=(A^{-1}A)^T=A^T(A^{-1})^T) . This implies that

. This implies that ^T) is the inverse of

is the inverse of  and therefore that

and therefore that  is invertible if

is invertible if  is invertible.

is invertible.

The last part shall be proven by contradiction. Suppose  is singular and

is singular and  is non-singular, there would be a matrix

is non-singular, there would be a matrix  such that

such that  , Furthermore,

, Furthermore, ^T=AB^T) , which implies that

, which implies that  . This contradicts our initial assumption that

. This contradicts our initial assumption that  is singular. Therefore, if

is singular. Therefore, if  is singular,

is singular,  must also be singular.

must also be singular.

Proof of property 14

We shall proof this property by induction. For  ,

,

Let’s assume that  for

for  . Then for

. Then for  , the cofactor expansion along the first row is

, the cofactor expansion along the first row is

in the form:

,

,

are integers and

,

,

are primitive translation vectors or basis vectors.

, e.g. a rotation by

, maps

to

, where the components of

are again integers. Such an operation is always possible only if all the entries of

are integers.

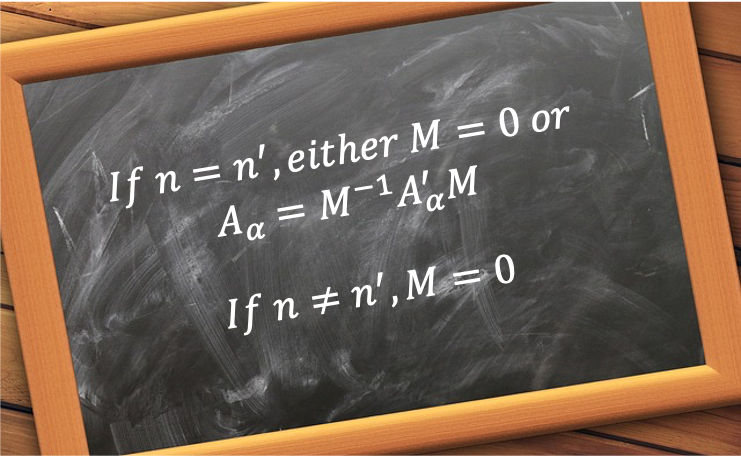

, i.e.

, is also an integer. If we perform a similarity transformation on the rotation matrix

, i.e.

, such that

is with respect to an orthonormal basis for

,

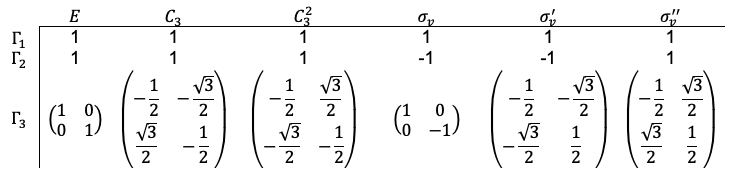

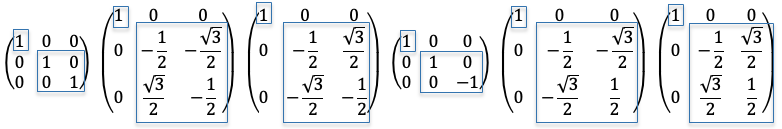

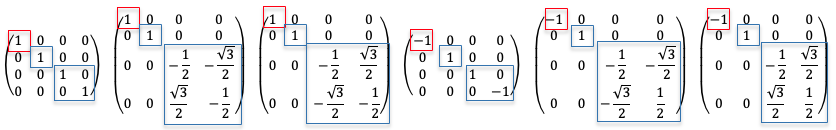

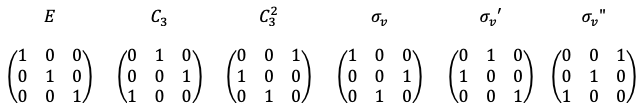

is represented by the following matrices:

is invariant under a similarity transformation,

must also be an integer. As we know,

, and so,

, which implies that

. In other words, the rotational symmetry operations of a crystal are restricted to

. This is known as the crystallographic restriction theorem.

, as it has rotation components. Applying the same logic as above, the entries of the matrix

in the primitive translation vector basis must be integers. An example of the transformed matrix

with respect to an orthonormal basis for

is:

is an integer. We have,

, which allows us to conclude that the

symmetry operations of a crystal are restricted to

.

, we are left with the following 32 crystallographic point groups:

in non-standard orientation

in non-standard orientation

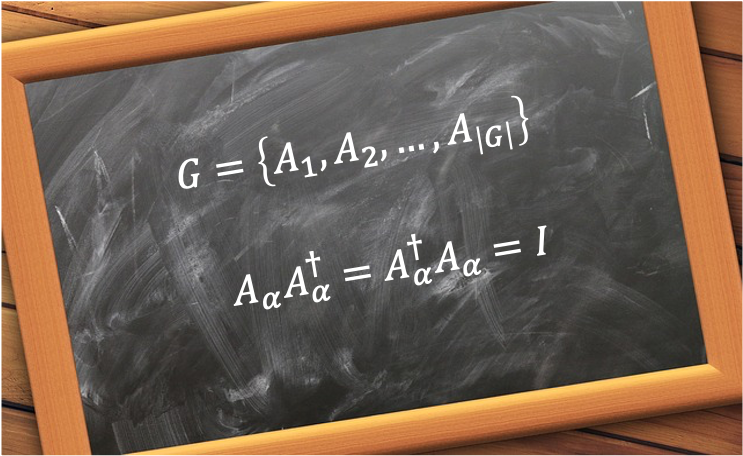

is an element of

is an element of

and

affected by the crystallographic restriction theorem?

and the trace of a mirror plane is an integer, e.g.

.